Repulsion, Roman Polanski’s first English-speaking film, is one of his two or three masterpieces, a fully realized, painstaking detailed, emotionally haunting work that benefits from the stunning performance of French actress Catherine Deneuve, then only 21 and known for her great, photogenic beauty rather than dramatic chops.

B+ (**** out of *****)

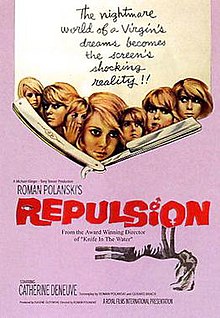

| Repulsion | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster

|

|

Shot in black-and-white, this horror drama about the emotional and mental disintegration of a lonely, frigid woman, is scary, disturbing, and replete of ideas and images about sexual repression and panic anxiety that would recur in Polanski’s future works.

Deneuve plays Carol, a quiet and shy beautician who works in South Kensington, London, and lives nearby with her older sister, Helen (Yvonne Furneaux). Just the mere presence of Helen’s aggressive beau Michael repels Carol, not to mention his disgusting habit f leaving his razor lying around in the bathroom. Late at night, lying silently in her bed, Carol listens to the noises produced by Helen and Michael’s lovemaking.

Withdrawn since childhood, Carol is unable to have normal relationship (or communication) with men. Both sisters are isolated for the very fact that they are foreigners living in not a particular friendly city.

Carol’s existence is defined by dull routines, such as unfulfilling work at the beauty parlor, during which she often experiences moments of abstraction, distraction, and passivity for which she’s reproached by her female boss. She takes her lunch alone in a small café, where she attracts the attention of men, including Colin (John Fraser), a rather sympathetic and persistent man who wants to date her.

Carol is repelled and terrified by men, all men. When the handsome Colin, infatuated and then obsessed with her look, kisses Carol faintly, she frantically rushes to her room to brush her teeth. Walking back to her apartment, she’s subjected to rude whistles by road workers, which she ignores.

When Helen announces that she and Michael are taking off on a holiday to Italy, Carol is terrified like an abandoned child, begging her sister not to go; we get the feeling that this is perhaps the first time in her life she would be left alone. During the two-week absence of her sister, the apartment, shabby in the first place, becomes a shambles, a junkyard with leftover food, objects lying on the floor, and so on. Gradually, Carol’s physical and social isolation in a confined apartment escalate to the point of no escape, unleashing her built up panic and terror with acts of violence.

Two males manage to intrude into Carol’s increasingly isolated life, the concerned Colin who breaks into the apartment, and the landlord (Patrick Wymark), who uses his own key in an effort to collect the long overdue rent. Needless to say, neither leaves the place.

The film’s foreboding mood begins right away with the credits, which are accompanied by ominous drumbeats, before revealing a close-up of Carol’s face, centering on her eyes. The next image reveals a mature woman in an upper-class beauty salon, whose face is covered with white cream, giving the impression of a corpse.

The horror emerges not from outside threats but from within the subjective mind of Carol. To his credit, Polnaski doesn’t treat her as a type or clinical case study, but as a particular woman living in a particular milieu, suffering from subjective nightmares and hallucinations.

Early on a reference is made to a crack in the plasterwork of the kitchen wall, and we know it’s only a matter of time before Helen would be seeing other cracks. Using sharp, high-angle shots, it often seems as if the ceilings are looking at Carol. Polanksi’s restless camera tracks around the apartment, registering minute details, all of which later feature prominently in the plot.

Almost every detail or image counts, such a recurrent shot of an old family photo, which is revelatory in meaning. In it, we observe Helen as a child leaning against her father’s knee, while youngster sister Carol stands a little aloof, staring away from the family.

The movie offers in great and careful detail the mind of a woman, who disintegrated under strains of paranoia and alienation, descending into sheer madness.

Deneuve, who is in nearly every scene, gives a stunning performance, particularly during the silent sequences, in which she lies in bed and just stares at the walls and listens to the sounds of silence. In a state of paranoid delusion, she sees hands clutching at her through the walls, and imagines hairy, aggressive, unappealing men lying with her under her bed covers.

Reel/Real Impact

In Roman Polanski’s second feature, Catherine Deneuve plays Carol, young, absent-minded blond, a foreign-born manicurist living alone in London. She’s a woman who retreats into a squalid little apartment in London. But even that space doesn’t feel safe, as the walls crack and ooze, seemingly reaching out to grope her.

The first jolt comes when Carol shuts the closet door and, for a split second, sees the shadow of a man reflected in its mirror. Later, she imagines someone assaulting her in bed. Can her visions be trusted?

The unraveling of Carol’s troubled mind would influence numerous hallucinatory horror imitations, such as “The Babadook” to “Black Swan.”

Cast:

Carol (Catherine Deneuve)

Michael (Ian Hendry)

Colin (John Fraser)

The Landlord (Patrick Wymark)

Helen (Yvonne Furneaux)

John (James Villiers)

Credits

Directed by Roman Polanski

Screenplay by Polanski, Gérard Brach, David Stone

Story by Polanski and Brach

Produced by Gene Gutowski

Cinematography Gilbert Taylor

Edited by Alastair McIntyre

Music by Chico Hamilton

Production companies Compton Films; Tekli British Productions

Distributed by Compton Films

Release date: June 10, 1965 (UK)

Running time: 105 minutes

Budget £65,000

Box office $3.1 million