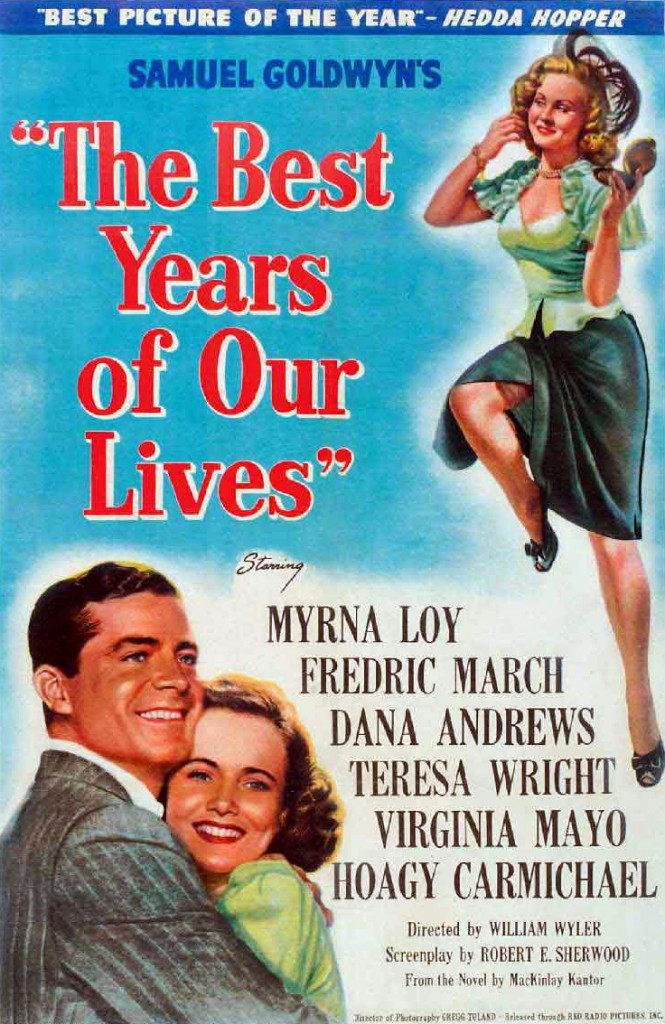

William Wyler’s The Best Years of Our Lives, the most honored film of 1946, received the largest number of awards to date, seven legitimate and two Special Oscars.

Our Grade: A (***** out of *****)

A timely social drama, as if torn of off newspapers headlines, “Best Years of Our Lives” captured the mood of post-WWII America so effectively that even the harsher critics failed to recognize its flaws. Independent producer Samuel Goldwyn, who released the film through RKO, was inspired by an August 7, 1944 article in Time magazine, which recounted the homecoming story of war veterans.

“I don’t care if it doesn’t make a nickel, the colorful producer Sam Goldwyn had famously said, “I just want every man, woman, and child in america to see it.”

Goldwyn commissioned MacKinlay Kantor to write a screenplay, which was first published as a book, “Glory for Me,” then adapted to the screen by Robert Sherwood. Released on November 21, 1946, “Best Years” was relevant and timely, as many Americans were still struggling with painful readjustment to civilian life after the War.

Goldwyn commissioned MacKinlay Kantor to write a screenplay, which was first published as a book, “Glory for Me,” then adapted to the screen by Robert Sherwood. Released on November 21, 1946, “Best Years” was relevant and timely, as many Americans were still struggling with painful readjustment to civilian life after the War.

In his rave review, the film critic James Agee thought that “Best Years” was “profoundly pleasing, moving and encouraging.” Agee singled out its script, which was “well differentiated, efficient, free of tricks of snap and punch and over-design,” and its visual style, which was of “great force, simplicity and beauty.” Agee found William Wyler’s direction to be “of great purity, directness and warmth, about as cleanly devoid of mannerisms, haste, superfluous motion, aesthetic or emotional over-reaching.”

The movie was photographed by Gregg Toland in black and white, with long shots, deep focus, which allowed viewers to see clearly the foreground and background at the same time, and crisp imagery, especially in the two-shots and close-ups.

