Set against India’s shifting political contexts, George Cukor’s tragic political melodrama, Bhowani Junction is one of his few grand on-location productions. The exteriors of the picture were shot in Pakistan’s Lahore, and the interiors at London’s Elstree studio.

Our Grade: B (*** out of *****)

Ava Gardner, then MGM’s most popular star, plays Victoria, an Anglo-Indian woman who has affairs with three men: Patrick, a young Anglo-Indian (Bill Travers); Ranjit, an Indian prince (Francis Matthews) who wants to marry her; and Savage, a British Colonel (Stuart Granger). Cukor’s portrait emphasizes the genuinely moving and tragic elements of his heroine’s life; she’s a woman deemed immoral, or at least promiscuous by society.

In January 1955, a rough draft of the screenplay for “Bhowani Junction” was submitted for the approval of the PCA. The censors complained there was too much emphasis on Victoria in girdle, bra, and panties, and not enough on her conflicted persona. They also reminded that the love scenes could not be played with the couple in a prone position. Hence, the censors asked for rewrites of Victoria’s description of her attempted rape to stress the rapist’s insanity and homicidal intent rather than its sexual contents. Even a line like, “I jabbed him hard with my elbow, he moaned and bent forward,” was considered too suggestive (of a blow to the groin).

The vet British John Mills was disappointed when Cukor informed him that the role of Patrick had already been cast. Cukor was disappointed too, because Mills would have been a wonderful Patrick, but the part had been offered to another Britisher, Bill Travers. MGM was excited about Travers, hoping he would become an international star; he did not.

Due to time pressures, Sonya and Ivan Moffat were forced to write the script out of continuity. The scribes first worked on the outdoor sequences, then, once the pressures eased, they wrote the more intimate scenes. This was not the most satisfactory method of preparing a script, but there was no choice, as the budget was escalating.

Cukor sent the working script to John Masters “under the table,” strictly on his own, for some necessary corrections. He knew of no better way of capturing the book’s quality other than taking advantage of the advice of the author himself. For some mysterious reason, it was considered heresy in Hollywood to have anything to do with the author of the original work. But Cukor disliked the initial script since it managed to trivialize and conventionalize the characters and also missed the book’s humor.

On “Bhowani Junction,” Cukor worked for the second time with cinematographer Freddie Young, for whom he had the highest regard, recalling happy times on the set of their first effort, the 1949 melodrama, Edward, My Son. Young was given complete control of visual imagery–Cukor had assured him that his art consultant and friend George Huene would not encroach on his work.

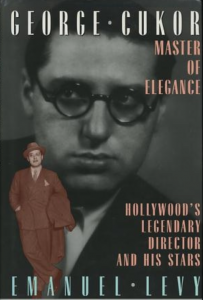

Please read my biography of Cukor:

Ever since the debacle of Gone With the Wind, Cukor had been waiting for the opportunity to show David O. Selznick (who had fired him from that film), and his other critics, that he could handle an epic spectacle, an outdoor film with plenty of action, crowd scenes, and thousands of extras.

Unfortunately, the Indian press and film industry were against the production from the start. The Indian government refused to grant permission to shoot in India, basing their objection on one line in the script that described Indian politicians in a disparaging way. Afraid that this procrastination could continue indefinitely, producer Pandro Berman switched the movie to Pakistan.

Perceiving India as the film’s lead character, for the first time in his career, Cukor devoted a lot of time to the look of the production. The on-location shooting contributed to the film’s authenticity. Using the dominant color of a brownish tone, Cukor hoped it would make the audience see the country in a new, if also unsettling light. Cukor became quickly aware of the unexpected, often contradictory sights around. On the one hand, he saw exposed electric wires and utter poverty, but on the other, there was the grandeur of a great palace like the Taj Mahal.

A strenuous picture, due to many films, it took a great deal of effort to execute. But ultimately Bhowani Junction contains impressive sequences that are unique in Cukor’s work, such as the verisimilitude of the Indian atmosphere, the staging of crowd scenes, people caught up in social upheaval, the whole way in which Cukor convey a restless country on the move. The film reflects Cukor’s impression of India at the time as a country, which he later described as “thousands of people swarming around. People, people, people!” An unfamiliar sight from the controlled atmosphere of the MGM soound stages, as well as the clean and lavish look of his residence in the posh area of the Hollywood Hills.

