Past and present collide in complex and unexpected ways in Bad Education, Pedro Almodovar’s most personal film to date.

The new, dense film is more poignant than the more easily digested and enjoyable, All About My Mother and Talk to Her. In overall impact, and the significant place it occupies in his rich oeuvre, Bad Education is one of Almodovar’s strongest films.

Grade A: ***** out of *****

Commercially, Bad Education may not be as accessible and successful as the prize-winning films, Talk to Her or All About My Mother, but it’s a more ambitious and mature film, one that brings together strands of Almodovar’s gay films of the 1980s with those of his intimate relationship stories of the 1990s.

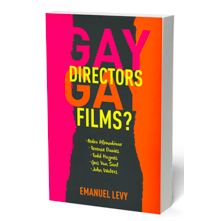

Almodovar is the subjet of my latest book:

Though drawing on personal experiences, Almodovar insists that Bad Education is not autobiographical. The origins of Bad Education go back to Almodovar’s Law of Desire. In that 1986 picture, the transsexual (played by Carmen Maura) goes into the church of the school where she had studied as a boy. Upon meeting a priest playing the organ in the choir, he asks for her identity, and she confesses to have been a pupil at the school and that he (the priest) was in love with her.

Almodovar says that he’s not interested in settling scores with priests who continue to bad-educated boys like him. In a press conference in Cannes, he disclosed: The church doesn’t interest me, not even as an adversary. If I needed to take revenge, I wouldn’t have waited forty years to do so. Indeed, while attacks of the corruption and hypocrisy of the Catholic Church are on the surface, that’s not what the movie is about.

Spanning 17 years, chronologically, the saga begins in 1964 and ends in 1980, with a crucial interval in 1977. Though a large part of the story is set in Madrid, the movie is not a reflection on the movida of the early 1980s. What interests Almodovar about that specific historic moment was the explosion of freedom, as opposed to the repression and obscurantism that prevailed in the 1960s, when he was growing up.

Though there’s some humor, Bad Education is neither a farce nor a comedy. It’s a quintessential film noir–as dark as they come–blending noir and crime elements with erotic melodrama, laced with personal memoirs and the director’s consistent exploration of obsession, death, and desire.

In previous films, Almodovar was inspired by and borrowed themes from Tennessee Williams and Joe L. Mankiewicz, and visual elements from Frank Tashlin and others. In his new movie, he sinks his teeth deep inside the noir territory. His brand of noir mixes excessive melodramas like Leave Her to Heaven, dark and incestuous family sagas like Mildred Pierce, obsessive romances like Laura, and the hard-boil literary tradition with its crime-thriller elements and criticism of society’s mores.

More specifically, Bad Education pays tribute to Billy Wilder’s Double Indemnity and Hitchcock’s Vertigo. Like those classics, Bad Education is about obsessive love, illicit affairs, double-dealing, and scandalous revelations. If the opening credits pay homage to Saul Bass, the loud and disquieting score by Alberto Iglesias score is in the spirit of Bernard Herrmann’s music for Hitchcock, specifically Psycho.

The first scene, set in 1980 Madrid, finds Enrique (Fele Martinez), a young gay director stuck with no idea or inspiration for his new feature. Out of the blue, he’s visited by Ignacio (Gael Garcia Bernal), a handsome man claiming to be his old classmate and first love. Ignacio, who now goes by the name of Angel and pursues an acting career, hands Enrique a story, The Visit, which is partly inspired by their childhood experiences, when they were abused by the school principal Father Manolo, and partly by Ignacio’s subsequent life as Zahara, a drug-addicted transvestite.

Bad Education might have been called Almodovar’s Secrets & Lies, though in a different way than Mike Leigh’s picture. Appearances are deceiving and, when it comes to identity, nothing is what it first seems to be. As soon as the viewers form an opinion of a character, Almodovar comes up with a challenging twist, such as the revelation that Ignacio has a “mysterious” brother.

The childhood episodes have a lyrical, dreamy quality about them, especially an idyllic scene out in the country, with the boys swimming and Ignacio singing, upon request, the Audrey Hepburn song, Moon River, from Breakfast at Tiffany’s. Father Manolo is genuinely in love with the young, angelic Ignacio, and his decision to separate him from Enrique is driven by obsessive jealousy.

Structurally, Bad Education has one of the most intricately woven plots I have seen in years. The movie is constructed as a labyrinth, with layers on top of layers, strands interfacing with other strands. Its masterful work in which symmetry works, often in reverse.

For example, the visitor who calls himself Mr. Berenguer and intrudes into Enrique’s set is recognized by him as Father Manolo, now dressed in civilian clothes and 17 years older than the last time they met, when Manolo expelled him from school. Now, it’s Enrique the director who expels Manolo-Berenguer from his office. However, when Manolo offers information about Ignacio’s death and Angel’s real identity, Enrique becomes intrigued, driven by the same suicidal curiosity that led him to work with Angel.

The metaphor of crocodiles, shown earlier in the film, finally comes full circle, making itself clear. While listening to Manolo’s story, Enrique begins to feel like the woman who threw herself into the pool of crocodiles–and hugged them while they ate her.

Almodovar borrows from noir the quintessential elements of deception, fatalism, double identity, crime, and desire. The novel aspect, though, is that in noir, the femme fatale is a woman, whereas in Bad Education it’s a man, or rather an enfant terrible (Bernal), a man who combines in his sultry and soulless bits of roles played by Barbara Stanwyck, Jane Greer, and Jean Simmons, to mention a few femme fatales. The scene in which Berenguer and Juan go to Valencia’s Museum of Giant Creatures, to plan a murder, pays tribute to the supermarket scene in Double Indemnity, in which Stanwyck (in blonde wig and dark glasses) and Fred MacMurray plan to murder her husband.

Almodovar is using the screen as a reflective mirror for both the protagonists and spectators. When Ignacio and Mr. Berenguer go to the movies after committing a murder, the theater they choose “happens” to be showing two French film noirs: Renoir’s The Human Beast, and Marcel Carne’s Therese Raquin. These movies involve similar situations to those of the men watching them. Leaving the theater, a devastated Berenguer complains, “It’s as if all the films were talking about us.” He’s not kidding, they do!

Fiction and reality continue to interface up to the end. When Berenguer visits Enrique’s set, he sees in front of the camera himself as Father Manolo–it’s a film about himself, written by one pupil (Ignacio) and directed by another (Enrique). Berenguer is thus contemplates his own past, as it’s narrated and deconstructed by his former pupils-victims.

The film’s density is reflected in its multiple layers, based on the duality, duplicity, and mirrors that inform and deform what the characters–and the viewers–see. There are no less than three layers. The first is the real story; the second is the story told by Ignacio in his short story (inspired by the real story); and the third is the story Enrique is adapting from the short story, which he visualizes as a film.

The double motif is expressed in the portrayal of desire. The passion that Father Manolo feels for the boy, and his abuse of power, turns him into an executioner. However, years later, when Manolo calls himself Berenguer and falls in love with Juan, he’s the one who becomes a victim. But the organizational principle of the text is that of the triad. Bad Education is a story of multiple trios. There’s the trio of the two pupils and the school principal, then there’s the trio of the two brothers and Mr. Berenguer, then there’s the trio of the director, actor, and Berneguer.

A triumph for Almodovar, and one of the year’s best pictures, Bad Education is a dark, personal meditation about the dual power of love to liberate and to enslave, to inspire and to destroy.