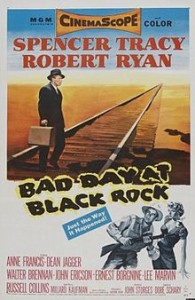

Bad Day at Black Rock, one of John Sturges’ best films, is a rare 1950s feature, one that dealt with bigotry and racism in general and discrimination against Japanese Americans in particular.

Grade: B+ (**** out of *****)

A self-conscious genre film, the tightly plotted and tautly directed Bad Day at Black Rock is a modernized traditional Western, aiming to confront social problems explicitly (racial prejudice) and implicitly (McCarthy witch- hunting and the Blacklist).

The film begins and ends at the railroad station, an abandoned structure in extreme state of dilapidation. Set in the prairie, with sand dunes rising and falling monotonously, the railroad tracks reach endlessly into the horizon.

The town of Black Rock is tiny, dismal, and forgotten, surrounding by land, which has the quality of immutability; nothing breathes or moves. It is in the middle of nowhere: 32 miles from Sand City, 156 from Phoenix, and 211 from Los Angeles. Isolated, there are no buses or other means of transportation. The whole town is centered on Main Street, a desolate, dirty and dusty strip.

The town of Black Rock is tiny, dismal, and forgotten, surrounding by land, which has the quality of immutability; nothing breathes or moves. It is in the middle of nowhere: 32 miles from Sand City, 156 from Phoenix, and 211 from Los Angeles. Isolated, there are no buses or other means of transportation. The whole town is centered on Main Street, a desolate, dirty and dusty strip.

Stylistically, the film begins with a series of long shots; the composition of each has the texture of American primitive painting, best exemplified in the work of Grant Wood. Filmed in CinemaScope, the sweeping vistas of the desert dwarf the town and its inhabitants into midget’s proportions.

One day, a robust, a one-armed stranger named John Macready (Spencer Tracy) descends from the train. Wherever Macreday turns for assistance, he is rebuffed and needled. Most of the actions take place at Sam’s (Walter Sande) Sanitary Bar and Grill. The elderly Doc Velie (Walter Brennan) functions in multiple roles: as notary public, mortician, and veterinarian. The townspeople speculate about the identity of the mysterious stranger who plans to stay “just about 24 hours.” “He’s no salesman,” says Velie, “that’s sure, unless he’s peddling dynamite.” “He can only mean trouble,” says Hector David (Lee Marvin), a vulgar lout. Indeed, Macready’s mission is to locate a Japanese farmer, whose son has died in action, to give him a posthumous war medal.

It’s a nasty town, tormented by hatred and guilt; Smith has infected the whole town with his “bad seed.” Smith explains that the residents are “a little suspicious of strangers,” a “hangover from the old days, the Old West.” “I thought the tradition of the Old West was hospitality,” says Macready. Smith resents the fact that people are always looking for “something in this part of the West.” “To the historian, it’s the ‘Old West.’ To the book writers, it’s the ‘Wild West.’ To the businessman, it’s the ‘Underdeveloped West.'” He admits they are “backward and poor, but this place is our West, and wishes “they’d leave us alone.” Indeed, Macready’s arrival in town changes everything: He is like “a fever, an infection that is spreading.”

It’s a nasty town, tormented by hatred and guilt; Smith has infected the whole town with his “bad seed.” Smith explains that the residents are “a little suspicious of strangers,” a “hangover from the old days, the Old West.” “I thought the tradition of the Old West was hospitality,” says Macready. Smith resents the fact that people are always looking for “something in this part of the West.” “To the historian, it’s the ‘Old West.’ To the book writers, it’s the ‘Wild West.’ To the businessman, it’s the ‘Underdeveloped West.'” He admits they are “backward and poor, but this place is our West, and wishes “they’d leave us alone.” Indeed, Macready’s arrival in town changes everything: He is like “a fever, an infection that is spreading.”

Smith’ reaction to being rejected is perverted, using it as an excuse for capturing the unexpectedly valuable land of a Japanese farmer. The Japanese farmer got there three months before Pearl Harbor, and made wonders with the sterile and barren land, but he was shipped to one of those relocation centers. The town is responsible for burning out his farm and killing him. Nobody even knew Komako had a son, Joe, let alone a war hero who saved Mercado’s life in Italy.

