“Picnic” was one of the artistic highlights and box-office hits of 1955, one of the best years in Hollywood’s history.

“Picnic” was one of the artistic highlights and box-office hits of 1955, one of the best years in Hollywood’s history.“Picnic” is one of those rare works, a film that captures vividly the cultural essence, the collective dreams and anxieties of the whole decade.

Opening on Broadway on February 19, 1953, “Picnic” ran for 477 performances. It was singled out as the best American play by the New York Drama Critics Circle, and won the 1953 Pulitzer Prize for Drama. The stage production became famous for another reason: It featured the Broadway debut of Paul Newman before heading to Hollywood and pursuing a glorious screen career that continues at present.

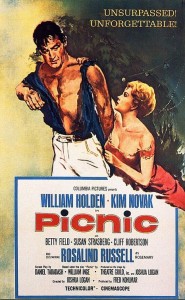

Joshua Logan’s film version was nominated for five Academy Awards, including Best Picture; the Oscar winner was “Marty.” The movie won two Awards: Color Art Direction and Set Decoration (William Flannery, Jo Mielziner, and Robert Priestly), and Editing (Charles Nelson and William A. Lyon). “Picnic” is the movie that made Kim Novak a certifiable film star, and the film that persuaded Hitchcock to cast her in “Vertigo,” three years later.

The movie employs thematic conventions that highlight the ideological context and subtext of the l950s. The narrative begins on Labor Day, thus indicating it’s a special, not routine, day. Hal Carter (William Holden), a good-looking guy jumps from a freight train in a small town in the Kansas plains. A college dropout, Carter is not a bad guy, but a bum, a man who has been searching but has not been able to find himself. Carter has been drifting from one job to another (including the Army), and from one town to another ever since he was kicked out of college, where he was admitted on an athletic (football) scholarship.

A brief period in Hollywood and a screen test proved he was going to have “a “big career” with a promising screen name, Brush Carter. (Tennessee Williams used the same type of man in “Sweet Bird of Youth”). But “they were going to have to pull out all my teeth and get me new ones, so naturally I refused.” Hal was arrested by the police, after hitchhiking in a car driven by women who wanted to party, then robbed him. “I’m telling you, women are gettin’ desperate,” says Hal, who flash-forwards in one sentence the movie’s chief issue: Desperate women.

Hal hopes that his best friend from college, Alan Benson (Cliff Robertson), heir of the town’s richest family, will help him find a job. Hal is an outsider who wants to become an insider, a man wishing to settle down and live a respectable middle-class life.

The bulk of the narrative deals with how this stud sets in motion an inevitable chain of events, events that have shattering effects on the town’s residents, forever altering their lives. “Picnic” is a woman’s film, heavily populated by female characters. There are five women, each representing a social type. Mother Flo (Betty Field) is a middle-aged woman who hates Hal, because he reminds her of her swaggering husband who, years back, had deserted her, leaving her the responsibility of raising two girls. Her dream now is to marry off her daughter to Benson, perceiving marriage as her daughter’s only avenue for upward mobility. Madge (Kim Novak), her eldest daughter and “prettiest girl in town,” is sensitive, but not too bright. Millie (Susan Strasberg), the younger daughter, is a precocious tomboy, the bookish type Mrs. Helen Potts (Verna Felton) is the Owens’s next-door neighbor, a middle-aged woman living with her sickly mother. She too has no man in her life.

Rosemary Sidney (Rosalind Russell), a high school teacher, is a spinster who rents a furnished room at the Owens’s house. Rosemary introduces herself with the following line: “Anybody mind if an old maid school teacher joins the company” A bit neurotic, she makes her last desperate grab at a marital bliss, fearing life might be passing her by. Anxious to get married, she is willing to compromise and take Howard (Arthur O’Connell), a dull and selfish traveling salesman. But so far Howard has been “just a friend-boy, not a fay friend.” Her hysterical preparations for their meeting reduce her to a teenage girl waiting for her first date. She expects, by her old-fashioned morality, to be treated as a lady. By standards of dominant culture, until married, Rosemary is a failure.

Unlike teachers in small-town films, Rosemary is not concerned with her career or her students’ education; she is never seen in a classroom. Obsessed with singlehood, she would give up her profession as soon as she gets married. Rosemary also represents conservative ethics, reproaching Mother Flo for letting her daughter read “filthy” books, such as “The Ballad of the Sad Cafe,” a book, she says, “many wanted banned from the public library.” The introduction of each character is a field day for semiologists. Each of the five women is associated with an object which signifies her respective concerns: Mrs. Potts is holding a cake; Mother Flo is seen in the kitchen with eggs; Rosemary uses cream for her wrinkles; Madge carries a hair dryer (a phallic object); Millie is reading a book. In their first conversation, Millie says to Madge, “Dry your silly hair over somebody else,” to which the latter replies, “Why don’t you read your silly book under somebody else” Mother Flo is horrified when Madge says, “I wish it didn’t take so long to dry–I think one summer I’ll cut it short.” Madge’s hair is the symbol of her beauty and her best asset as a woman.

