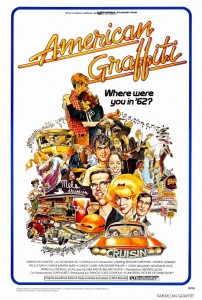

George Lucas’s nostalgic view of youth, American Graffiti, set in California in 1962, was meant to be a metaphor of “what we once had and lost.”

George Lucas’s nostalgic view of youth, American Graffiti, set in California in 1962, was meant to be a metaphor of “what we once had and lost.”If Bogdanovich’s The Last Picture Show presents a gloomy portrait of small-town life just prior to the advent of television, American Graffiti moves the setting forward by a decade, to 1962, when television had already established itself as the mainstay of American pop culture. However, as far as youths were concerned the relevant medium is radio and the music is rock; radio is shown to be their whole lifetime. American Graffiti is only nominally set in 1962, for the icons and symbols in the story really belong to the late 1950s.

Take, for example, the cars. Some girls cruise in a Studebaker; Steve drives a white 58 Chevy; and Laurie in a ’58 Edsel.

The songs are also of the late 1950s: in the opening scene, at Mel’s Drive In, we hear “Rock Round the Clock,” then Dale Shannon’s “The Little Runaway.” There is also music by the Platters, the Beach Boys, Flash Cadillac, and the Continental Kids. The movie stars that are emulated by the youths are Connie Stevens and Sandra Dee for the girls, and (the myth of) James Dean and Elvis Presley for the boys.

There is saturation of mass media, and their influence is pervasive; the kids’ dialogue makes many references to pop culture. Debbie tells one boy he is like the Lone Ranger, and Curt falls in love with a girl from Citizen Kane. The recurrent audio-visual motif is a blast of rock music, coming from an endless stream of cars cruising around the block in Modesto, a small town in Northern California. The car cruising takes the form of a modern dance piece, in which the relations among dancers (cars in the film) form, shift, separate, and reform–either by logic or by chance.

There is saturation of mass media, and their influence is pervasive; the kids’ dialogue makes many references to pop culture. Debbie tells one boy he is like the Lone Ranger, and Curt falls in love with a girl from Citizen Kane. The recurrent audio-visual motif is a blast of rock music, coming from an endless stream of cars cruising around the block in Modesto, a small town in Northern California. The car cruising takes the form of a modern dance piece, in which the relations among dancers (cars in the film) form, shift, separate, and reform–either by logic or by chance.

Modesto’s moral center is not a type like Sam the Lion, an old-time moralist, but Wolfman Jack, the disk jockey, whose show unifies the town’s kids. Indeed, the disk jockey, as a profession and the town’s moral focus, provides a new cultural symbol in youth films. Wolfman interacts with each member separately, and each youngster perceives him in different way. He serves as a secret friend to each one of them. Wolfman is not seen much, but his presence his felt through the music he chooses for them to listen. “The Wolfman been everywhere and he seen everything,” people say in admiration, “he got so many stories, so many memories.” As the community’s expressive leader, Wolfman later arranges for a (telephone) interview between Curt and the unknown blonde he falls in love with, thus helping fulfill latent dreams.

Modesto’s moral center is not a type like Sam the Lion, an old-time moralist, but Wolfman Jack, the disk jockey, whose show unifies the town’s kids. Indeed, the disk jockey, as a profession and the town’s moral focus, provides a new cultural symbol in youth films. Wolfman interacts with each member separately, and each youngster perceives him in different way. He serves as a secret friend to each one of them. Wolfman is not seen much, but his presence his felt through the music he chooses for them to listen. “The Wolfman been everywhere and he seen everything,” people say in admiration, “he got so many stories, so many memories.” As the community’s expressive leader, Wolfman later arranges for a (telephone) interview between Curt and the unknown blonde he falls in love with, thus helping fulfill latent dreams.

The nondiegetic music in American Graffiti suggests that all the kids, no matter where they are, are listening to the same radio program. The off screen music performs narrative and ideological functions, cementing the otherwise narrative’s episodic structure and interweaving the adolescents’ crisscrossing paths.

The nondiegetic music in American Graffiti suggests that all the kids, no matter where they are, are listening to the same radio program. The off screen music performs narrative and ideological functions, cementing the otherwise narrative’s episodic structure and interweaving the adolescents’ crisscrossing paths.

Modesto is a self-contained entity; there are no excursions out of town. The action itself is confined to one long hot summer night, from sunset to sunrise, during which the adolescence of four male youngsters comes to a dramatic end. Modesto is the kind of town that changes image and personality; the alternation of day and night sequences captures this variable quality. During the day, one sees on Main Street a line of used car-lots, small shops, department stores, and greasy spoons. At night, one sees the flashing, neon-lighted signs, and an endless parade of cars, some customed, others lowered. The town looks much more “glamorous” at night; Haskell Wexler’s excellent cinematography emphasizes the town’s dazzling kaleidoscopic feature at night.

The narrative’s real star is not human, but an object–the car– and the lifestyle it embodies. These adolescents don’t seek Nature to regain their emotional balance, solve their identity crises, or make love. The car is a symbolic substitute for Nature, providing emotional security, physical protection, and comfortable environment. It serves as a metaphor to America’s innocence and naivet in the early 1960s, when isolationism in foreign politics was still strong. Significantly, most of the interaction in American Graffiti takes place through the cars’ windows, but it is a rich communication, exchange of provocations, flirtatious remarks, and insults. A convenient shield, the car’s window if the only window to the real, outside world. George Lucas described his film as “a metaphor of what we once had and lost.”

