Like Orson Welles’s 1942 The Magnificent Ambersons, Sam Wood’s Kings Row, released in 1943, is situated at the turn of the century, and like that picture, it takes place in a Mid-Western railroad town.

The narrative begins in 1890, then jumps to 1900, while following its characters through 1905. In the first sequence of the tale (about 13 minutes), we get a depiction of the main characters as children.

Like Hitchcock’s Shadow of a Doubt, made in the same year, Kings Row addresses the issue of the duplicity of human nature. What is different, however, is the film’s style, which is a Hollywood melodrama, compared with Magnificent’s epic scale and Shadow’s psychological thriller. Indeed, the best way to analyze Kings Row is as a melodrama marked by excessive plotting, sentimental contrivances, exaggerated emotions, improbable motivations, and catharsis through tear jerking.

The text abounds in problems of all kinds, some never treated with such explicitness on the screen before. Among other issues, the movie deals with insanity, homicide, suicide, incest, euthanasia, amputation, malpractice, and embezzlement. An uncharacteristic film of the 1940s (in tone and theme, it belongs to 1950s melodramas), it is instructive that its release was postponed by several months–it opened in February 1942–because Warners felt uncomfortable about distributing such a film shortly after Pearl Harbor. Indeed, the commercial success of Kings Row not only surpassed expectations but was a surprise. Nominated for the Best Picture Oscar, Kings Row grossed over two million dollars, a considerable amount by 1940s standards.

Casey Robinson took liberties in adapting Henry Bellamann’s novel about small-town frustrations. Fearing the impositions of the Production Code, the incestuous relationship between Dr. Tower and his daughter was changed into insanity. In the film, Dr. Tower kills his daughter, after realizing he is incapable of treating her insanity. Second, instead of the mercy killing of Parris’s grandmother, she dies of cancer. Third, in the book, Drake dies of cancer as a result of unnecessary amputation, but in the film, Drake regains faith in life due to his wife’s unbounded love and Parris’s friendship.

In the film’s opening scene, the camera travels slowly, then pauses on a road sign that says: “Kings Row. A good clean town. A good town to live in, and a good place to raise your children.” The sign is, of course, ironic for the town is anything but a good place to raise children.

The first part, the prologue, is set on a nice spring afternoon. Two children, Parris Mitchell and Cassandra Tower, are walking from school through the field, resting, and enjoying nature. The hill, with its beautiful trees and grass, would later serve as a meeting point for the protagonists, where important secrets would be exchanged and personal confessions made. Throughout the film, Nature is depicted as a place of escape from Culture’s repressions, represented by the kids’ parents.

The initial scenes establishe the crucial attributes of the dramatis personae. Parentless, Parris lives with his grandmother in the nice side of town. An upper-class kid, he plays the piano and speaks French. Cassandra’s father is the prestigious Dr. Alexander Tower (Claude Rains), whose wife is insane. Neither kid (nor the other children) has two parents; they are products of one-parent families. Parris is invited to two birthday parties on the same day: one for Louise Gordon, the other for Cassandra. The housekeeper gossips about the Tower’s “strangeness” and suggests that Parris go to the Gordon’s party, but his grandmother interrupts her sharply: “Parris will decide for himself.” The film thus cherishes the values of independent judgment. Hence, while dying of cancer, Parris’s grandmother instructs him: “You have to judge people by what you find them to be, and not by what other people say they are.” Appearances are deceptive and gossip is a vice to stay away from.

More than other movies of the 1940s, Kings Row stresses the importance of social class. Each and every character is subjectively aware of his or her class membership.

Of the five protagonists, only Randy Monoghan (Ann Sheridan) is of the working class, living in a shack on the other side of the tracks. Of Irish descent, Randy resides with her father (she has no mother) and brother, both of whom working for the railroad company. Attractive in a natural fashion, Randy is the “healthiest,” or least problematic, girl. As a youngster, she behaves like a tomboy playing with and beating the boys; as a young woman, she becomes rational and forthright.

The other, upper-middle class children are each problematic in one way or another. Cassandra Tower (Betty Field) is locked in her house by her father, who prohibits her to see anyone. She is a frightened, hysterical girl, peering behind closed doors. Her only chance of escape is to go with Parris to Vienna, but he wishes to finish his studies first. When her father finds out about her plan, he poisons her and then shoots himself.

Louise Gordon (Nancy Coleman), a pretty but frail girl, is also kept indoors by her vicious parents, Dr. Gordon (Charles Coburn) and his wife (Judith Anderson). They forbid her to go out with Drake McHugh (Ronald Reagan) because he is “wild” and beneath her class. Her abusive father uses physical force to impose his will, slapping her when she threatens to reveal who he really is.

Drake starts as a rich kid (living on inherited allowance), but moves downtown after losing his fortune in bank embezzlement. He has to start all over again, asking Randy’s father, a railroad foreman, to employ him. The film contrasts Parris and Drake as two desirable role models. Drake is the outdoor type, carefree and happy-go-lucky. He is the complete extrovert, usually seen outdoors riding his horse carriage. Parris, by contrast, is the more intellectual type, sensitive and compassionate to the needs of others. Parris teaches Drake what he needs most: spiritual strength to meet his new, painful reality (crippled, his legs were unnecessarily amputated). And Drake brings real joy to Parris’s life. They are presented as two complementary facets of ideal masculinity.

