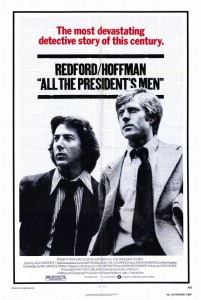

Artistically and commercially, Alan Pakula’s All the President’s Men, made in 1976, is one of the most successful and poignant American political movies.

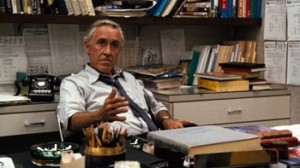

This top winner by the New York Film Critics Circle was also nominated for the Best Picture Oscar, and won four Oscar awards: Adapted Screenplay for William Goldman, Supporting Actor for Jason Robards (as Washington Post editor Ben Bradlee), Art Direction, and Sound.

It lost the coveted award to Sylvester Stallone’s Rocky, a rather conventional, populist film that was popular with Academy voters and the public at large.

Structured as a gripping thriller, the film chronicles the real-life “adventures” of journalists Bob Woodward (Robert Redford) and Carl Bernstein (Dustin Hoffman) in uncovering the story behind the 1972 attempted burglary at the Democratic Party headquarters in Washington D.C.’s Watergate complex.

One of the film’s merits is that it captures vividly the tedious process of journalism (the long wait for leads, the failed attempts to get information from key witnesses, the soul-searching, the dead ends) as well as the excitement of the end result, when the process does lead to a triumph.

Produced by Redford’s company (Wildwood Enterprises), the film has also had great effect on actual changes of the American political process. Released in 1976, during the Carter-Ford presidential campaign, All the President’s Men may have helped to turn the tide in Carter’s favor.

Companion piece: Read our review of All the King’s Men

emanuellevy.com/review/oscar-history-best-picture-all-the-kings-men-1949/

Viewing the film upon its initial release in April 1976, the Boston Mayor Kevin White remarked, “That film is going to have an effect on the election, it is powerful.” But can we really attribute Ford’s defeat primarily to All the President’s Men Was the film actually that powerful Ronald Reagan thought so. Reagan, who in 1976 was the governor of California, recognized the film’s power, confessing that All the President’s Men had indeed cost the Republicans the presidency.

“All the President’s Men” brought to the surface all the implications of Watergate that the Republicans had tried hard to bury in the months leading up to the campaign. The film taught politicians a lesson they will not soon forget–a lesson about how far Americans will go in believing movies. When the release of the John Glenn homage The Right Stuff coincided with Democrat Glenn’s 1984 presidential bid, 8 years after All the President’s Men, the Republican Party became paranoid. We can attribute this reaction to the Republicans’ unpleasant memories of how All the President’s men hurt them in 1976, having a massive effect on American votes and thus on the course of the entire nation. Screenwriter William Goldman went so far as to say that “All the President’s Men” “just might have changed the entire course of American history.”

“All the President’s Men” brought to the surface all the implications of Watergate that the Republicans had tried hard to bury in the months leading up to the campaign. The film taught politicians a lesson they will not soon forget–a lesson about how far Americans will go in believing movies. When the release of the John Glenn homage The Right Stuff coincided with Democrat Glenn’s 1984 presidential bid, 8 years after All the President’s Men, the Republican Party became paranoid. We can attribute this reaction to the Republicans’ unpleasant memories of how All the President’s men hurt them in 1976, having a massive effect on American votes and thus on the course of the entire nation. Screenwriter William Goldman went so far as to say that “All the President’s Men” “just might have changed the entire course of American history.”

“All the President’s Men” has become an historical document, an official version of the Watergate scandal. The film was made quickly after Watergate had ended, during the lingering aftermath of Nixon’s resignation. Pre-production, on the part of Robert Redford, actually began during the Watergate trials. All the President’s Men hit before the issue had the chance to become anything like dry textbook history. Americans were still trying to figure out all the ramifications of what had happened. New information about the extent of the Nixon administration’s blunders, as well, was still surfacing day-by-day back in 1976.

The film was released on April 7 1976, and did good business from the start. All the President’s Men enjoyed a long run, which coincided with the election campaign, and thus secured Carter as president. Included in the film is footage of Representative Gerald Ford nominating Nixon at the 1972 Republican National Convention, which clearly associated Ford with Nixon as a Nixon dupe in 1976. Gerald Ford was an unwilling cameo star in a film that insured his failure. In a way, All the President’s Men was a full-length Hollywood commercial against Ford’s campaign. Subsequently, the very first film screened in the Carter Whitehouse was none other than All the President’s Men.

The film was released on April 7 1976, and did good business from the start. All the President’s Men enjoyed a long run, which coincided with the election campaign, and thus secured Carter as president. Included in the film is footage of Representative Gerald Ford nominating Nixon at the 1972 Republican National Convention, which clearly associated Ford with Nixon as a Nixon dupe in 1976. Gerald Ford was an unwilling cameo star in a film that insured his failure. In a way, All the President’s Men was a full-length Hollywood commercial against Ford’s campaign. Subsequently, the very first film screened in the Carter Whitehouse was none other than All the President’s Men.