The narrative’s real star is not human, but an object–the car– and the lifestyle it embodies. These adolescents don’t seek Nature to regain their emotional balance, solve their identity crises, or make love. The car is a symbolic substitute for Nature, providing emotional security, physical protection, and comfortable environment. It serves as a metaphor to America’s innocence and naivet in the early 1960s, when isolationism in foreign politics was still strong. Significantly, most of the interaction in American Graffiti takes place through the cars’ windows, but it is a rich communication, exchange of provocations, flirtatious remarks, and insults. A convenient shield, the car’s window if the only window to the real, outside world. George Lucas described his film as “a metaphor of what we once had and lost.”

The movie presents that era’s complacency and apathy, along with its political naivet and insularity. Instead of making explicit statements about the past’s superiority to the present, the nostalgia is put in historical perspective, allowing viewers to decide for themselves what their attitude are toward those years. This is one portrait of America’s past, American Graffiti seems to say, and it’s up to the viewers to determine how this particular past has shaped–or led to–the present.

The four protagonists are high school graduates at a turning point. Their crucial dilemma is staying in town or going to college. Curt (Richard Dreyfuss) and Steve (Ron Howard) are about to go to college, but Curt is hesitant about it. “I was thinking I might wait a year,” he tells Steve, “go to city.” As in other movies, the kids are aware of the town’s possibilities and limitations. “You can’t back out now!” says Steve, “We are finally getting out of this turkey town, and now you want to crawl back into your cell.” The radio station’s manager concurs with Steve: “No offense to your home town here, but this place ain’t exactly the hub of the universe.” The manager’s frustration derives from his realization that “there’s a whole big beautiful world out there…and here I sit sucking Popsicles.”

The four youngsters represent different types. Attractive and pleasant, Steve serves as his class’s president. Curt is the bright, inquisitive intellectual; winning a prestigious fellowship assures him that he would go to college. Less handsome, Terry the Toad (Charlie Martin Smith) is the type who follows: Worshipping Steve, he gets to use his grand impala. John Milner (Paul LeMatt) is a negative reference figure: at 22, he is still immature, emulating James Dean. He drives a yellow ’32 Ford deuce coupe, puffing on a Camel, with his butch haircut molded on the sides into a docktail. John is the simpleton, anti-intellectual type, unimpressed with college. “You probably think you’re a big shot,” he tells Steve, “but you’re still a punk.” The champion of drag-racing, John considers himself a ladies’ gentleman.

The conversations carried by the youngsters may sound trivial–to adult viewers–but are important to them. At the girls’ lavatory, Laurie (Cindy Williams) is worried because Steve is going away. Her friend Peg Fuller is sure she’ll forget him in a week; if she’s elected senior queen, she’ll have many admirers. “Remember what happened to Evelyn Chelnick when Mike went into the Marines” says Peg, trying to cheer Laurie up, “She had a nervous breakdown and was acting so wacky she got run over by a bus!” At the same time, at the boys’ lavatory, the guys work as intensely on their coiffures as the girls do, smoothing their ducktails, primping their glossy waterfalls, and waxing their crew cuts to stand stiff. After teasing Eddie for using a pimple cream, Steve applies it on his neck. Eddie is surprised to hear about Steve and Laurie’s “arrangement.” “We’re still going together,” says Steve, “but we can date other people;” it is clear, however, this was his idea. To make him jealous, Laurie goes with a hot-rodder, but at the end they are reunited after an accident. The drag race in American Graffiti lacks the consequential effects of a similar race in Rebel without a Cause, though the Modesto youngsters have probably learned about such races from the James Dean movie.

Focusing on four boys, American Graffiti takes an exclusively male point of view. If the movie were made a few years later, it would have had to include stronger female parts. The girls in the film exist as romantic interests for the boys, lacking personality of their own. Still the movie shows different types of girls: Laurie is compared with Debbie in the way they relate to love and sex. Laurie’s ideal is to have a monogamous relationship, whereas Debbie is more pragmatic.

The narrative ends with Curt’s departure to college out East. His plane takes off while the soundtrack plays “Goodnight Sweetheart.” What were the options of small-town kids at the time: go to college, run away to the Big City, or stay in town and live a complacent and stifling life. However, with all his ambition to pursue his studies, Curt’s departure from town conveys the price, the loss of intimate friendships he will never experience again. (In Stand By Me, in 1986, Richard Dreyfuss played another writer who, looking back on his life, realize he never had the same intimate friendships he had as a teenager).

But Curt also knows that if he stayed in town, his life could have turned worst. The fate of the four friends is printed on screen, and it is shocking because it violates the former nostalgic and pleasant mood. The viewers are suddenly thrown off balance, from a fantasy-dream to a newsreel. The cards tell that John Milner was killed by a drunk driver, in 1964. Terry Fields was reported missing in action in Vietnam, in 1965. Steve Bolander is an insurance agent in Modesto. And Curt Henderson is a successful writer who went to Canada (because of the draft).

Feminist critics pointed out correctly that the narrative suffers from a sexist bias, charging that the filmmakers obviously did not find it necessary to report what has happened to its female characters.