Tarantino’s ninth feature, Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood, is a brazenly entertaining, playfully self-reflexive, deeply personal movie. As such, it serves as the director’s unabashedly nostalgic love letter to the film industry–and to Los Angeles itself–at a crucial time, when major changes were about to take place, in and out tinsel town.

Our grade: A- (**** out of *****)

It’s 25 years ago to the day (May 21, 1994!) since Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction world premiered at Cannes Fest and won the top prize, the Palme d’Or, before heading to Oscar glory and cult status. Bound to be embraced by critics and viewers, Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood should be a commercial triumph, when Sony releases the picture on July 26.

Last night, I attended the world premiere of this movie, easily the most eagerly awaited event at the 2019 Cannes Film Fest, which got a much needed injection of energy and enthusiasm. Rapturously received by its first public audience, the movie got a six-minute standing ovation, the longest at this year’s edition.

I think Tarantino has made a mistake by claiming that he would only make 10 (or so) movies, as critics and journalists are now rushing to overanalyze the presumably penultimate picture as a career summation (posing the question of, is it a masterpiece or not?). For me, the most significant fact is that, after a decade or so, the lavishly skilled auteur is again working at the top of his form. (I liked in moderation Django Unchained in 2012, and was mixed-to-negative in my reaction to Hateful Eight in 2015).

It is important to place Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood in the broader context of Tarantino’s career by pointing out some thematic and similarities and differences between the new work and the previous ones.

Aptly titled, Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood not only pays homage to one of Tarantino’s idols, Sergio Leone, master of Spaghetti Westerns, who has made two films with similar titles, Once Upon a Time in the West (1968) and Once Upon a Time in America (1984), both masterpieces. There are other references to the late Italian masestro in the plot itself. Among other things, Tarantino laments the decline of the Western–the genre’s heroes and anti-hero, and the actors and stuntmen who play them–on both the big and the small screen; after all, 1969 saw the release of Peckinpah’s most influential Western, The Wild Bunch.

The film’s narrative structure is divided into three parts, which are almost equal in duration. The tale begins on Saturday, Februray 8, 1969, then moves on to Sunday, February 9, 1969, and it culminates six months later, on August 8, 1969. The first two thirds of the film–which has a running time of 160 minutes (by my watch)–are far more interesting than the third in both plot and characterization.

Last week, Tarantino had posted a letter to Cannes audiences, saying the festival was all about “discovering a story for the first time,” asking that “everyone avoids revealing anything that would prevent later audiences from experiencing the film in the same way.” No spoilers then. When you see the picture–and its unpredictable (if not entirely satisfying) ending–you will understand his reasoning.

Suffice is to say that while using as background the Manson Family murders of Sharon Tate, her unborn child and four others in August 1969, Tarantino does not claim or aim to offer his personal perspective on those painful events. Those tragedies truly signaled the end of an era, which saw the end of the hippie dream, the soon to take place Woodstock Festival, not to mention the cumulative effect of the political assassinations.

Born in 1963, Tarantino would have been six-years-old at the time, and I can only speculate what exactly he remembers now of that era. Even so, what’s beyond doubt is the profound impact of that period and its subcultures on him as a future filmmaker and dedicated Angelino. Early on, Dalton observes, “in Los Angeles, you don’t rent an apartment, you don’t pass through, you buy a house.”

Though billed as an ensemble piece–there are many famous actors in cameo roles–Once Upon a Time is essentially a two-handler, a tale of two male characters and the deep, if also shifting, bond between them. Tarantino is in the good company of John Ford, Peckinpah, and other directors of westerns in celebrating male camaraderie–its ups and downs, but never shaky friendship.

DiCaprio is well cast as Rick Dalton, a second-rate Western and action actor, who’s popular on TV as a cowboy bounty hunter, but not doing so well in the movies. He’s beginning to feel his age, drinks too hard, doesn’t not always remember his lines. He’s rapidly losing his self-confidence, especially after his agent tells him “It’s bad for your image to always be the one who gets thumped.” That the agent is played by Al Pacino, who has a resonant, long scene in the opening sequence, and then a second, shorter one later on, brings an extra dimension of reflexivity and intertextuality.

Like other aging actors, Dalton refuses to slow down, hanging on to his upscale lifestyle in a lavish mansion in Hollywood Hills (on Cielo Drive, my neighborhood…), spending time at his pool, making frozen margaritas at midnight, and of course, watching his own old shows on TV.

