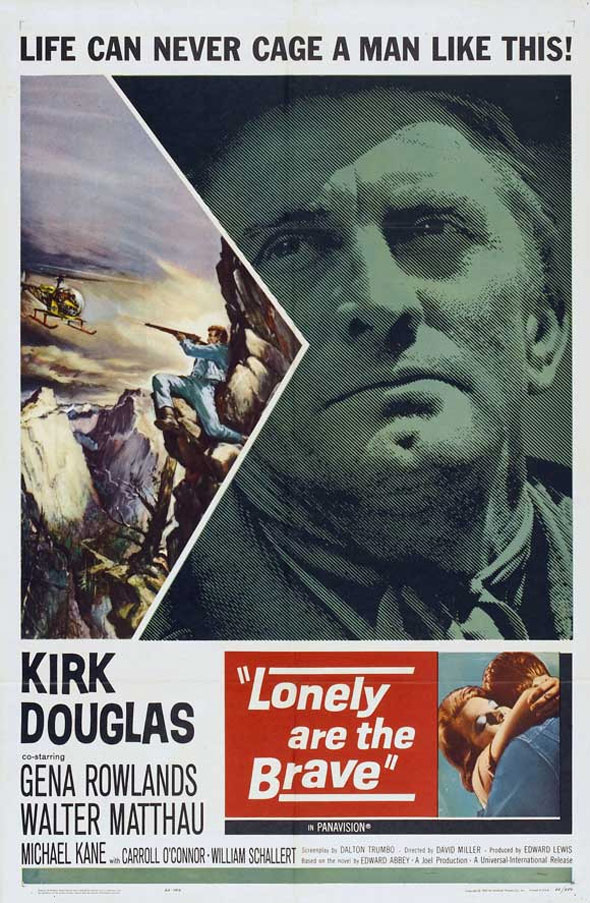

Kirk Douglas produced and starred in Lonely Are the Brave, David Miller’s elegiac Western, lamenting the vanishing of the Old West and its breed of heroes and ethical mores.

Pleased with the work of the then blacklisted Dalton Trumbo on his 1960 epic Spartacus, which was both a critical and commercial hit, Douglas hired him again.

As scripted by Dalton Trumbo, the movie deals with the wish and effort to maintain one’s individuality in an increasingly technology and bureaucracy-dominated world, showing suspicion and contempt for the rigidly organized society, and admiration for the old values of chivalry, manhood, and self-respect.

Essentially downbeat, “Lonely Are the Brave” tells the story of a cowboy named Jack Burns (Douglas), who’s trying to live by his own code of ethics, struggling not to buckle down to or be defeated by “civilization,” but eventually succumbing and beaten by it.

Needless to say, despite critical acclaim, the movie was not a box-office success. Douglas blamed the studio for its mode of release, regarding the Western as an art film (which it was). But it could be that the Western’s downbeat tone and ambiguous closure also were responsible for lack of broad appeal

Some critics drew a parallel between Kirk Douglas and the loner cowboy he played. A maverick movie star, Douglas was known for his independence and aversion for abiding studio contracts, initiating and often producing his own film projects (such as “Spartacus” in 1960).

Based on the novel “Brave Cowboy” by Edward Abbey, Trumbo’s script concerns a man’s plight in an increasingly mechanized world, juxtaposing the beloved figure of the lone American cowboy, roaming the spacious West with the company of his horse (his best friend) with a bureaucratic sheriff and other representatives of the law.

