On the 125th anniversary of the birth of two-time Oscar winner Fredric March, there are controversies and misconceptions that the long-time civil rights championhad once supported the Ku Klux Klan.

March is one of Classic Hollywood’s most accomplished actors, having been nominated for multiple Oscars, and winning two.

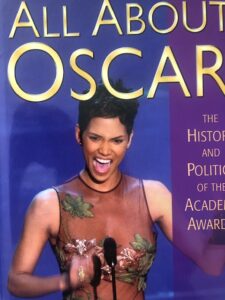

My Oscar Book:

Dual decisions in recent years to remove March’s name from a pair of performing-arts venues at two campuses of the University of Wisconsin — March’s alma mater — have drawn confusion, frustration and anger from film fans, the Hollywood community and activists alike.

The facts?

In 1919, March, then senior at the University of Wisconsin’s Madison campus, accepted invitation to join interfraternity honor society that shared a name with the Ku Klux Klan, though the group inviting March had nothing to do with the KKK.

It’s unclear why the honor society chose that particular name, but research did not reveal any connections between that group and the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan, the organization responsible for lynchings in the South.

When that group arrived on campus in 1922 with the intent of recruiting members, the UW-Madison honor society changed its name to avoid any association. George Gonis, a Milwaukee-based journalist, unearthed research from the then-president of the honor society, who noted that “many people confused it with the name of the non-collegiate secret organization of the same name.”

By early 1923, the honor society changed its name to Tumas, which can be derived from multiple meanings, including the name Thomas and, simply, “truth.” ‘

March had graduated in June 1920, and after stint in banking, headed to Broadway to forge his acting career. Few records exist of him taking part in any of the on-campus honor society’s activities—other than yearbook photo that gained attention in 2017.

One of March’s grandsons said that the actor’s surviving family had planned to donate his two best actor Oscar statuettes, won for 1931’s Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde and 1946’s The Best Years of Our Lives, to the university, but no longer plan to do so. “They certainly showed us that they don’t deserve them,” wrote Michael March Fantacci in email to Gonis. Added Fantacci, “It would have been more educational … to research my grandfather’s life than to cast wholesale judgment based on limited affiliation. When individuals fall into this trap, it can be understood. When educational institution does it, it’s more difficult to condone.”

Gonis is chief among the actor’s fans working to convince the university to reverse its decisions. “March and I share the same alma mater, plus my parents were huge movie buffs who were also active in the civil rights movement, so I grew up not only knowing who March was, but also knowing he really was one of the good guys in Hollywood,” Gonis says. “But every media report continued to quote people who hadn’t done any research. Meanwhile, within 5 to 10 minutes at the library, I was able to source all this material about his civil rights history.”

Born on August 31, 1897, March was passionate about social activism.

The actor died on April 14, 1975, at the age of 77.

March took part in NAACP activities for three decades, delivering keynote address at that organization’s 10th anniversary celebration of Brown v. Board of Education in 1964, while as teenager, he gave speeches condemning white supremacy. “Historians have identified speeches that we know March selected and delivered as a youth, all three devoted to human freedom and liberty,” Gonis explains. “Two of the speeches, ‘Invective Against Corry’ and ‘Spartacus to the Gladiators,’ are confirmed by eyewitnesses, newspaper accounts, March himself and Wisconsin-state entry papers for the state-run annual high school oratory competitions.”

During his Hollywood career, March was front and center when members of the film industry protested the House Un-American Activities Committee, which targeted actors like him, Bogart and Katharine Hepburn.

Karen Kramer, the wife of the director Stanley Kramer (who produced So Ends the Night and directed Inherit the Wind), notes: “In our industry, it’s extremely well known that March was fierce fighter for civil rights. My concern was whether the parties who accused him had done all their due diligence; had they looked at all the facts? You are entitled to your opinion, but you are not entitled to ignore the facts.”

Gonis and Kramer banded together to ask influential members of Hollywood to sign a letter advocating for the decision to be reversed. That letter, sent September 2021, included 30 signatures from Louis Gossett, Jr., Reggie Jackson, the late Ed Asner, Turman and others. “Rush to judgment is never the right way to go, especially if someone is not around to defend themselves,” Turman says. “We’re doing a lot of this cancel culture lately, and it’s a slippery slope that has to be navigated carefully. I’m in favor of using good judgment and some sort of vision to give you clarity and help you know where you stand.”

Turman’s next role is in Rustin, about gay civil rights leader Bayard Rustin, who organized the 1963 March on Washington. The film, from Higher Ground Productions, founded by Barack and Michelle Obama, premiered on Netflix in 2023 and co-stars Turman as Asa Philip Randolph, labor unionist and civil rights activist.

Recent editorials, including the N.Y. Times, also support renewed conversation about the decision. But for now, March’s name will not be restored to UW’s theaters. “There are no plans for the institution to revisit the issue,”

John Lucas, a university spokesperson, said in August 22 email. “In lieu of the theater naming, March is now included in a historic storytelling display on the same floor as the Play Circle as recognition of his role in our university’s history.”