How accurate was All the President’s Men in depicting the Watergate scandal How sound was its political statement What are the film’s politics, besides being anti-Republican The film is perhaps more of a liberal political gesture than a liberal political statement. If All the President’s Men is an idealized Hollywood version of Watergate, then the country’s political climate may have shifted to the left largely due to the delusory effect of presenting Watergate in simplistic black and white terms. This would constitute sweeping political change based on a sort of false pretense, rather than on heartfelt, intelligent and progressive political change.

The film’s reporters are certainly not depicted as acting out of political smartness, but out of the desire to work hard and win, much like the Hardy Boys. The political implications that are implicit in the Watergate story are subjugated to, and translated into, a detective narrative, thus losing their original bite. While All the President’s Men may have won Carter the presidency, the film shies away from real politics, in this way allowing the lessons of Watergate to be forgotten by the time of the 1980 presidential election.

The film’s reporters are certainly not depicted as acting out of political smartness, but out of the desire to work hard and win, much like the Hardy Boys. The political implications that are implicit in the Watergate story are subjugated to, and translated into, a detective narrative, thus losing their original bite. While All the President’s Men may have won Carter the presidency, the film shies away from real politics, in this way allowing the lessons of Watergate to be forgotten by the time of the 1980 presidential election.

The film’s criticisms are centered on Nixon as a bad guy, along with his bad guy cronies. At the same time, the film fails to find fault with the system that allowed Nixon to commit the crimes that he committed. Actually, All the President’s glorifies the system it pretends to question, suggesting that the system still works, in that it shows us a couple of youthful descendants of Horatio Alger toppling a corrupt government. The film reveals the evil in the system, but then celebrates how the system can still rectify itself.

This is what led the New York Times’ Vincent Canby to call All the President’s Men, “An accurate picture of America at its best.” Could it be that this film is actually a sort of endpoint for 1960s politics, rather than a climax to 1960s liberalism While the film seems to suggest the triumph of 1960s liberalism over a decrepit establishment, All the President’s Men lends power to the standard system. Woodward and Bernstein are firmly planted in the system and with the system.

This is what led the New York Times’ Vincent Canby to call All the President’s Men, “An accurate picture of America at its best.” Could it be that this film is actually a sort of endpoint for 1960s politics, rather than a climax to 1960s liberalism While the film seems to suggest the triumph of 1960s liberalism over a decrepit establishment, All the President’s Men lends power to the standard system. Woodward and Bernstein are firmly planted in the system and with the system.

The driving force behind the film was actor Robert Redford (who plays Woodward), a noted champion of liberal causes in the 1970s, who had a personal dislike for Nixon. Redford was, at the time, the number one movie star in the world. His superstar appeal makes the anti-Nixon Watergate sentiments more palatable. Redford’s presence gives the film’s liberal posing an acceptability and attractiveness. It was Redford that first encouraged the Washington Post reporters Woodward and Bernstein in the direction of writing a narrative account of their experience (which became the book version of All he President’s). When Redford was 13, he had a fateful meeting with Nixon, which formed his impression of him as a foe. Redford won a tennis tournament in Van Nuys, California, his hometown, with Nixon in attendance. Then-Senator Nixon awarded the young Robert Redford the trophy and Redford claims that he thought to himself of Nixon, “What a non-person! This fake human!”

All the President’s did more than just change our perceptions of politicians, as fake or otherwise: the film had an even more profound influence on our image of journalists than on our image of politicians. The film opens with huge typewriter keys, larger than life, pounding away. It’s a visual metaphor for the alluring power of the press. The thrill of reporters fighting corruption (similar to the thrill of cowboys fighting Indians) subsequently imbues All the President’s Men. The film showed journalism, as people wanted it to be: epochal and exciting. All the President’s Men is the Mr. Smith Goes to Washington of journalism. Every attack on the Washington Post in the film was an attack on the foundations of freedom. As a result, about 50,000 students enrolled in Journalism schools after the Woodward and Bernstein story entered popular mythology.

The film made “The Washington Post” a legend, and the reporters Woodward and Bernstein and editor Bradlee into celebrities. Ben Bradlee stated in retrospect that “the irony of Watergate is that Richard Nixon made us all famous – the people he most despised. He made us mini-household words, and in the case of Woodward and Bernstein, real folk heroes.”

All the President’s Men popularized, and even invented the notion of investigative reporting, as we know it today–or rather, as we want it to be.

That said, it’s hard not to notice how cheerful and ultimately optimistic the movie was, emphasizing the heroics of crusading journalism at the expense of concealing the darker, more compromising aspects of American politics. In a typically Hollywood manner, All the President’s Men turned its theme of justice into mainstream entertainment, showing how “dirty” facts turned into mythic legend within a very short period of time.