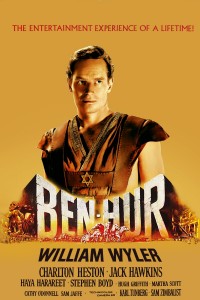

The historical epic Ben-Hur, which won the Best Picture Oscar in 1959, boasted achievements in a number of departments.

The historical epic Ben-Hur, which won the Best Picture Oscar in 1959, boasted achievements in a number of departments.

It was the most expensive film ever made to date, with a budget of $15 million, one fifth of which was allocated for promotion and advertisement.

The film was produced in Rome by Sam Zimablist, who reportedly constructed 3,000 sets and employed over 50,000 people. The highly anticipated movie world-premiered at the Egyptian Theater, on Hollywood Boulevard, on November 24, 1959.

It soon after became a movie event, the most-talked about picture of the year–for a variety of reasons. Every element is big–no, massive– in this production.

Ben-Hur was the first remake to ever win the Best Picture Oscar. MGM was nervous and not only due to the huge budget but also due to the fact that there were viewers who still recalled fondly the 1927 silent epic, starring Ramon Novarro (at his peak) and Francis X. Bushman.

Back in 1959, the picture won the largest number of awards to date: eleven out of its twelve nominations. The only category in which the film lost was screenplay, credited to Karl Tunberg, though at least four distinguished writers contributed to its writing: Maxwell Anderson, S.N. Behrman, Christopher Frye, and Gore Vidal, which might have been the reason for its loss; the well-deserved winner was Neil Paterson for “Room at the Top.”

“Ben-Hur” was the only historical spectacle in the Best Picture contest, up against small, intimate movies, such as Otto Preminger’s “Anatomy of a Murder,” George Stevens’ Holocaust drama “The Diary of Anne Frank,” Fred Zinnemann’s morality tale “The Nun’s Story,” and Jack Clayton’s UK realistic drama “Room at the Top.”

“Ben-Hur” was the only historical spectacle in the Best Picture contest, up against small, intimate movies, such as Otto Preminger’s “Anatomy of a Murder,” George Stevens’ Holocaust drama “The Diary of Anne Frank,” Fred Zinnemann’s morality tale “The Nun’s Story,” and Jack Clayton’s UK realistic drama “Room at the Top.”

Based on Lew Wallace’s popular novel about the rise of Christianity, “Ben-Hur” features spectacular visual effects.

The stunning chariot race, choreographed by Hollywood’s top second unit directors, headed by Yakima Canutt, the genius stunt man who is responsible for the physical movements of John Wayne and who contributed to numerous John Ford Westerns.

Its acting, by contrast, is not spectacular. Charlton Heston lucked out: He was cast after Universal refused to loan out Rock Hudson for the part. Playing the title role of a converted Christian, in conflict with Massala (Stephen Boyd), the Roman commander and his former childhood friend, he gives a decent performance, though a bit stiff in the long dialogue scenes.

But the film’s shortcoming did not matter much, since “Ben-Hur” was marked by a then new visual sweep and enough pageantry to entertain audiences for its epic length, 212 minutes.

As usual, William Wyler directs the story in a tasteful and understated manner, never succumbing to the temptations of making a trashier historic sand and sandals genre item.

Decades later, the chariot race, which occupies about 20 minutes of screen time, is still majestic and spectacular to behold. MGM publicity sent reviewers at the time press releases about the magnitude of the challenge: the size of the colossal arena, the unprecedented number of sets, statues, extras, horses, and tons of sand brought to the sequence, which took no less than three months to shoot.

Decades later, the chariot race, which occupies about 20 minutes of screen time, is still majestic and spectacular to behold. MGM publicity sent reviewers at the time press releases about the magnitude of the challenge: the size of the colossal arena, the unprecedented number of sets, statues, extras, horses, and tons of sand brought to the sequence, which took no less than three months to shoot.

Overcoming MGM’s initial fears, “Ben-Hur” was such an instant commercial success that its grosses were weekly reported to the public to make it seem as “a must-see” movie, which it became, with the assistance of mostly good reviews and word of mouth. Playing for months, the movie grossed over $80 million in worldwide rentals.

