Hawke: Waiting 12 Years to Make Linklater’s ‘Blue Moon’

At 54, Ethan Hawke is at the peak of his career. He has earned four Oscar nominations but no wins, and he’s perfectly fine keeping it that way.

Denzel Washington said it to me when I lost for Training Day: “Don’t worry. You don’t want to win it yet. It’ll mean so much more.’ He was like, ‘You’ve got a lot of good work to do.’”

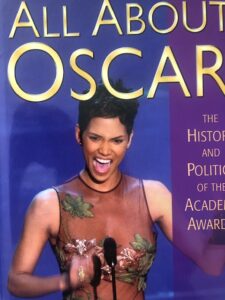

My Oscar Book:

For Hart, who with Rodgers had been “basically the Lennon and McCartney of their generation,” the evening represented both celebration and obsolescence. “Larry Hart, my character, would be dead within a few months of that party,” Hawke says. “And what would that have been like for him?

Hawke’s approach to his career — bouncing between indies and blockbusters, writing novels, and directing documentaries — stems partly from witnessing his friends struggle with early acclaim.

Hawke shares the screen with Andrew Scott, who plays Rodgers. Hawke had seen Scott perform “Hamlet” 15 years earlier and immediately recognized his talent.

One particularly grueling day, Hawke and Scott worked through a seven-page scene that required them to condense 25 years of friendship into a single argument. When Hawke checked his phone after wrapping, he discovered his wife had texted him to congratulate Scott on receiving 19 Emmy nominations that morning.

“Blue Moon” arrives via Sony Pictures Classics, one of few distributors still championing mid-budget adult dramas in an algorithm-driven landscape.

“Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead,” Lumet’s last film

I feel so lucky that it was Sidney Lumet’s last film. He was 83 years old, and I’ve always thought that if that exact same film had been made by a 27-year-old, everyone would have talked about it. Critics would have said, “Who is this new voice?” because it’s blistering, tough, and unsentimental. It’s like a Greek opera — two brothers who kill their mother. It’s so hardcore.

“Blue Moon”?

Linklater was the main reason for doing it. But also, I don’t think any other director would have thought of me for that part. It says a lot about our friendship that he knew this character was in me, he curated that performance.

I think he was waiting for me to get older. Most directors won’t wait for an actor for two weeks — they’ll just find someone else. But Rick waited over a decade. That says everything about who he is.

Reflecting on your own legacy?

I think it’s a dangerous way to think. I’m reaching an age where people make me think about it — like when you go to Telluride Film Festival and they show a clip reel of your life’s work. It’s a strange feeling. I’ve felt like a cat my whole life — just getting dropped off buildings, trying to land on my feet, trying to stay alive and keep a career. I feel so grateful to still be doing it — and even more to still love it.

They did a 10th anniversary screening of “Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead” a few years ago, and it was so sad not to be there with Phil or Sidney. To still be here — that’s the gift. But thinking about legacy makes you start seeing yourself in the third person. You either wind up vain or bitter. No good comes from that.

Transition to more character work

The last 10 years have been a slow transition into more character acting. When I was younger, I was playing variations on a theme in every performance. That changed when I played John Brown, and even before that with Chet Baker in “Born to Be Blue,” as well as in smaller films like “Maudie” and “The Magnificent Seven.” Those were steps toward doing what people call character work. This performance let me do that kind of work in a leading role, which was exciting.

Wearing many different hats in screen career

You can’t plan that — it’s just my personality. When I was younger, I got in trouble for it. I’m one of those people who runs before he walks. I started writing before I knew how to write or had any real right to do it, but I loved it. I was worried about the longevity of an actor’s life — I saw so many people fade out — so I wanted other passions.

It’s helped me stay curious. I’ve made documentaries, written graphic novels and songs — something about that keeps me in touch with the person I was when I started acting. You want to hold on to that childlike love of the craft. The first time you go to a film festival, it feels magical. The fifth time, you’re complaining about the hotel. So you have to keep reconnecting with that younger self who saw it all as magic.

For me, doing different things keeps me thinking like a kid, like a student. That feeds back into acting. Even on “Blue Moon,” I asked myself, “What if this were my first role?”

Working with Andrew Scott?

We do some sparring in the film. I saw him do “Hamlet” about 15 years ago, and I remember saving the program and writing his name down in my journal because I thought, “This guy is amazing.” I didn’t know who he was — I might’ve just had a few hours to kill that day — but I’ve followed his career ever since.