This contrast between indoor and outdoor types is consistent. With the exception of Randy, the women are placed indoors, often kept there against their will. They are withdrawn from the outside world and, by implication, from themselves. Social isolation goes hand in hand with self-estrangement and alienation. The recurrent visual motif is that of a woman standing behind closed windows, looking outside. Every house is divided into front-stage and backstage, to use Goffman’s dramaturgical terminology. Parris is asked by Dr. Tower to use the backdoor; he is not allowed to go upstairs, where Dr. Tower confines his wife (and later his daughter). Imprisoned in her own home, Louise Gordon looks forlornly through the window as Drake and his new flame, Randy, ride together in his carriage. Dr. Gordon’s brutal operations are also executed on the second floor; he looks through the window as, downstairs, the children gossip about his sadistic torture of patients.

By taking the children’s point of view, Kings Row anticipates the importance of youth culture in the l950s. With few exceptions, the villains and causes of most problems are the oppressive and insensitive parents. Moreover, no member of the established professions is portrayed favorably. The bank president is corrupt, and Dr. Gordon is engaged in malpractice; a sadist, he uses no anesthesia in his operations. Dr. Gordon’s record is bad, but there is one exception: Parris’s grandmother, whom he treats kindly because of her privileged class position.

The narrative provides an interesting view of the medical profession and the emerging field of psychiatry. Dr. Tower is a man who sacrificed his brilliant career when he settled down in Kings Row because of his wife’s insanity. Serving as a tutor to Parris (whom he regards as surrogate son), he prepares him for medical school. “Do you want to be a good doctor or one of these country quacks (the imminent carpenter)” asks Tower.

Like the hero of John Ford’s Arrowsmith, Parris wants to be a doctor like “those you read in books, the legendary sort of doctor.” Dr. Tower’s approach to medicine is “a game in which man pits his brain against the forces of destruction and disease.”

Psychiatry is a new, intriguing field, and the film acknowledges the influence of Freud and psychoanalysis on American culture. Randy and Drake cannot even pronounce the word when they first learn about Parris’s intentions to become a psychiatrist, a further indication of her lower-class origins and his lack of sophistication.

Like The Magnificent Ambersons, Kings Row is marked by a dark yet elegiac mood. The values of the old social order are represented by Parris’s grandmother, Madame Von Elm, French by birth, aristocratic by breeding, and one of the community’s pioneers. When grandmother dies, “a whole way of life passes with her, a way of gentleness and honor and dignity that may never come back to the world.”

Yet Kings Row does not prescribe regression into the past; like Magnificent Ambersons, it shows that life must–and does–go on. As much as reality may be painful, coming to terms with the “Truth” is essential for the individual as well as community’s welfare. This set of values (awareness of the “Truth”) will recur in numerous small-town films of the 1950s.

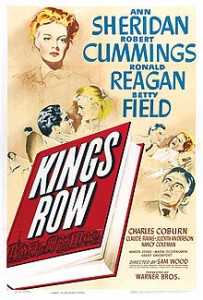

While the lead roles in Kings Row are played by second-rate actors such as Ronald Reagan and Robert Cummings, the supporting ones are cast with Hollywood’s finest character players: Claude Rains, Maria Ouspenskaya, Judith Anderson, Charles Coburn, and Henry Davenport.

Kings Row boasts high production values: Oscar-nominated cinematography by James Wong Howe, and production design by William Cameron Menzies (of Gone with the Wind and Our Town fame). Shot in black and white, the film employs some noir elements. Long shadows are cast in the indoor confrontational scenes, and close-ups are expressions of fear and horror and thus menacing rather than reassuring. The somber cinematography and disquieting editing magnify the feelings of entrapment and claustrophobia. The low-key lighting and oblique camera angles accentuate the film’s distorted vision.

Erich Wolfgang Korngold’s music has dark and oppressive tones too, just as the film’s themes. The critic David Platt (Daily Worker, February 6, 1942) went so far as to praise Kings Row as “the first penetrating psychological study of small-town life, far superior in imagination, and more honest in treatment than Thornton Wilder’s pussy-footing Our Town.

Kings Row’s view of the town as a community is decidedly ambiguous. The town contains good and evil, but no resident can escape its coercive influence, particularly children in their formative years. The themes of paranoia and duplicity–nobody could be trusted, not even your own family–overshadow the neat ending, one that in tune with the times, was meant to restore social order and reassurance. Graduating from medical school, Parris returns to Kings Row; his first patient is Drake, his best friend. At the time, the homoerotic overtones in the relationship between Drake and Parris must have eluded the viewers–and the censors.

True love, overcoming obstacles (Drake and Randy’s marriage), and the sacrifice involved in maintaining friendship, are all celebrated in Kings Row.

If this film were made in the 1950s, it probably would have ended with Randy and Drake leaving town and Parris staying in Vienna, but it the 1940s, there was still strong belief in dominant culture about the moral power of small-town life, and the superiority of collective over individual interests.

Ann Sheridan as Randy Monaghan

Robert Cummings as Parris Mitchell

Ronald Reagan as Drake McHugh

Betty Field as Cassandra Tower

Charles Coburn as Dr. Henry Gordon

Claude Rains as Dr. Alexander Tower

Judith Anderson as Mrs. Harriet Gordon

Nancy Coleman as Louise Gordon

Kaaren Verne as Elise Sandor

Maria Ouspenskaya as Madame von Eln

Harry Davenport as Colonel Skeffington

Ernest Cossart as Pa Monaghan

Ilka Grüning as Anna

Pat Moriarity as Tod Monaghan

Minor Watson as Sam Winters