Detailed Plot

Judah Ben-Hur (Charlton Heston), a wealthy merchant in Jerusalem living with his mother Miriam (Martha Scott), sister Tirzah (Cathy O’Donnell), is devoted to his faith and the freedom of the Jewish people. Also in residence is their slave Simonides (Sam Jaffe) and his daughter, Esther (Haya Harareet), who loves Ben-Hur but is betrothed to another. Ben-Hur’s childhood friend Messala (Stephen Boyd), is now a tribune returning as the new commander.

During the parade for the new governor of Judea, Valerius Gratus, some loose tiles fall from the roof of Ben-Hur’s house, and Gratus is thrown from his horse and nearly killed. Although Messala knows it was an accident, he condemns Ben-Hur to the galleys and imprisons Miriam and Tirzah. He hopes to intimidate the Jewish populace, but Ben-Hur swears to take revenge.

After three years as a galley slave, Ben-Hur is assigned to Roman Consul Quintus Arrius (Jack Hawkins), charged with destroying the Macedonian pirates. Arrius, who admires Ben-Hur’s courage and determination, offers to train him as a gladiator and charioteer. Ben-Hur declines the offer, claiming that God will aid him in his vengeance. When the Roman fleet encounters the Macedonians, Arrius orders all the rowers except Ben-Hur to be chained. Arrius’ galley is rammed and sunk, but Ben-Hur rescues him. Wrongly assuming defeat, Arrius attempts to atone by “falling on his sword,” but Ben-Hur stops him. After their rescue, Arrius is credited with the Roman fleet’s victory.

Arrius petitions Emperor Tiberius (George Relph) to free Ben-Hur, and adopts him as his son. Established again, Ben-Hur learns the Roman ways and becomes a champion charioteer. Returning to Judea, he meets Balthasar (Finlay Currie) and the Arab sheik Ilderim (Hugh Griffith). The sheik asks Ben-Hur to drive his quadriga in a spectacular race to be watched by the new Judean governor Pontius Pilate (Frank Thring), but Ben-Hur declines.

In Jerusalem, Ben-Hur learns that Esther’s arranged marriage didn’t occur and that she is still in love with him. He visits Messala and demands his mother and sister’s freedom, but the Romans discover that the women contracted leprosy in prison and expel them. They ask Esther not to tell Ben-Hur, and she obliges, telling him that they had died. As a result, Ben-Hur decides to seek vengeance on Massala by competing against him in the chariot race.

During the chariot race, Messala drives a chariot with blades; he attempts to destroy Ben-Hur’s chariot but destroys his own instead. Messala is fatally injured, while Ben-Hur wins the race. Before dying, Messala tells Ben-Hur that he can find his family “in the Valley of the Lepers.” Ben-Hur visits the leper colony, and observes from a distance his mother and sister.

Blaming the Romans for his family’s fate, Ben-Hur rejects his citizenship. Learning that Tirzah is dying, Ben-Hur and Esther take her and Miriam to see Jesus, but the trial of Jesus before Pontius Pilate has begun. Ben-Hur witnesses the crucifixion, while Miriam and Tirzah are miraculously healed during the rainstorm.

Credits:

Budget: $15 million

Running time: 212 Minutes

Oscar Nominations: 12

Picture, produced by Sam Zimbalist

Director: William Wyler

Screenplay (Adapted): Karl Tunberg

Actor: Charlton Heston

Supporting Actor: Hugh Griffith

Cinematography (color): Robert L. Surtees

Art Direction-Set Decoration (color: William A. Horning and Edward Carfagno; Hugh Hunt

Film Editing: Ralph E. Winters

Costume Design (color): Elizabeth Haffenden

Scoring (Dramatic or Comedy): Miklos Rozsa

Sound: Franklin F. Milton

Special Effects: A. Arnold Gillespie and Robert MacDonald, visual; Milo Lory, audible

Oscar Awards: 11

Picture

Director

Actor

Supporting Actor

Cinematography

Art Direction-Set Decoration

Film Editing

Costume Design

Scoring

Sound

Special Effects

Oscar Context

In 1959, “Ben-Hur” won over Preminger’s courtroom drama Anatomy of a Murder,” which lost in each of its 7 categories; the Holocaust drama, “The Diary of Anne Frank,” which received 7 nominations and won 3; Fred Zinnemann’s morality tale “The Nun’s Story,” which also lost in each of its 7 nominations, and the superb British drama “Room at the Top,” which won 2 out of its 6 nominations.

![]()