Rick is so much like Sidney Lumet in that he cannot not rehearse. He doesn’t see rehearsal as getting ready to make the movie — it is the movie. He asked for five weeks of rehearsal, and some actors were like, “I only have five scenes, do I really need to come?” But for Rick, that’s non-negotiable. It’s where creativity happens.

Andrew loved that process. He’s a creature of the theater. We had these long, 12-page scenes — those aren’t hard for him. He’d just finished doing a one-man Chekhov show. The guy can do anything. He was a natural fit in our band.

Grueling day of shooting?

We had this huge seven-page scene, just the two of us. We were walking up and down a stairwell, fighting and crying, trying to put a 25-year friendship into one scene. It was hard — figuring out the rhythm, the pauses, the anger, the music of it all.

At the end of the day, I checked my phone — I leave it in my dressing room when I’m shooting — and my wife had texted me, “Make sure you congratulate Andrew.” I asked, “For what?” He’d just gotten 19 Emmy nominations. I went to his dressing room and said, “Hey, congratulations.” He just said, “Thanks.” That was it. He never mentioned it, never stopped working, never picked up his phone. I went home thinking, “Wow, he really fits in this troupe.”

Sony Pictures Classics and state of adult cinema?

Michael Barker and Tom Bernard at Sony Pictures Classics — their commitment is staggering. If you know them, you know how hard it is. For every “Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon” they release, they’re making dangerous bets all the time.

I never get mad at studio executives. I understand that they can be fired if the movie doesn’t make money. We have different definitions of success. For me, success is longevity. The biggest award I could ever get was seeing full-page spread on the 25th anniversary of “Before Sunrise” in the NY Times. Nobody cared that much when it came out. Now people still talk about it.

I was in a car with Michael Barker the other day, and he was nerding out about a couple of shots that were wrong in a movie I did six years ago. I just thought, “Wow, this guy really cares.”

He bought “Slacker” all those years ago, and here I am 30 years later with another Linklater movie. His commitment to finding new voices and championing filmmakers from all over the world is rare. If all you give people is hamburgers, they’ll eat hamburgers — and that’s fine; hamburgers are good — but if you offer them something else, they’ll discover they like that too. If you don’t make “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest” available, how will people ever know how great it is?

First Oscar nomination for “Training Day”

The world was a little different then. I didn’t even know nominations were coming out that morning. I took my 4-year-old daughter, Maya Hawke, to preschool. Her teacher, Odette, came up to me with tears in her eyes and said, “You’ve been nominated for an Oscar.”

I wasn’t sure I believed her. I went home and saw it on CNN. It was surreal. I had a dentist appointment that morning — and if you know me, you know I don’t go to the dentist much — and I used it as excuse to skip it. Then Denzel called and said, “You know why I’m so happy you were nominated? If you got nominated, it means people saw the movie. And if people saw the movie, I’m going to win.”

What did Denzel say after losing that night?

Denzel said to me, “Don’t worry, you don’t want to win it yet. It’ll mean so much more later.” He was right.

Philip Seymour Hoffman used to say the two hardest things in our work are failure and success. Failure can destroy you, but success can be just as tough. Phil was the first of my generation to win an Oscar, and he absolutely deserved it. Watching one of your contemporaries become fully mature artist — it’s inspiring, but it also shows how fame and praise can affect your self-esteem and ego. It’s why success can be so hard for young people — it can kill your drive early on.

The answer I usually give is that the three films feel complete. The first one begins with us on a train listening to a couple in their mid-40s fighting, and in the third one, we’ve become that couple. The circle feels complete.

If we were to do another, it might not be a “Before” film. It could be something new — maybe the “After” series. But part of what made those movies special is that Julie, Rick, and I were always in sync about what we wanted to say. That could happen again one day — it might start with one phone call or an email. But we don’t want to outlive our fan base.

AI actors like Tilly Norwood?

This is what we’re all living through — the fear of automation in every field. It’s an existential crisis. We’re slowly ceding our humanity in the name of efficiency.

I have this huge painting in my house that my daughter’s kindergarten class made of Sun Ra. It’s beautiful. A computer could make a “better” version of it — more accurate, more efficient — but it wouldn’t have been made by people I know, with love and time and imperfection.

When someone writes a song or paints something, we witness their humanity. This obsession with efficiency and greed — that’s what’s driving AI. Pretty soon, we’ll see a new movie starring James Dean, but it won’t mean anything.

Part of the joy of art is connection — the desire to communicate, to share time and emotion with another human being. Art isn’t about perfection. It’s about the messy, flawed, beautiful process of making something real.

Working with Robin Williams on “Dead Poets Society”

What we love about that movie — and movies in general — is the scratchy, sweaty stuff of real people. We like to see the hard work. That’s what connects us.