The three men in Picnic also represent types, associated with different activities: Alan likes to play gulf; Hal, to work outdoors; and Howard, the salesman, to drink. Stripped to his waist for most of the film, Hal is an outdoor man who feels more comfortable in Nature, by the river, far from the public eye. When Mrs. Potts offers to wash his dirty shirt, he wonders if “anybody’d mind’ “Of course not,” says Mrs. Potts, “You’re a man, what’s the difference” But there is a difference, and for the rest of the story he is shirtless. Early on, Rosemary describes him as “naked as an Indian,” revealing at once her sexual starvation and racial biases. “Who does he think is interested” she asks, but she–and the other repressed women–are interested in him.

In the film’s troubling dramatic climax, Rosemary, her inhibitions down (after a couple of drinks), makes a pass at Hal and is brutally rejected by him. Forcing him to dance with her, she tears his shirt; now he is naked. “You won’t stay younger forever,” says the vengeful Rosemary, “did ya ever think that What’ll become of you then” (Geraldine Page uses almost the same words in Sweet Bird of Youth, in a similar scene with her stud, Paul Newman). Hal is an uninhibited spirit, as Mrs. Potts says after his departure: “He clumped through the house like he was still outdoors. You knew there was a man in the house!” Hal and Alan complement each other: each admires the attributes of the other. Their names, Hal and Alan, are also similar. Hal was the physical type in school, excelling in football and chasing girls. Alan, the rich kid who excelled in academic studies, has always been envious of Hal’s ease and success with women.

Each of the five women represents a different ideological stance toward love and marriage, demonstrating the inherent tension between the two values. The commonsensical Mrs. Potts believes in the superiority of feelings over reason. She is the only woman to give her blessings to Madge and Hal’s romance from the start. Rosemary knows that marriage, even an unhappy one, will redeem her from her inferior status as spinster; a compromising (unsatisfactory) marriage is better than no marriage.

Mother Flo is also more pragmatic than romantic, perceiving marriage as an economic transaction, an arrangement in which Madge’s youth and beauty would be exchanged for Alan’s economic security and prestige. “A pretty girl doesn’t have long,” she tells Madge, “Just a few years.” But once married, she’ll be “the equal of kings…she can walk out of a shanty like this and live in a palace.” However, if she “loses her chance when she’s young, she might as well throw all her prettiness away.” Protesting that she is only nineteen, Mother Flo tells Madge: “And next summer you’ll be twenty, and then twenty one, and then forty!”

The town is ruled by the Bensons, owners of the vast grain operations. Alan tells Madge that his father is “impressed with winning,” referring to her crowning as the Beauty Queen, and “with people making the most of money.” Having the right connections makes a difference, as one resident tells Hal, “the governor’s an old side-kick of mine. That’s how I got the job.” The class structure is also obvious: The Owens reside on the other side of the tracks. When a working-class boy, Bomber, courts Madge, he expresses his slight jealousy, saying he saw her riding around in Alan’s Convertible, “like you was a Duchess.”

The film’s coda provides a resolution to its dramatic conflict, celebrating romantic love over pragmatic marriage. Mother Flo pleads with Madge to stay in town, claiming that her passionate love is transitory, that Hal is good for nothing, a man who would drink and be unfaithful to her. But Madge is determined to leave town and, as Hal jumps on train, she boards a bus to Tulsa.

Audiences at the time saw it as happy ending, but viewed from today’s perspective, this closure is ambiguous. Will Madege follow in her mother’s footsteps Weighing her alternatives, living in a repressive and boring town versus an unknown but potentially exciting future, has Madge made the right choice. (The original ending was even more ambivalent, and preview audiences expressed dislike for its “negativity” and “inconclusiveness”)

The scholar Michael Wood pointed out that the film’s “persistent, insidious hysteria,” and its “undercurrent of alienation and loneliness,” were unnoticed at the time. Indeed, more than anything else, Picnic is about repressed sexuality and its corresponding price. No woman in the film is fulfilled, sexually or emotionally: There are either no men, or no desirable men in their lives. Hal is the only desirable male, a stud surrounded by sex-starved women.