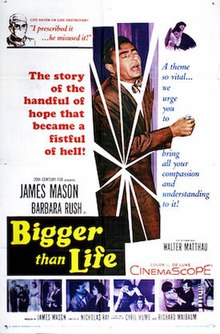

In 1956, just after directing the seminal youth movie Rebel Without a Cause, Nicholas Ray made Bigger Than Life, one his most significant but inexplicably obscure melodramas, perhaps because of its commercial failure upon initial release.

| Bigger Than Life | |

|---|---|

|

|

The movie is based on a nonfiction article, “Ten Feet Tall,” by medical writer Berton Roueche, published in the New Yorker on September 10, 1955. In his piece, he chronicled the life of a schoolteacher from Queens’ Forrest Hill, driven to the brink by negative reaction to Cortisone, then hoped to be and (mis) labeled by the establishment as the “Miracle Drug.”

Roueche wrote: “Mental derangements attributable to cortisone have been reported by hundreds of clinicians. In many cases, these disturbances simulate with absolute fidelity the syndromes classically characteristic of paranoia, schizophrenia, and manic-depressive psychosis.”

Sadly, a critical and commercial failure in its first engagement, Bigger Than Life is not available on video or DVD format in the U.S. The movie has stayed in circulation due to occasional showings on various TV Movie Channels (I caught it recently on TCM), even though it should be seen on the big screen due to its splendid mise-en-scene and striking cinematography. A new 35mm CinemaScope print played with great success at New York’s Film Forum last January.

The screenplay is credited to Cyril Hume and Richard Maibaum, with major (unacknowledged) contributions from Clifford Odets (“The Sweet Smell of Success”) and Gavin Lambert (“Inside Daisy Glover”). The movie transposes the setting of the article from New York to any suburb in the USA, changing the name of the prtotag from Robert Laurence to Ed Avery.

When first met, Avery (James Mason, in brilliant form) comes across as a warm, likable high-school teacher and a sensitive husband and father to a young boy who adores him.

Afflicted with sudden, crippling pains, he’s diagnosed with a rare inflammation of the arteries, and the doctors prescribe cortisone. The tale implies that even before he becomes ill, Avery might have been suffering from spiritual malaise, disenchantment with the typical suburban life of the 1950s. Avery lies to his middle-class, utterly bourgeois wife (Barbara Rush) about his comings and goings; specifically, he conceals the fact that his income comes from an extra job as a taxi dispatcher.

Once Avery falls ill, he begins to pop prescription hormones, first according to doctors’ orders and then exceedingly so. Initially, he reacts well, even rides a euphoric high, rising to (as the story says) “ten feet tall.” He takes the family out to dinners, buys elegant dresses for his wife, and showers them with expensive gifts they were never able to afford.

However, once addicted, he begins to exhibit strange behavior, first excessive energy and enthusiasm, then by making new demands on his family, a snobbish, dictatorial attitude toward his students, feelings of megalomania, and irrational and spontaneous outbursts of anger.

Among many side effects, Avery’s addiction brings to the surface his unconscious or subconscious anxieties, which reflect the zeitgeist of ultra-conservative and conformist post-WWII American society. This becomes very clear, when he charges at his wife, “Everybody’s Dull. We’re Dull,” when she complaints about a soiree that did not go so well. Moreover, at a PTA meeting, speaking his mind openly, Avery offends teachers and parents with a speech about “breeding a race of moron midgets,” announcing plans to write a “life work” manuscript that will teach people how to make themselves over in his own image.

In a long monologue, Avery’s wife relates to his colleague and family friend (played by the young Walter Matthau) his (and director Ray’s) contempt for the banal mediocrity of American TV: “He gave a howl that almost froze my blood. No wonder we couldn’t keep pace with him. No wonder we couldn’t give him the sympathy and understanding he needed. No wonder he was all-alone. He let out another yell and dived across the room and shut the program off. Then he backed away a step and doubled up his fist. Maybe this would bring us to our senses. He’d show us what he thought of television. He was going to take his fist and smash that screen to bits.”

Contextually, the New Yorker article was published in 1955, the same era in which the Sam Mendes’ recent suburban anatomy, “Revolutionary Road,” takes place, which is based on Richard Yates’ 1960 novel. It’s also the year in which Hollywood made another film about addiction, albeit a more mainstream and soothing than this one, Otto Preminger’s “The Man With the Golden Arm,” starring Frank Sinatra, which was controversial but also a huge success. It’s noteworthy that Douglas Sirk’s critiques of bourgeois American life, “All That Heaven Allows” and “Written on the Wind,” appeared in 1955 and 1956, respectively.

Perfectly cast, James Mason, who’s also credited as producer, combines in his portrait alert intellect, rational sensibility, emotional intensity, real menace, and inexplicable rage, the same qualities he had brought the year before to George Cukor’s remake of “A Star Is Born” (1954), as the alcoholic husband in decline opposite Judy Garland.

Shooting in wide-screen with lurid bright colors (the bottle of cortisone pills glows in purple), cinematographer Joseph MacDonald emphasizes Ray’s ominous imagery, with its sharp low-angle or high-angle shots, borrowing from the vocabulary of film noir. Note the huge shadow of Avery, reflected against the wall, while leaning over his son at his desk demanding discipline. (His mother sneaks food and a glass of milk when the father is not watching)

An outsider filmmaker operating on the fringes of mainstream Hollywood, with a history of addictions himself, Ray is clearly more sympathetic to Avery than to his family or doctors—his criticism of the American Way of Life is evident in most of his work. Against Ray’s wishes, a happier, more soothing resolution was imposed on the picture by the Production Code, but it can’t really conceal the emotional tensions and ideological cracks that run through the narrative.

Cast

James Mason as Ed Avery

Barbara Rush as Lou Avery

Walter Matthau as Wally Gibbs

Robert F. Simon as Dr. Norton

Russell Quick as Bully

Christopher Olsen as Richie Avery

Roland Winters as Dr. Ruric

Rusty Lane as Bob LaPorte

Rachel Stephens as Nurse

Kipp Hamilton as Pat Wade

Credits:

Directed by Nicholas Ray

Screenplay by Cyril Hume, Richard Maibaum, based on “Ten Feet Tall” by Berton Roueché

Produced by James Mason

Cinematography Joseph MacDonald

Edited by Louis R. Loeffler

Music by David Raksin

Distributed by 20th Century Fox

Release date: August 2, 1956

Running time: 95 minutes

Budget: $1 million