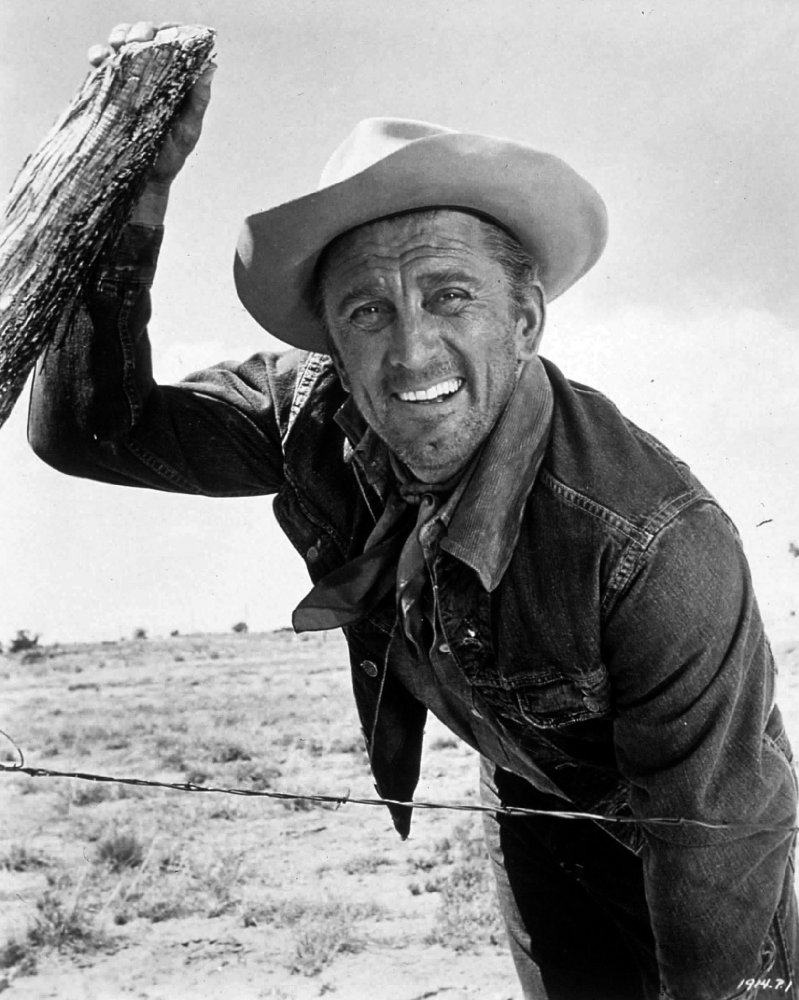

The tale opens with a relaxed and smiling Burns, resting in the empty vast landscape, seemingly content with his life and freedom. The peaceful atmosphere is then sharply interrupted by the roar of a jet plane, which gets an indifferent look from the cowboy, suggesting that it has no significance for him.

Burns stops by the Bondis in nearby Albuquerque, where he finds out from Jerri (Gena Rowlands) that her husband and his friend Paul (Michael Kanes) had been jailed for helping illegal Mexicans enter into the U.S.