The most enjoyable scenes of the film, which on one level is a classic Hollywood male buddy movie, describe the camaraderie and co-dependency between Dalton and his stuntman, Cliff Booth (magnificently played by Brad Pitt). Booth is not just Dalton’s double, he’s also a driver, a sidekick, a companion, and, most important of all, a close friend; in fact, he’s the only man Dalton can rely on, blindly. The invisible narrator describes Booth as “more than a brother and a little less than a wife.”

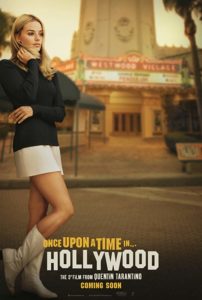

It “just happens” that Dalton lives next door to Polish director Roman Polanski and his newly wed wife, the sexy up-and-coming actress Sharon Tate (Margot Robbie); in real-life, the couple married in 1968, just when Polanski was becoming a hot Hollywood director (Rosemary’s Baby was released June 12, 1968).

As a writer, Tarantino does a good balancing act of allowing each of two men to display the distinctive traits of their characters–and their subjective strengths as both vet actors and glamorous movie stars.

DiCaprio, who finally had won the Best Oscar for The Revenant, has demonstrated his considerable dramatic skills in many films, and here he gets to add some new facets, not just in his big boozing scenes, in which he loses it, but also when he sobs in public and private–defying the motto “real men don’t cry”–and the scene in which he admits, “officially, I’m a has-been.” There’s a good deal of self-irony in the fact that Dalton often gives stronger, more authentic performances in his trailer than on the set.

To me, the movie’s biggest surprise is Brad Pitt’s performance, which, with some justice, should lend him a Best Actor Oscar nomination (it would be his fourth nod). Displaying his handsome face and muscular body, Pitt, impressively underacting, renders an astonishingly laconic turn as the infallibly cool, ultra-confident man, always ready to meet his competitors and challengers.

Pitt gets at least three priceless sequences, the best of which may be the one in which he clobbers the vainly arrogant Bruce Lee (Mike Moh) round the back of the set. (Two of these scenes got loud applause during the premiere).

In many other scenes, Booth is seen driving, dropping Dalton at his place, or by himself, with blasting music on his radio, relishing the various vistas of Los Angeles. There’s a good, inside-joke, when Tarantino shows numerous movie theaters displaying kitschy and preposterous marquees and posters of their B-movies (the take is set decades before the DVD and Streaming Revolutions).

There are no significant women in either man’s lives. We are led to believe that Booth somehow got away with killing his wife (a brief flashback to a yacht is referencing the death of Natalie Wood in 1981). Happy and self-satisfied, he now lives in a trailer with his buddy, a loyal Doberman called Brandy. His daily routine involves chatting with his dog and cooking for him (I wish I could describe those meals in greater detail).

Mid-way, Dalton is making a new Western, and Tarantino, an admirer of the genre, shows a sizeable sequence of that Western itself. There are also parodies of Hollywood WWII movies–a la Tarantino’s 2009’s Inglourious Basterds. In one, Dalton incinerates the entire Nazi leadership with a flamethrower, an old-fashioned tool machine that would become handy later on in Dalton’s “real” life.

Of the three main characters, the Sharon Tate’s is the least developed, which is a shame for Robbie is very good actress. She’s introduced as a sexy, fluffy, wanna-be-serious actress, wearing tight shorts and knee-high white boots. In what’s her only big scene, Tate is going to the movies by herself, avoiding paying for the ticket by claiming she is the real Tate, acting in the movie. With a big, naïve grin on her face, she’s watching her own silly turn in a minor comedy, The Wrecking Crew, starring Dean Martin. There are few customers in the audience, but Tate joyously relishes their reaction when she is onscreen. For a brief, magical moment, Robbie the actress, Tate the spectator, and Tate the actress playing a part in Wrecking Crew, blend into one human being.

(Tarantino has done his homework: Released in February 1969, the spy-comedy is the fourth and final film in which Martin played Matt Helm, alongside four beautiful girls, Tate, Elke Sommer, Nancy Kwan and Tina Louise).

As Booth drives around, often taking the same route to his home, next to a Van Nuys Drive-In), he keeps spotting pretty girls from the Manson cult. One flirtatiously seductive girl, “Pussy Cat” (Margaret Qualley), who claims to be 18, responds to his look, and he invites her into his car, taking her back to a remote ranch, formerly used for shooting Westerns.

