Home from the Hill was MGMs latest foray into the then popular Southern family melodrama. Though based on different source materials, The Long Hot Summer, Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, The Sound and the Fury, Written on the Wind all share similar locales and characters: Old plantation houses, randy or cranky patriarchs, neurotic sons, and nymphomaniac daughters.

Grade: A- (****1/2* out of *****)

Their stories disclose nasty skeletons in the families closets, such as adultery, drunkenness, police arrests, and insanity. In most of these melodramas, be they set in New England towns, Texas hamlets, and California suburbs, the stories are about insensitive and boozy fathers, sexually frustrated or repressed wives, and misunderstood or rebellious boys.

Along with Some Came Running, Home from the Hills represents the finest of Minnelli’s lurid melodramas, a flamboyant yet deeply emotional and incisive exploration of family life at its most dysfunctional, a far cry from Father of the Bride. Though in its basic setting and plot, Some Came Running deploys some of the genres basic elements, it was Home from the Hills that assembled all of the genres thematic and visual conventions. One of Minnellis very best; overall, its a more accomplished melodrama than Some Came Running.

William Humphreys “Home from the Hill,” his first novel, was set in East Texas, where he was born. Having adapted Faulkner’s stories into The Long Hot Summer, husband and wife team Irving Ravetch and Harriet Frank Jr. wrote a script that updated the period from the 1930s to the present, and inserted a more reconciliatory conclusion.

As with his 1958 melodrama, Some Came Running, Minnelli thought that the writers have actually improved on the novel. They soon would become Hollywood experts on the South, with future films like Hud, The Reivers, Conrack, Norma Rae, most of which were directed by Martin Ritt and were reasonable successful.

Mitchum plays Captain Wade Hunnicutt, the ferociously macho head of a wealthy Texan family, whos married to an embittered, sexually withdrawn wife (Eleanor Parker) and is the biological father of a Mamma’s boy (George Hamilton) and unacknowledged father of an older, illegitimate son (George Peppard).

The movie is the chronicle of the destructive legacy of one divided family. Wade and his disdainful wife Hannah play out their marital conflicts and power games over their son Theron. In the book, Wade had spawned many offsprings, but in the movie, the scripters combined them into one composite character, Rafe. A resilient figure, Rafe serves as a dramatic contrast to Theron, the legit but pallid Hunnicutt heir.

A modern Texas yarn that was a precursor to TVs soap opera Dallas, with Mitchum as the proto-Jock, Eleanor Parker the suffering proto-Ellie, George Hamilton as proto-Bobby and George Peppard as a composite proto-JR/proto-Ray. Dealing with pregnancy, illegitimacy, and other scandals, it’s a melodrama, where men are men and the women have to put up with them.

The acting, particularly by Mitchum, is strong. As the lecherous patriarch, he conveyed the character’s masculine virtues, and a vague awareness of the heavy toll he had on his life and his familys. Captain Hunnicutt tells his son Theron: “You’re my next of kin–legal, legitimate, born in marriage, with my name and everything that goes with it. And that’s the way of the world. There are the ins and the outs, the haves and the have-nots. You’re lucky, you’ve got yours.”

Rafe, the bastard as a victim of society, was a staple in such melodramas. He is Therons masculine counterpoint, Wade’s illegitimate son who had inherited his father’s characteristics and is loved by him. Home from the Hills is as much about Rafe’s search for legitimate identity, as it is about Theron’s search for masculine identity. Theron’s failed effort to find a place within the family hinges on his discovery of Rafe’s bastardy. The two searches are inversely related: Theron takes Rafe’s place as social outcast, and vice versa.

Theron is legally his son, but Hunnicutt doesn’t feel connected to him because he’s a mama’s boy. But, in the end, Theorn is the active agent of this re-constitution of the divided family, purging the corruption and seeing that justice prevails, namely, that Rafe gains legitimate recognition from his father.