The acting was also superb, particularly by Fredric March, who won a second Best Actor for playing an anguished banking executive and ex-sergeant, who realizes that in his absence his family–and the larger society–have irrevocably changed.

The tale centers on three servicemen, Al Stephenson (March), Fred Derry (Dana Andrews), and Homer Parris (Harold Russell), who return to their hometown. All three, despite variability in social class and position, are united by one thing: They are still haunted by memories of the War and doubts about their future as civilians.

The tale centers on three servicemen, Al Stephenson (March), Fred Derry (Dana Andrews), and Homer Parris (Harold Russell), who return to their hometown. All three, despite variability in social class and position, are united by one thing: They are still haunted by memories of the War and doubts about their future as civilians.

The most touching story is that of the sailor Homer, who comes home to his girl Wilma (Cathy O’Donnell) with a pair of hooks instead of hands. Homer was played by Russell, the only nonprofessional in the cast, who lost his hands in training accident while in the service.

Middle-aged Al returns to his old banker job and his loving wife Milly (Myrna Loy) and children, one of whom is played by Teresa Wright, as the sensitive Peggy.

The most cynical subplot concerns Fred, who realizes that in his absence his spouse, Marie Derry (Virginia Mayo), has abandoned him and that he has few career prospects.

“I don’t care if the film doesn’t make a nickel,” Goldwyn is supposed to have said, “I just want every man, woman, and child in America to see it.” Goldwyn’s colleagues thought he would lose his shirt, but “Bet Years” proved to be a smash box-office hit.

“Best Years of Our Lives” won the Best Picture Oscar over the British Shakespearean adaptation, “Henry V,” starring Olivier; Frank Capra’s spiritual small-town saga, “It’s a Wonderful Life,” with Jimmy Stewart; the stuffy adaptation of Somerset Maugham’s “The Razor’s Edge,” with a miscast Tyrone Power; and the old-fashioned Americana, “The Yearling,” with Gregory Peck and Jane Wyman.

“Best Years of Our Lives” won the Best Picture Oscar over the British Shakespearean adaptation, “Henry V,” starring Olivier; Frank Capra’s spiritual small-town saga, “It’s a Wonderful Life,” with Jimmy Stewart; the stuffy adaptation of Somerset Maugham’s “The Razor’s Edge,” with a miscast Tyrone Power; and the old-fashioned Americana, “The Yearling,” with Gregory Peck and Jane Wyman.

Detailed Plot

Three guys, Fred Derry (Andrews), Homer Parrish (Russell), and Al Stephenson (March) meet randomly, while waiting for their flight back home to Boone City (a fictional city. modeled after Cincinnati).

Fred was a decorated Army Air Forces captain and bombardier in Europe. Homer lost both hands when his aircraft carrier sunk, and now uses hooks. Al served as an infantry platoon sergeant in the Pacific.

Fred was a decorated Army Air Forces captain and bombardier in Europe. Homer lost both hands when his aircraft carrier sunk, and now uses hooks. Al served as an infantry platoon sergeant in the Pacific.

Al has a comfortable home and loving family: wife Milly (Myrna Loy), daughter Peggy (Teresa Wright), and college freshman son Rob (Michael Hall). He returns to his old job as a bank loan officer. The bank president views his military experience as valuable in dealing with veterans. When Al approves a loan (without collateral) to a young Navy veteran, however, the president expresses reservations. Later, at a banquet in his honor, Al claims that the bank must stand with the vets who risked everything to defend the country and give them every chance to rebuild their lives.

Fred had been an unskilled drugstore soda jerk, and now wants something better, but the postwar market forces him to return to his old job. Fred had met and married Marie (Virginia Mayo) shortly before leaving for the War. In his absence, she became a night club waitress and now has expectations for a better life.

Fred had been an unskilled drugstore soda jerk, and now wants something better, but the postwar market forces him to return to his old job. Fred had met and married Marie (Virginia Mayo) shortly before leaving for the War. In his absence, she became a night club waitress and now has expectations for a better life.