In the scene where the passive resisters lie down in front of the train, Cukor show in detail how the army was ruthlessly pissing and pouring buckets of shit over the protestors. He later said that he saw much that regrettably he couldn’t use on screen, due to the studio’s sanitizing approach based on fear of censorship, and of India’s diplomats’ reaction to the movie.

Bhowani Junction was also one of the few films in Cukor’s career in which he was defeated by the casting. In the past, he was always in complete control of his ensembles–he considered casting as his greatest specialties and strengths. But in this picture, Stewart Granger had been selected before Cukor was signed as director. Cukor felt that Granger was miscast, and worse, that in his scenes with Ava Gardner, he brought out the movie queen out of her. Gardner also did not like much Granger and his stiff delivery and pompous attitude, They both felt that she would have been better with an actor like Trevor Howard, who was Cukor’s first choice.

Despite the frustrations of this production, for Cukor, the major reward was creating a climate where Ava Gardner rendered one of her very best work to date, giving a “full-bodied and original” performance. The more he saw Gardner’s work, the more depth, dignity and feeling he found in it. Bhowani Junction was in many ways a worthy companion piece to Mogambo, John Ford’s 1953 on-location (Africa) epic, which starred Gable and Ava Gardner in a role that earned her her first and only Best Actress nomination.

As noted, due to censorship, Gardner was discreetly dressed, and very careful with the cleavages of her dresses–to the point of measuring inches and half inches of what was revealed. But Gardner was the kind of actress who exuded sex appeal effortlessly–Cukor said Ava could think “untrammeled things” and the audience would understand it, without her uttering one word of dialogue, just by looking at her eyes or body gestures. There was always a kind of “unexplainable” electricity when Gardner came on the screen, which went beyond her dazzling beauty and photogenic look.

During postproduction, novelist John Masters kept reminding Cukor that he hadn’t gone to Pakistan to make a “large and commercial” Hollywood picture, but to turn his book into a “real and gritty story.” Masters therefore advised to maintain the strong underlying more intimate sexual tension, whenever possible. Hence, when people talk under the shadow of a platform, the glare of the sun should be seen as if hurting badly their eyes. Under Masters’ guidance, Cukor noticed that in India, most people do not stand still; they shift constantly and uncomfortably.

To Cukor’s disappointment, the preview audiences indicated disappointment with the film. They seemed unsympathetic to Victoria’s tragic tale, and MGM forced him to change the focus of “Bhowani Junction” into the colonel’s story. As a result, the picture had to be rearranged, setting the story in flashback, with Granger’s colonel’s voice-over narration. Never mind that his narration contained a lot of unnecessary exposition and created further distance between the viewers and the screen.

In the end, “Bhowani Junction” was turned into a compromisingly sentimental love story, depicting an unsatisfying resolution of a romantic union between Gardner and British officer Granger.

For Cukor, who invested a lot of energy into the movie, Bhowani Junction was an artistic failure, feature that fell in between its two narrative strands: shallow as a tragic portrait of a woman’s divided and troubled identity, and oversimplified as a political melodrama, set against tumultuous political circumstances.

But the movie proved very commercially successful, due to Ava Garner’s popularity, especially in Europe (in France, it was one of the ten most watched pictures with over 1.55 million admissions).

Bhowani Junction earned $2,07 million in America and $2.8 million elsewhere, generating a profit of $1.2 million for MGM.

Cast

Ava Gardner as Victoria Jones

Stewart Granger as Colonel Rodney Savage

Bill Travers as Patrick Taylor

Abraham Sofaer as Surabhai

Francis Matthews as Ranjit Kasel

Marne Maitland as Govindaswami

Peter Illing as Ghan Shyam aka Davay

Edward Chapman as Thomas Jones

Freda Jackson as the Sadani

Lionel Jeffries as Captain Graham McDaniel

Alan Tilvern as Ted Dunphy

Yousaf D Hamdani as Assistant Director

Neelo as a 15-year-old girl

Zohra Mahmood, special appearance