Wades wife, Hannah, has refused to sleep with Wade ever since she learned of Rafes existence. She has agreed to stay with Wade on one condition, that Theron be exclusively her son, thus turning him into an overly sensitive Mamas boy. At the center of the melodrama is the survival of the family by transmitting the right values and proper inheritance, and assigning the suitable identities to all the family members, legitimate and illegitimate, within the symbolic and social order of society.

In the film’s opening scene, Wade, the hunter implied in the title, returns from the hill. The hunt is the film’s metaphor for masculinity, and it divides the male characters into masculine versus non-masculine, the hunters versus the hunted, the strong versus the weak, the protectors versus the protected. The hunter survives and rules by gaining strength and endurance, cunning and violence, but he must always return to his family, if he is to find home, love, and tenderness.

The men’s world, and the peripheral part the women play in it, is established right away with the hunt. Wade is seen with his dogs, his men crouched in a swamp, aiming at ducks flying overhead. Just seconds before we hear the shot that hits Wade in the shoulder, Rafe notes that the attention of one dog has been distracted, and flings himself forward to knock Wade out of the line of fire. Rafe saves his fathers life, when the cuckolded husband of one of the many women Wade had slept with, tries to kill him. Even wounded, Wade looks powerful. He sits on the table in the foreground, erect, bare-chested, wearing his Texan hat and drinking whiskey.

Its left to the doctor to convey the films rather pessimistic message: “Wade, I’m going to tell you how we small-town Texans get our name for violence. It’s grown men like you still playin’ guns and cars. You never will grow up will you It’s gettin’ to where a man ain’t a man around here anymore unless he uses a car, goes down a road at a hundred miles an hour, owns six or seven fancy shotguns, knows six or seven fancy ladies!

Minnelli frames the characters so that each event” illustrates a facet of their masculinity code. Masculinity is articulated in Mitchum’s appearance, which is contrasted with his doctors, whos short, plump, balding, and bespectacled. Objecting to the hunt, the doctor sees it as adolescent ritual of masculinity, based on power, conquest, and physical strength.

Nonetheless, Hunnicutt is forced to pay for his life Hes fatally shot by a man who believes his daughter’s child, was fathered by Wade. The “right” to cross any man’s fence when he is hunting signals Wade’s original corruption. Wade breaks the rules, which he believes are only for the weak members of society, effeminate men like the doctor, women, and children.

Last Scene: Spoiler Alert

Set in the cemetery, the last scene depicts a reunion between Hannah and Rafe, Hunnicutt’s illegitimate son, who is now recognized a legit member of the family, with Rafe offering, “let’s go home.”

Critical and Commercial Status

Robert Mitchum received the Best Actor kudo from the National Board of Review (NBR).

In the same year, Mitchum appeared in another domestic tale, Zinnemann’s The Sundowners, opposite Deborah Kerr, an inferior film that nonetheless went on to Oscar glory with an undeserved Best Picture Oscar nomination.

Home from the Hill was popular at the box0office.

Cast

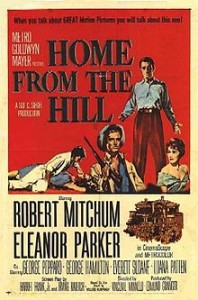

Robert Mitchum as Capt. Wade Hunnicutt

Eleanor Parker as Hannah Hunnicutt

George Peppard as Raphael ‘Rafe’ Copley

George Hamilton as Theron Hunnicutt

Everett Sloane as Albert Halstead

Luana Patten as Elizabeth ‘Libby’ Halstead

Anne Seymour as Sarah Halstead

Constance Ford as Opal Bixby

Ken Renard as Chauncey (Hunnicutt butler)

Ray Teal as Dr. Reuben Carson

Credits:

Directed by Vincente Minnelli

Screenplay by Harriet Frank Jr. and Irving Ravetch, ased on Home from the Hill by William Humphrey

Produced by Edmund Grainger

Cinematography Milton R. Krasner

Edited by Harold F. Kress

Music by Bronislau Kaper

Distributed by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer

Release date: March 3, 1960 (US)

Running time 150 minutes

Budget $2,354,000

Box office $5,075,000