In the 1950s, producer Ross Hunter and director Douglas Sirk collaborated on a series of melodramas that were largely viewed (and dismissed by most critics) as “weepies,” or “women’s pictures,” neglecting to acknowledge their critique of American society and its mores, their ironic approach to “dubious” texts (such as tear-jerker books and soap operas) and their audacious visual style, which turned them into genuine works of art.

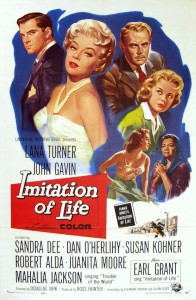

One of the four masterpieces directed in the 1950s, the visually lush, meticulously designed and powerfully acted “Imitation of Life,” was the jewel in Sirk’s crown, ending his Hollywood’s career before he returned to his native Germany. It followed three other popular melodrams: “Blind Ambition,” All That Heaven Allows,” and “Written on the Wind,” all starring Rock Hudson (See my reviews).

One of the four masterpieces directed in the 1950s, the visually lush, meticulously designed and powerfully acted “Imitation of Life,” was the jewel in Sirk’s crown, ending his Hollywood’s career before he returned to his native Germany. It followed three other popular melodrams: “Blind Ambition,” All That Heaven Allows,” and “Written on the Wind,” all starring Rock Hudson (See my reviews).

Made at Universal, Sirk’s version is a remake of John M. Stahl’s 1934 movie, also called “Imitation of Life,” based on Fannie Hurst’s best-selling novel, starring Claudette Colbert and Louise Beavers. (See my review)

The tale centers on two broken families, headed by single women. The two mother-daughter pairs consist of a beautiful, young white widow and struggling actress Lora Meredith (Lana Turner) and her Barbie-doll child Susie (Sandra Dee), and the black and homeless housekeeper Annie Johnson (Juanita Moore) and her light-skinned daughter Sarah Jane (Susan Kohner), who tries to pass for white.

The narrative is divided into two main chapters: The first, largely set in the 1940s, deals with Lora Meredith’s initial hard life, her slow rise to fame and her complicated relationships with men, including her seedy agent Alan Loomis (Robert Alda, father of Allan). Though conscious of the price she pays for her ambition, she continues to alienate the people around her. “Maybe I should see things as they really are and not the way I want them to be,” she says tellingly early on. And indeed, a running motif of the film is the discrepancy between reality and appearances, which explains Sirk’s elaborate use of surface, mirrors, and staircase.

The second, and main, part is set at present and shows a detailed portrait of Lora’s troubled relationships with all the characters around her, the angelic African-American Annie Johnson, the tormented Sara Jane who causes grief and embarrassment, and Steve Archer (played by the stiff and handsome John Gavin) whose love she initially rebuffs. Sandra Dee, just before becoming the most popular teen star in Hollywood, plays Turner’s daughter as a teenager, who falls for her mother’s beau. She’s whining and resentful when she’s told she can’t marry mother’s boyfriend, who himself is uncomfortable with Turner’s skyrocketing career.

The second, and main, part is set at present and shows a detailed portrait of Lora’s troubled relationships with all the characters around her, the angelic African-American Annie Johnson, the tormented Sara Jane who causes grief and embarrassment, and Steve Archer (played by the stiff and handsome John Gavin) whose love she initially rebuffs. Sandra Dee, just before becoming the most popular teen star in Hollywood, plays Turner’s daughter as a teenager, who falls for her mother’s beau. She’s whining and resentful when she’s told she can’t marry mother’s boyfriend, who himself is uncomfortable with Turner’s skyrocketing career.

Meanwhile, Sarah Jane grows into a vapid and tormented woman, who cruelly brings on her mother’s death by dating white boys (including Troy Donahue), beaten by them when they discover her race, and running away from her mother, while performing in shabby nightclubs while denying her past.

The movie ends on a glorious note: A dying Annie Johnson requests the funeral she has always wanted, “four white horses and a band playin,” and her wish is fulfilled with Mahalia Jackson belting out in full volume “Trouble in the World.”

Lana Turner’s shiny blonde hair, elaborate coiffures, and glitzy costumes (she changes outfits in every scene) may call attention to themselves, but they are essential attributes of and complementary to her powerful and sympathetic performance. With this picture, Turner reached the height of her acting career, marked with one Oscar nomination, also for a terrific turn, in the small-town melodrama “Peyton Place,” two years earlier. (Critics who claim that Lana Turner was a “plastic Hollywood star” who could not act, should watch these two pictures).

Lana Turner’s shiny blonde hair, elaborate coiffures, and glitzy costumes (she changes outfits in every scene) may call attention to themselves, but they are essential attributes of and complementary to her powerful and sympathetic performance. With this picture, Turner reached the height of her acting career, marked with one Oscar nomination, also for a terrific turn, in the small-town melodrama “Peyton Place,” two years earlier. (Critics who claim that Lana Turner was a “plastic Hollywood star” who could not act, should watch these two pictures).

“Imitation of Life” and the other Sirk melodramas have inspired the work of such gifted directors as German Rainer Wener Fassbinder (too many melodramas to name here), Spaniard Pedro Almodovar (“High Heels,” and others) American Todd Haynes (“Far From Heaven” in 2002).

Famous lines:

In one of the film’s most emotional moments, Annie says about her suffering daughter: “How do you explain to a child that she was born to be hurt.”

End Note

End Note

I am grateful to the great film critic and professor Andrew Sarris, who showed this film in a course that I took at Columbia in the 1970s, and whose revelatory commentary on Sirk in Film Culture magazine and in his revolutionary book, “The American Cinema” (the Bible of Auteurism) has forever changed the status of this director in film history.

Oscar Alert

Oscar Nominations:

Supporting Actress: Susan Kohner

Supporting Actress: Juanita Moore

Oscar Context

The winner of the 1959 Supporting Actress Oscar was Shelley Winters for George Stevens’ Holocaust drama, “The Diary of Anne Frank.”

Cast:

Lora Meredith (Lana Turner)

Annie Johnson (Juanita Moore)

Steve Ascher (John Gavin)

Susie, age 16 (Sandra Dee)

Sarah Jane, age 18 (Susan Kohner)

David Edwards (Dan O’Herlihy)

Allen Loomis (Robert Alda)

Mahalia Jackson (Herself)

Susie, age 6 (Terry Burham)

Sarah Jane, age 8 (Karen Dicker)

Crew

Produced by Ross Hunter

Directed by Douglas Sirk

Screenplay: Eleanore Griffin and Allan Scott, based on the novel by Fannie Hurst.

Cinematography: Russell Metty.

Editor: Milton Carruth.

Music: Frank Skinner.

Art direction: Alexander Golitzen, Richard H. Riedel.

Costumes: Jean Louis, Bill Thomas

F/X: Clifford Stine.

Running time: 125 Minutes.