Tarantino demonstrates his bravura mise-en-scene skills in what’s the film’s most scary and suspenseful scene, when Booth insists on seeing the ranch’s leader–despite strong objections from its residents. Unfazed and in defiance, Booth walks though one shabby room after another until he encounters its owner, George Spahn (Bruce Dern), an old colleague of his who doesn’t recognize him. George turns out to be a cranky old man, unable to remember or see anything; the girls, who both protect and exploit him, later claim that “George is not blind.”

The last segment preapres us for the specific and ominous timeline of the fateful day–in reality, it’ the night Tate and friends was murdered. Like Hitchcok in Psycho and other directors, Tarantino places the precise time–Saturday 10:33 pm or 12:01 am–in yellow numbers on screen to denote what each of the main characters was doing (Booth was walking out his dog).

Taking the same flight (albeit if different classes), Dalton and Booth return home after making four spaghetti Westerns in Italy by the second-best director of such stuff. It’s at this point that the movie gets elegiac, but not sentimental. Using frequent lines from film noir–“It’s the end of the road! It’s the end of the line!” Dalton tells Booth that he can no longer afford to pay him. Dalton comes back with a new wife, an Italian starlet Francesca Capucci. No tears are shed, and the buddies decide to celebrate by getting royally drunk together.

At the same time, Tate and friends spend what’s announced as the hottest day of the summer at the iconic Mexican restaurant El Coyote (on Beverley Blvd).

Last Scene (Spoiler Alert):

In the evening of August 8, 1969, their first day back in L.A. Dalton and Booth go out to commemorate their time working together and then return to Dalton’s house. Tate and Sebring go out for dinner with friends and then return to her house. All the characters are in the same location, at El Cielo Drive.

Booth smokes an acidcigarette given to him by Pussycat and takes Brandy for a walk while Dalton prepares drinks. Manson Family members Tex, Sadie, Flowerchild and Katie arrive, planning to murder Tate and her friends.

Dalton hears the car and orders them to get off his street. Changing plans, the Manson members decide to instead kill Dalton. Sadie reasons that Hollywood has “taught them to murder.” “If you grew up watching TV, you grew up watching murder–my idea is to kill the people who taught us to kill!” she says, “Let’s kill some piggies!” Flowerchild deserts the group, speeding off with their car, leaving her amigos to their own devices.

They break into Dalton’s house and confront Capucci and Booth, who recognizes them from his earlier visit to Spahn Ranch. Booth orders Brandy to attack, and together they kill Katie and Tex and injure Sadie. Booth is stabbed and knocked unconscious in the altercation. Sadie stumbles outside, alarming Dalton, who is in his pool listening to music, oblivious to the mayhem. Dalton retrieves a flamethrower previously used in a movie and incinerates Sadie.

The climax is deliberately and radically cartoonish, and sensationally violent–in the best tradition of Tarantino’s earlier work, sort of telling his fans, ‘I’m still the Tarantino of Reservoir Dogs and Pulp Fiction.

Booth, injured, is taken by ambulance to the hospital to treat his wounds. Sebring engages Dalton in some small talk outside, and after slight hesitation, he accepts an invitation to have drinks with Tate and company.

Each of the film’s three parts (this is my division) is marked by a different tone and rhythm as befits the structure, which is multi-layered, at times with flashbacks within flashbacks.

The film is not flawless. Admittedly, there are some scenes that are too-leisurely paced, and one or two that are just flat. Moreover, there are structural devices that are inconsistent, occasionally used, and then dropped. For example, there’s a brief voiceover narration that depicts Dalton’s work in Italy and the state of his career and mind afterwards.

Cast

Leonardo DiCaprio as Rick Dalton

Brad Pitt as Cliff Booth

Margot Robbie as Sharon Tate

Emile Hirsch as Jay Sebring

Margaret Qualley as “Pussycat”

Timothy Olyphant as James Stacy

Julia Butters as Trudi Fraser

Austin Butler as “Tex”

Dakota Fanning as “Squeaky”

Bruce Dern as George Spahn

Mike Moh as Bruce Lee

Luke Perry as Wayne Maunder

Damian Lewis as Steve McQueen

Al Pacino as Marvin Schwarz

Nicholas Hammond as Sam Wanamaker

Samantha Robinson as Abigail Folger

Rafał Zawierucha as Roman Polanski

Lorenza Izzo as Francesca Capucci