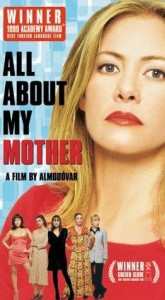

Announcing his newly-gained maturity while still reflecting boundless creativity, All About My Mother(“Todo sobre mi madre”) is the first in a series of four great films made between 1999 and 2006, representing the best phase of Almodovar’s career.

All About My Mother, my personal favorite of Almodovar’s films, is one of his universally acknowledged masterpieces, and also one of his most commercially profitable films.

A summation work, “All About My Mother” (“Todo sobre mi madre”) is a fiercely emotional yet unsentimental movie representing thematic, visual, and tonal synthesis of his entire work. It is the first Almodovar film to be shown at the prestigious Cannes Film Festival, where most of his works would premiere in the future. For this accomplished film, he won the Cannes Best Director Award, though many critics thought he should have won the Palme d’Ór. “All About My Mother” was the second Almodovar picture to be nominated for the Best Foreign Language Film Oscar, and his first to win.

My book about Almodovar:

Arguably his warmest film, “All About My Mother” represents a loving tribute to women in their various shapes, ages, classes, and professions. On the surface a woman’s melodrama, the movie covers the entire range of emotions: loss, grief, reconciliation, camaraderie, and redemption. It depicts a circle of women who confront with forceful courage all kinds of ills: terminal disease (AIDS), abandonment by husbands and lovers, old age and dementia, unplanned pregnancy, and death. Well-balanced, the film mixes elements of comedy and drama, sentiment and humanity in equal measure, all contained in a multi-layered narrative of extraordinary cohesiveness and emotional power. If the plot is too melodramatic and the setting too theatrical, the characters and performances are decidedly not—they are grounded in realistic contexts. Moreover, there is no surface glamour, despite the theatricality. The close-ups of the characters—the mother-nurse Manuela, the aging diva Huma, the terminally-ill nun Rosa, the dying transsexual Lola, the drug-addict lesbian Nina–reveal ravaged and wrinkled faces of women who have gone through life’s painful experiences.

Arguably his warmest film, “All About My Mother” represents a loving tribute to women in their various shapes, ages, classes, and professions. On the surface a woman’s melodrama, the movie covers the entire range of emotions: loss, grief, reconciliation, camaraderie, and redemption. It depicts a circle of women who confront with forceful courage all kinds of ills: terminal disease (AIDS), abandonment by husbands and lovers, old age and dementia, unplanned pregnancy, and death. Well-balanced, the film mixes elements of comedy and drama, sentiment and humanity in equal measure, all contained in a multi-layered narrative of extraordinary cohesiveness and emotional power. If the plot is too melodramatic and the setting too theatrical, the characters and performances are decidedly not—they are grounded in realistic contexts. Moreover, there is no surface glamour, despite the theatricality. The close-ups of the characters—the mother-nurse Manuela, the aging diva Huma, the terminally-ill nun Rosa, the dying transsexual Lola, the drug-addict lesbian Nina–reveal ravaged and wrinkled faces of women who have gone through life’s painful experiences.

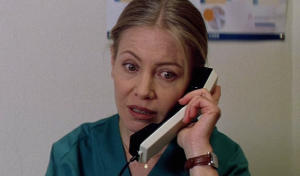

The opening credits appear and dissolve as the camera pans over medical objects, drips and dials in the primary colors of blue, red, and yellow, colors that will serve as the film’s visual codes, again signaling issues of life and death, birth and demise. The tale is dominated by women—many women. The heroine, Manuela (Cecilia Roth, the Argentinean actress who had starred in “Labyrinth of Passion”), is a single mom living in Madrid with her only son, Esteban (Eloy Azorin). On his seventeenth birthday, Manuela takes Esteban to see a production of Tennessee Williams’ “A Streetcar Named Desire,” starring the famous star, Huma Rojo (Marisa Paredes). Manuela confesses to Esteban that she had once played Stella to his father’s Stanley Kowalski in Williams’ play, and so we anticipate this information to come back later in the plot, as it does. The play’s legendary last scene, when Blanche is taken away after descent into madness, is repeated several times, though each time a different actress is playing Stella.