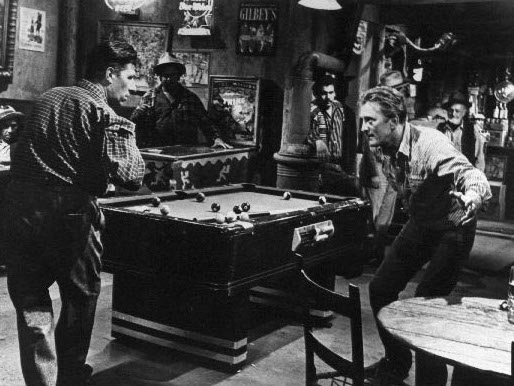

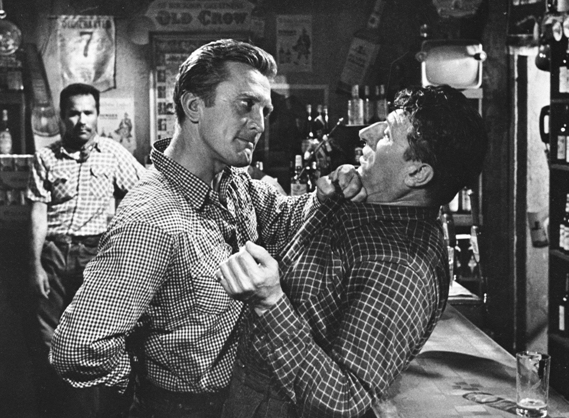

To get himself arrested and thrown into prison so that he can help free his friend in a breakout, Burns starts a brawl in a saloon. However, in jail, Bondi tells Bondi that he wants to serve his time and get out legitimately, instead of being fugitive for the rest of his life. Hurt but undaunted, Burns breaks out himself and heads for the hills, pursued by a compassionate technocratic sheriff, his posse, and his helicopters.

The message of Trambo’s scenario, adapted from Edward Abbey’s novel “The Brave Cowboy,” is occasionally too overstated by heavy reliance on symbols and metaphors. For example, Burns and his horse are seen crossing the over-crammed highway, filled with numerous, impersonal vehicles.

As noted, Douglas, a rebellious, individualistic actor, identified completely with the role, which lends credibility to his performance. You believe Douglas when he explains to Jerry what a loner is: “A loner is a born cripple. He’s a cripple because the only person he can live with is himself. It’s his life, the way he wants to live. It’s all for him. A guy like that, he’d kill a woman like you. Because he couldn’t love you, not the way you are loved.”

In a later speech, he sums up both the myth and reality of the West as the last frontier: “A westerner likes open country. That means he’s got to hate fences. And the more fences there are, the more he hates them. Have you ever noticed how many fences there’re getting to be? And the signs they got on them: no hunting, no hiking, no admission, no trespassing, private property, closed area, start moving, go away, get lost, drop dead!

The film is splendidly acted by the cast, particularly Douglas as the cowboy who will not yield to the modern world and its notion of progress, attempting to hold on as long as he can to his dream of freedom and the pioneering spirit.

Walter Matthau, then playing mostly supporting parts, is also good as the sensitive sheriff who doesn’t really want to capture Burns.

Playing a truck driver was one of the first screen roles of Carroll O’Connor, who would become a popular TV star in the long-running series, All in the Family.

This is the most accomplished film of David Miller, who directs with eloquent feeling for landscape and attention to character. His other well-known movies include the Joan Crawford noir melodrama “Sudden Fear,” and the box-office hit thriller “Midnight Lace,” starring Rex Harrison and Doris Day.

Production values are impressive, particularly Philip Lathrop black-and-white cinematography and Jerry Goldsmith’s evocative score.

It is worth noting that the year of 1962 saw the release of another black-and-white elegiac Western, John Ford’s masterful The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, which contrasted the mores of the Old West with those of the New West via the casing of John Wayne and Jimmy Stewart.

President Kennedy watched the movie in the White House in November 1962. In his 1976 memoir Conversations with Kennedy, Ben Bradlee wrote, “Jackie read off the list of what was available, and the President selected the one film we had all unanimously voted against, a brutal, sadistic little Western called Lonely Are the Brave

Cast

Jack Burns (Kirk Douglas)

Jerri Bondi (Gena Rowlands)

Sheriff Johnson (Walter Matthau)

Paul Bondi (Michael Kane)

Hinton (Carol O’Connor)

Harry (William Schallert)

Reverend Hoskins (Karl Swensen)

Gutierrez (George Kennedy)

Deputy Glynn (Dan Sheridan)

One Arm (Bill Raisch)

First Deputy (William Mims)

Old Man (Martin Garralaga)

Prisoner (Lalo Rios)

Credits

A Joel Production

Produced by Edward Lewis

Directed by David Miller

Screenplay: Dalton Trumbo, based on the novel The Brave Cowboy by Edward Abbey.

Camera: Phil Lathrop

Editing: Leon Barsha

Art direction: Alexander Golitzen and Robert E. Smith

Music: Jerry Goldsmith

Running time: 107 Minutes