Homer was a football quarterback and became engaged to Wilma (Cathy O’Donnell) before joining the Navy. But now he does not want to burden Wilma with his handicap and tries to push her away, though she still is committed to marrying him.

Peggy meets Fred while bringing her father home from a bar where the three men meet and drink. Peggy informs her parents she intends to end Fred and Marie’s marriage. Concerned, Al demands that Fred stop seeing his daughter, and the friendship between the two is strained.

At the drugstore, an obnoxious customer who claims the War was fought against wrong enemies, gets into a fight with Homer. Fred intervenes and knocks the man into a glass counter, costing him his job. Fred encourages Homer to put his misgivings behind him and marry Wilma. Homer demonstrates to Wilma how hard life with him would be, but she remains undaunted.

At the drugstore, an obnoxious customer who claims the War was fought against wrong enemies, gets into a fight with Homer. Fred intervenes and knocks the man into a glass counter, costing him his job. Fred encourages Homer to put his misgivings behind him and marry Wilma. Homer demonstrates to Wilma how hard life with him would be, but she remains undaunted.

Fred discovers his wife cheating with another vet, and Marie complains that she has “given up the best years of my life,” for him and wants to divorce. Fred decides to leave town, and gives his father his medals and citations for his Distinguished Flying Cross as composed by General Doolittle. At the airport, Fred books the first outbound aircraft, without regard for the destination. While waiting, he wanders into a vast aircraft boneyard and relives the intense memories of combat. When the boss says the aircraft aluminum is being salvaged for building houses, Fred asks him for a job.

Homer and Wilma’s wedding takes place in the Parrish home, with the now-divorced Fred as Homer’s best man. Fred and Peggy watch each other from across the room, exchange smiles, and then embrace, heading into an unknown future.

Commercial Appeal:

Made on a budget of $3 million, the movie was a huge commercial hit, earning $24 million at the box-office.

Over the years, the stature and appeal of the film have been elevated due to repeated showings on TV, especially during Vet Day. And though William Wyler had made many good movies (Ben-Hur in 1959), The Best Years of Our Lives is arguably his most emotionally heartfelt and most fully realized picture.

Looking Back:

Best Years of Our Lives was a new type of film, an intimate tale done on a massive scale, fearlessly examining the ideological cracks in the American value system in the late 1940s. There’s no longer the belief that veterans would be treated honorably when they return, that the economy would perform miracles, that marriages would last, no matter what obstacles (absence of the husband for years). There are no longer clear villains and heroes.

The movie exposed problems–both in the public and the private domains–in a sensitive and subtle way, indicating a new direction and the sense that history is being made right in front of our eyes.

The scope of the film is epic, based on a large ensemble of characters (equally balanced along gender lines), and only two characters that are schematically constructed.

Of the women, only Virginia Mayo’s erring wife, Marie is narrowly viewed and judged. She is portrayed as an easy-going slut, dating men while her husband serves in the war. The movie never takes her side: How did she survive all those years, both financially, emotionally, and sexually. If the movie has a villainous figure, it’s Marie; no attempt is made to humanize her.

Cast

Myrna Loy as Milly Stephenson

Fredric March as Platoon Sergeant Al Stephenso

Dana Andrews as Captain Fred Derr

Teresa Wright as Peggy Stephenso

Virginia Mayo as Marie Derr

Cathy O’Donnell as Wilma Camero

Hoagy Carmichael as Uncle Butch Engle

Harold Russell as Petty Officer Homer Parris

Gladys George as Hortense Derr

Roman Bohnen as Pat Derr

Ray Collins as Mr. Milton

Mina Gombell as Mrs. Parris

Walter Baldwin as Mr. Parris

Steve Cochran as Clif

Dorothy Adams as Mrs. Camero

Don Beddoe as Mr. Cameron

Marlene Aames as Luella Parris

Charles Halton as Pre

Ray Teal as Mr. Mollet

Howland Chamberlain as Thorpe

Dean White as Nova

Erskine Sanford as Bullard

Michael Hall as Rob Stephenson

Cameos by Celebs