The opening credits appear and dissolve as the camera pans over medical objects, drips and dials in the primary colors of blue, red, and yellow, colors that will serve as the film’s visual codes, again signaling issues of life and death, birth and demise. The tale is dominated by women—many women. The heroine, Manuela (Cecilia Roth, the Argentinean actress who had starred in “Labyrinth of Passion”), is a single mom living in Madrid with her only son, Esteban (Eloy Azorin). On his seventeenth birthday, Manuela takes Esteban to see a production of Tennessee Williams’ “A Streetcar Named Desire,” starring the famous star, Huma Rojo (Marisa Paredes). Manuela confesses to Esteban that she had once played Stella to his father’s Stanley Kowalski in Williams’ play, and so we anticipate this information to come back later in the plot, as it does. The play’s legendary last scene, when Blanche is taken away after descent into madness, is repeated several times, though each time a different actress is playing Stella.

For most of her adulthood, Manuela has lived a life of quiet desperation, replete of lies–small and big lies–to herself and to others. Manuela, who has told Esteban that his father had died before he was born, promises to tell him more about his lineage after the show. Sadly, this never happens due to a fatal car accident. On a fateful rainy night, Huma and her co-star and lover Nina (Candela Pena) board a taxi after the show. Running after them for an autograph, Esteban is hit by the taxi. The devastated Manuela, who witnesses the accident, is a nurse who organizes seminars to counsel relatives of prospective organ donors. Having decided to donate Esteban’s body, she violates the rules and takes a trip to meet (incognito) the recipient of her son’s organs. Almodovar inserts a close-up of the chest of the middle-aged recipient, when he gets out of the hospital blessed with Esteban’s young heart.

After the tragedy, Manuela tries to bring together the disparate and unfinished elements of her life. Honoring Esteban’s last wish to find his father, who’s also named Esteban, she returns to her hometown Barcelona to seek him out. The boy’s father is a transsexual, Lola the Pioneer (Toni Canto), who doesn’t know he has a child because Manuela never told him. Manuela later relates how Esteban became Lola in Paris, when he got “a pair of breasts much bigger than mine.”

After the tragedy, Manuela tries to bring together the disparate and unfinished elements of her life. Honoring Esteban’s last wish to find his father, who’s also named Esteban, she returns to her hometown Barcelona to seek him out. The boy’s father is a transsexual, Lola the Pioneer (Toni Canto), who doesn’t know he has a child because Manuela never told him. Manuela later relates how Esteban became Lola in Paris, when he got “a pair of breasts much bigger than mine.”

Having left Barcelona eighteen years earlier, Manuela is now looking for Esteban-Lola at a sleazy pick-up site. In this marginal milieu, dirty older men cruise hustlers and prostitutes, both male and female. Upon arrival (by taxi, Almodovar’s favorite mode of transport), Manuela encounters La Agrado (Antonia San Juan), a battered transsexual beaten up in the open fields by a frustrated customer. La Agrado has big fake breasts and a huge real cock (More about it later). She turns out to be Manuela’s old friend from their Barcelona days. She is named La Agrado, because, as she explains, “I always agree.”

Two decades ago, La Agrado lived with Manuela and Esteban’s father, before the latter had sex-change operation. La Agrado complains to Manuela that she had taken in the sickly HIV-positive Lola, but the ungrateful Lola ran off with her money and possessions. Through Agrado, Manuela meets Sister Rosa (Penelope Cruz), a nun bound for missionary service in El Salvador. Manuela then becomes personal assistant to Huma, the stage actress whom her son had admired. She helps Huma manage her life, which includes controlling Nina, her tempestuous, drug-addicted younger lover, who periodically abandons her. Deciding to change her life, La Agrado goes to see Sister Rosa for counseling. She learns, however, that it’s Sister Rosa who needs help–Rosa now carries the HIV virus after sleeping with Lola. Though initially resistant, Manuela nurses Sister Rosa through her pregnancy, the birth of her child, and eventually her death (at childbirth). In the climax, Manuela confronts Lola, the dying transsexual and her son’s father. Manuela bring ups the baby-boy, also named Esteban, and all ends well when the third Esteban defeats the lethal HIV virus.

Like other features, this film deals with the binary oppositions of procreation and death, creativity and stagnation, individual and community, self-sacrifice and social redemption, love and loneliness. As in most Almodovar’s films, for every death, there’s new life. Esteban’s heart beats within another man. Lola transmits the virus to Rosa but her baby miraculously recovers. Esteban never sees the photo of his father, but his father (Lola) sees the photos of his dead son (by Manuela) and learns of the existence of his other son (by Rosa).