Macready knows “there’re not many places like this in America,” but as far as he is concerned “even one (town) is too many.” A man of action, he is determined to perform “one last duty” before he resigns from the “human race.” Doc thinks Macready would settle down in Los Angeles, “that hot bed of pomp and vanity.” But Macready says he stays on there, because “it’s a good jumping off place–to the Islands, for Mexico, Central America.”

Macready knows “there’re not many places like this in America,” but as far as he is concerned “even one (town) is too many.” A man of action, he is determined to perform “one last duty” before he resigns from the “human race.” Doc thinks Macready would settle down in Los Angeles, “that hot bed of pomp and vanity.” But Macready says he stays on there, because “it’s a good jumping off place–to the Islands, for Mexico, Central America.”

Gradually, Macready forces Doc and Liz to realize that concealing facts makes them a party to the crime, just as guilty as the committer of crime. Doc is the first to change his mind. “There comes a time, when a man’s just got to do something,” he tells the sheriff. “No man is useless, if he’s got a friend.” “There’s a difference between clinging to the earth and crawling on it,” says Doc.

In the film’s coda, the town regains its collective consciousness and respect, symbolized in Doc’s request for the war medal. “We need it. It’s something we can maybe build on.” The town is wrecked, just as bad as it was bombed out. Maybe it can come back.” “Some towns come back. Some don’t,” says Macready before leaving, “It depends on the people,” reaffirming populist ideology. In the film’s last shot, having intruded and redeemed Black Rock, the hero departs. Gathering speed, the train diminishes far into the horizon, and the mysterious stranger turns to his unknown future (a modern version of Shane’s hero).

In its sustained tension, Bad Day is a melodrama of retribution bearing resemblance to Zinnemann’s High Noon, though its suspense is tighter than in the l952 Western. As in High Noon, the town is guilt-ridden and literally paralyzed. The relationship between Kane (Gary Cooper) and Hadleville is similar to that between Macready and Black Rock. Like Kane, Macready is inner-directed, a man of conscience, an individual pitted against the masses.

In its sustained tension, Bad Day is a melodrama of retribution bearing resemblance to Zinnemann’s High Noon, though its suspense is tighter than in the l952 Western. As in High Noon, the town is guilt-ridden and literally paralyzed. The relationship between Kane (Gary Cooper) and Hadleville is similar to that between Macready and Black Rock. Like Kane, Macready is inner-directed, a man of conscience, an individual pitted against the masses.

Both Kane and Macready play on the collective guilt of the town, though the former fails. In both, the hero is isolated–visually both are seen walking in empty streets. Both risk their lives for the cause. But Macready is a more complex character, full of contradictions. And unlike Will Kane, he is not an official representative of the law. A private citizen, his danger is all the more significant. In terms of messages, both support individualism, the role of charismatic leader Still, in High the whole town is condemned; Kane has to fight alone.

In the film, the guilt of the residents increasingly torments them and slowly they begin to change in the right direction. As a result, Bad Day ay Black Rock ultimately reaffirmed the power of reason and democracy.

My Oscar Book

Oscar Context

Oscar Nominations: 3

Director: John Sturges

Actor: Spencer Tracy

Screenplay: Millard Kaufman

Oscar Awards: None

This is the only Best Director nomination of John Sturges, who lost the award that year to Delbert Mann for Marty.

Credits:

Directed by John Sturges

Screenplay by Don McGuire, Millard Kaufman, based on “Bad Time at Honda” (1947 short story in The American Magazine) by Howard Breslin

Produced by Dore Schary

Cinematography William C. Mellor

Edited by Newell P. Kimlin

Music by André Previn

Distributed by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer

Release date: January 7, 1955

Running time 81 minutes

Budget $1,288 ,000

Box office $3,788,000

Cast

Spencer Tracy as John J. Macreedy

Robert Ryan as Reno Smith

Anne Francis as Liz Wirth

Dean Jagger as Sheriff Tim Horn

Walter Brennan as Doc Velie

John Ericson as Pete Wirth

Ernest Borgnine as Coley Trimble

Lee Marvin as Hector David

Russell Collins as Mr Hastings

Walter Sande as Sam, the diner owner