Dziga Vertov’s motto, circa 1923:

“I an Kino-eye, I am a mechanical eye, I, a machine, show you the world a only I can see it.”

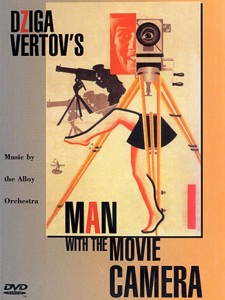

In the 2012 Sight and Sound poll, critics voted Man with a Movie Camera the 8th best film ever made. In 2014, Sight and Sound named the film the best documentary of all time.

Man with a Movie Camera, Dziga Vertov’s feature, whose running time is 69 minutes, presents urban life in the Ukrainian cities of Odessa, Kharkiv, and Kiev. From dawn to dusk Soviet citizens are shown at work and at their leisure, living a new, more modern lifestyle.

It was produced in 1929 as a silent film by the studio VUFKU. The feature, which has no actors or story or sets, is truly experiemental. Its unusual characters are the cameramen, the film editor, and the modern Soviet Union they depict on screen.

This film displays innovative stylistic devices, such as double exposure, fast motion, slow motion, freeze frames, jump cuts, split screens, extreme close-ups, tracking shots, footage played backwards, stop motion animations.

The film uses such scenes as superimposing a shot of a cameraman setting up his camera atop a second camera, superimposing a cameraman inside a beer glass, filming a woman getting out of bed and getting dressed, and a woman giving birth, and the baby taken away to be bathed.

Vertov shot all the scenes separately, with no intention of turning them into a narrative based on a storyline. Instead, he took all the random clips and put it in a database, which Svilova later edited. She examined all the random assemblage of clips that Vertov had shot and then edit it by putting the shots together. Vertov’s purpose was to break the mold of the conventional linear film, which has become the standard for both moviemakers and audiences.

Vertov shot all the scenes separately, with no intention of turning them into a narrative based on a storyline. Instead, he took all the random clips and put it in a database, which Svilova later edited. She examined all the random assemblage of clips that Vertov had shot and then edit it by putting the shots together. Vertov’s purpose was to break the mold of the conventional linear film, which has become the standard for both moviemakers and audiences.

To get footage using a hidden camera, Vertov and his brother Mikhail Kaufman (the film’s co-author) had to distract the subject with something else.

The film also contains the shot of chess pieces being swept to the center of the board (a shot spliced in backwards so the pieces expand outward and stand in position).

Initially, the film was criticized for both the process in which it was made and experimentation involved, a result of its director’s frequent assailing of fiction film as a new “opiate of the masses,” quoting from Marx (who said it about religion).

Initially, the film was criticized for both the process in which it was made and experimentation involved, a result of its director’s frequent assailing of fiction film as a new “opiate of the masses,” quoting from Marx (who said it about religion).

Born David Abelevich Kaufman , Vertov was an early pioneer in documentary filmmaking in the late 1920s. He belonged to a movement known as the kinoks, or kinooki (kino-eyes). Vertov, along with kino artists aimed to abolish all non-documentary styles of film-making.

Most of Vertov’s films were controversial, and the kinok movement was despised by some. Vertov’s crowning achievement, Man with a Movie Camera, was his response to critics who rejected his previous film, A Sixth Part of the World. Critics declared that Vertov’s overuse of “intertitles” was inconsistent with the film-making style the ‘kinoks’ subscribed to.

In anticipation of the film’s release, h requested a warning to be printed in the Soviet central newspaper, Pravda, which spoke of the film’s experimental and controversial nature. Vertov was worried that the film would be either destroyed or ignored by the public. Upon release of Man with a Movie Camera, Vertov issued a statement at the beginning of the film, which read:

“The film Man with a Movie Camera represents

“The film Man with a Movie Camera represents

AN EXPERIMENTATION IN THE CINEMATIC COMMUNICATION

Of visual phenomena

WITHOUT THE USE OF INTERTITLES

(a film without intertitles)

WITHOUT THE HELP OF A SCENARIO

(a film without a scenario)

WITHOUT THE HELP OF THEATRE

(a film without actors, without sets, etc.)

This new experimentation work by Kino-Eye is directed towards the creation of an authentically international absolute language of cinema – ABSOLUTE KINOGRAPHY – on the basis of its complete separation from the language of theatre and literature.”

This manifesto echoes an earlier one Vertov wrote in 1922, in which he disavowed several popular films because they were too indebted to literature and theater.

Because of doubts before screening, and anticipation from Vertov’s pre-screening statements, the film gained great interest before even being shown. And when the film was finally screened, the public either embraced or dismissed his stylistic choices.

Because of doubts before screening, and anticipation from Vertov’s pre-screening statements, the film gained great interest before even being shown. And when the film was finally screened, the public either embraced or dismissed his stylistic choices.

The pace of the film’s editing—more than four times faster than a typical feature, with approximately 1,775 separate shots—disturbed some viewers and mainstream critics.

Man with a Movie Camera’s usage of double exposure and seemingly ‘hidden’ cameras made the movie seem more experimental than linear. Many of the scenes in the film contain people, which change size or appear underneath other objects. The sequences and close-ups capture emotional qualities, which could not be fully portrayed through the use of words.

The film’s lack of typical ‘actors’ and ‘sets’ makes for a unique view of the everyday world, directed toward the creation of a purely cinematic language, distinct from the language of theatre and literature.

The film’s lack of typical ‘actors’ and ‘sets’ makes for a unique view of the everyday world, directed toward the creation of a purely cinematic language, distinct from the language of theatre and literature.

End Note

It is sometimes referred to as The Man with the Movie Camera, The Man with a Camera