Like other features, this film deals with the binary oppositions of procreation and death, creativity and stagnation, individual and community, self-sacrifice and social redemption, love and loneliness. As in most Almodovar’s films, for every death, there’s new life. Esteban’s heart beats within another man. Lola transmits the virus to Rosa but her baby miraculously recovers. Esteban never sees the photo of his father, but his father (Lola) sees the photos of his dead son (by Manuela) and learns of the existence of his other son (by Rosa).

Structurally, unlike “Live Flesh,” which was circular, the story unfolds in linear mode, using only a few flashbacks. In the first, Manuela recalls the performance of “A Streetcar Named Desire,” which she had seen with her son on the night he was killed. The second and third flashbacks are inserted when Manuela tells Huma about her son, and Huma recalls vividly that rainy night, when she got a glimpse of the boy through the taxi’s window.

Consistent with Almodovar’s worldview, in the end, the show, just like life itself, must go on. La Agrado, the “chick with dick,” takes on the stage after a performance is cancelled–Huma and Nina are both hospitalized after a fight. Proving that any woman has some acting skills, the likable La Agrado gives the audience a choice to leave or to stay, and several leave. Performing his/her own life story as a transsexual endowed with both male and female parts, La Agrado takes equal pride in her natural big penis and her big fake breasts. “A woman is authentic only in so far as she resembles her dream of herself,” La Agrado proudly exclaims. Each of his/her body parts has a price in the market place, except for her penis, which is a vital part for procreation as well as object of pleasure.

Despite the occurrence of tragic events, humor prevails in the most devastating situations, as when Sister Rosa suddenly proclaims, “Prada is perfect for nuns,” or when Huma discloses, Ï have not had one of those (penises) in a long time,” or when La Agrado performs on stage, describing each of her organs. Unity is brought to the narrative by a single character, the dying Lola who has affected and infected all of the women, albeit in different ways. There is a price to be paid, however, and before dying, Lola sums up her life in one sentence: “I was always excessive, and now I am very tired.”

Almodovar brings together the diverse characters in masterful two-shots. In the first act, mother and son are in the same frame, whether watching Bette Davis on TV, or watching Huma performing on stage. Making a special dinner for her son on the night before his birthday, Manuela is in the kitchen, rushed by Esteban to the living room as “All About Eve” is about to begin playing on TV. They always change titles, Esteban complains. In Spanish, the movie is retitled “Eve Unveiled” (“Eve Desnuda,” which literally translates into Naked Eve, a la Goya’s painting, “Maya Desnuda”). Eagerly waiting for midnight, Manuela enters into his room with her personal birthday gift, Truman Capote’s book. Reduced to childhood, when she used to tuck him in bed, Esteban asks his mom to read aloud. Densely self-referential, “All About My Mother” is allusive to works by other directors and playwrights. Manuela is reading loud to her son from Capote’s book, “When God hands you gift, he also hands you a whip, and the whip is intended solely for self-flagellation.” Capote’s often-quoted line becomes a running motif of Almodovar’s text.

Manuela shares the screen with each of the characters, Huma, Rosa, La Agrado, even the initially antagonistic Rosa’s mother. But significantly, Manuela doesn’t share the same space in the crucial reunion with her ex-husband. Almodovar cuts sharply between the two, who lost touch decades ago and can never occupy the same frame and universe again. With Esteban’s imminent death, Manuela is spared of taking care of yet another individual, but if needed to, she would have.

On the one hand, “All About My Mother” is a glossy melodrama, modeled partly on Douglas Sirk’s visual splendor, epitomized in “All That Heaven Allows,” ”Written on the Wind,” and “Imitation of Life,” all 1950s Hollywood films for which Almodovar has admiration. However, unlike the detached and ironic tone of Sirk’s works, the tone of Almodovar’s film is lyrical, warm, meditative, and decidedly non-ironic and non-cynical. And while Almodovar celebrates the work of American writers and directors (Capote, Williams, Mankiewicz), he never lets the viewers forget that he is still a Spanish director. “All About My Mother” concludes with a specific reference to Spain’s indigenous culture, showing Huma resuming her real calling, the theater. She is now rehearsing the part of the rigid matriarch in Garcia Lorca’s best-known play, “Blood Wedding.”

Several scenes are set in the theater, a common domain of melodrama as a distinct genre, and Almodovar’s use of this particular milieu is strategic. The most crucial scenes take place backstage, in the dressing rooms, and they are played for earnest rather than for satirical points, as is the case of the actress (Lora) Lana Turner plays in Sirk’s “Imitation of Life,” a title that Almodovar would never use, because for him, there’s no such thing. Almodovar also cites his own pictures. Like “The Flower of My Secret,” this movie centers on one woman’s grief, Manuela’s loss of her only son whom she had raised alone. The movie’s theater scenes of “A Streetcar Named Desire,” include the one in which Blanche DuBois is carried out of Kowalski’s house after recycling the legendary line, “I’ve always depended on the kindness of strangers.” These allusions to life, onstage and off, recall those of Cocteau’s monologue, “The Human Voice,” which Roberto Rossellini had made with Anna Magnani, in Almodovar’s film, “Law of Desire.”

At one point or another, each of the female protagonists is dependent on the kindness of a female stranger, to borrow from Williams’ play. This is manifest in the random encounters, accidental meetings, spontaneous friendships, and unexpected needs that are ultimately met by and through female camaraderie. The dubbed inserts of Bette Davis-Celeste Holme sequence from the 1950 Oscar-winning “All About Eve” parallel the Joan Crawford-Sterling Hayden clips from “Johnny Guitar” in Almodovar’s “Women on the Verge of Nervous Breakdown.” However, unlike the treacherous and greedy Eve Harrington in “All About Eve,” Manuela is good-hearted and generous to a fault femme who would never betray or deny the needs of other women. Unlike Blanche DuBois in “A Streetcar Named Desire,” Almodovar’s heroines may slip and “lose it” for a while, but they never really descend into madness (or commit suicide), holding onto their sanity to the bitter end with stoicism and humor.

Stylistically, too, there are references to and parallels between “All About My Mother” and other Almodovar pictures. La Agrado’s Channel suit matches Victoria Abril’s in “High Heels,” and her defiant claim, “I am authentic” recalls the claim made by Rossy de Palma’s maid in “Kika.” Showing remarkable facility in constructing seamlessly cohesive narratives, Almodovar is equally at ease with Prada and Truman Capote, Tennessee Williams and Lorca. He fuses pop culture and high culture, stylized aesthetics and genuine feeling, fake silicone breasts and real penises, performance on stage and necessary acting off stage.

This film celebrates women qua women, viewing them all as performers. “All About My Mother” is dedicated to Almodovar’s mother, who passed away shortly after the shoot was over, and to all the actresses who have played actresses on stage or in film, including Bette Davis, Gena Rowlands, and Romy Schneider. Manuela, who had once performed in “A Streetcar Named Desire” opposite her then husband, becomes an understudy–by necessity, not by calculated design. She represents the actress in all women, including the women in the director’s personal life. Almodovar said in an interview: “My initial idea was to make a film about the acting abilities of certain people who aren’t actors. As a child, I remember seeing this quality among the women in my family. They pretended much better than the men. Through their lies, they were able to avoid more than one tragedy.”

Addressing the charge of many critics that his cinema is essentially female-driven, Almodovar decided to focus his next feature on men—two in fact, and straight. “Talk to Her” (“Hable con ella”), made in 2002, is considered by many critics (not by me), to be Almodovar’s most serious and emotional work, a dramatic feature that’s extremely risky due to its subject matter and narrative form and style. The film’s critical status was reflected by its nominations for the Best Director and the Best Original Screenplay Oscars, winning in the latter category. Showing Almodovar’s humanism at its fullest, this fourteenth feature is an intimate exploration of friendship between two heterosexual men brought together under unusual but strangely similar circumstances.

Cast

Manuela (Cecilia Roth)

Huma Rojo (Marisa Paredes)

Nina (Candela Pena)

La Agrado (Antonia San Juan)

Sister Rosa (Penelope Cruz)

Rosa’s Mother (Rosa Maria Sarda)

Rosa’s Father (Fernando Fernan Gomez)

Lola (Toni Canto)

Esteban (Eloy Azorin)