The Courtship of Eddie’s Father, Vincente Minnelli’s first film under the new Venice pact (created by him and his then wife Denise), was a modestly scaled and budgeted domestic comedy.

The feature was based on Mark Toby’s autobiographical novel, about the readjustment problems of a recently widowed radio executive and his relationship with his precocious son.

Assembled by Toby and his friend Dorothy Wilson, the stories were later polished by another writer.

The three women in the widower’s new life, who come across as types, actually represent different (if idealized) facets of Wilson, who owned the copyrights to the text.

Hoping to grab the TV audience, Metro favored this kind of cute family portrait, but, from the start, it didn’t excite Minnelli. He not only found the story to be disappointing, but also feared that his efforts would result in “a very little picture, as he told his wife.

Moreover, it was produced by Joe Pasternak, a less demanding or skillful supervisor than Arthur Freed or Pandro Berman, who has specialized in broad, corny family fare.

The film was written by John Gay, who was an odd choice for the project since he was the one who had co-written Minnelli’s disastrous epic, Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse.

Introduced to the Cobett household just days after the death of Eddie’s mom, the film observes the gradual adjustment endured by the two survivors, father and son, who necessarily but unintentionally evolve to become co-dependent on each other.

To everyone’s surprise, even an innocuous film like The Courtship of Eddie’s Father faced censorship problems. There were objections to Eddie’s vague observations about female anatomy (chest and waist size), which had to be modified in order to gain the Codes seal of approval.

In one specific scene, Eddie describes to his dad the qualities of skinny-eyed, big-busted women. In another, he asks their friendly neighbor how babies are made, just as his father walks in.

And in a later scene, Eddie shows mature curiosity about women’s measurements, prompting his father to say, “I don’t carry around a tape measure.”

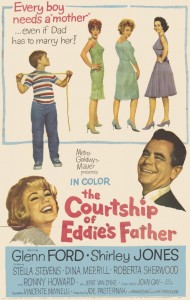

Glenn Ford, then under contract at MGM and at the height of his popularity, was cast in the lead, this time with Minnelli’s approval. Rendering a grounded and credible performance, Ford shows strong rapport and ease with Ron Howard and each of the three women.

The three women were played by Shirley Jones, as the wholesome widow, living across the hall; Stella Stevens, as a sweet but dense Dollye, in a role similar to Shirley MacLaine’s Ginney in Minnelli’s superior melodrama, Some Came Running, and Dina Merrill.

Looking for a young boy to play the virtuoso kid, Minnelli cast the smart red-haired Ronnie Howard. Howard had already scored big in the 1958 musical The Music Man and was a favorite child actor as Opie on TVs The Andy Griffith Show. (Howard later became a famous Hollywood director, winning an Oscar for the 2001 drama, A Beautiful Mind).

Shooting began on August 1, 1962 and ended on time in early October. Minnelli was pressured to keep the costs down, after the huge budgets spent on his last couple of pictures., none of which did well at the box-office.

As a result, the New York locations were recreated on the studio backlot, and a wedding sequence was scaled down from a church ceremony to a reception in an apartment that was also used elsewhere in the picture.

The studio allocated $1,800,000, the lowest budget for a Minnelli picture since 1950, of which his directorial fee, $195,000, was the biggest item, amounting to ten percent.

When The Courtship of Eddie’s Father opened, in June 1963, the critics found it sentimental and only intermittently engaging. The public’s response was mild too, and MGM was forced to declare a deficit.

The film enjoyed a future life on the small screen as a popular family sitcom, often shown on Father’s Day, for which it was most suitable.

For Minnelli’s part, Courtship of Eddie’s Father provided a kind of occupational therapy, after the bickering and scandals on the set of Four Horsemen and Two Weeks in Another Town, both of which big commercial flops.

But the film was modest–and TV-like–to a fault. The cut-rate cast and studio look confirmed the film status, as a minor work, not more than a footnote in Minnelli’s career. Courtship does not even qualify as a stylish exercise, though Minnelli shows his favorite palette of colors, red and yellow, in almost every scene. Men’s vests, Howard’s jackets, housekeeper’s apron, and various furniture pieces are all in red.

To conform to the new production circumstances and movie market conditions, Minnelli lowered his standards and, as a result, his customary signature is absent from the picture.

Moreover, the Panavision panoramas clash with the films intimate theme, further exposing the undernourished yarn. The movie’s sound was even tackier than its visuals, overseen by Milton Krasner. Like many studio films, The Courtship of Eddie Fisher lagged behind the tastes and spirits of the times, it was too artificial to ring true as a family melodrama, too straight to qualify as comedic fantasy.

Nonetheless, Courtship of Eddie’s Father contains one vital element that was missing from Minnelli’s recent comedies, an emotional center. Like Frank Capra’s 1959 Hole in the Head, a better film with Frank Sinatra in the lead, Minnelli offers a melancholy portrait of a widowed father, then a relatively new screen hero in Hollywood movies.

As he showed in Meet Me in St. Louis, Minnelli views childhood not as a cheerful phase but as a painful period with dark and brooding tone. Eddie exhibits a similar kind of morbid sensibility that Margaret O’Brien’s Tootie had shown in Meet Me in St. Louis. Both Tootie and Eddie are forced to come to terms with such mature issues as death or sex, and both have to endure growing pains with intense sorrow.

Though minor and forgettable in the overall scheme of Minnelli’s (and Glenn Ford’s) careers, The Courtship of Eddie’s Father is perfectly watchable, serving as a capsule to American family mores of the early 1960s, soon to be changed radically due to the Vietnam War and the political assassinations of the Kennedys and Martin Luther King.

Cast:

Tom Corbett (Glenn Ford)

Eddie Corbett (Ron Howard)

Elizabeth Marten (Shirley Jones)

Rita Behrens (Dina Merrill)

Dollye Daly (Stella Stevens)

Mrs. Livingston (Roberta Sherwood)

Norman Jones (Jerry Van Dyke)

Jazz Combo (John La Salle)

Credits

Produced by Joseph Pasternak

Assistant Director: William McGarry.

Screenplay: John Gay, from the novel by Mark Toby

Cinematography: Milton Krasner

Art Direction: George W. Davis, Urie McCleary

Set Decoration: Henry Grace, Keogh Gleason

Music: George Stoll

Song, “The Rose and the Butterfly,” by Victor Young and Stella Unger

Editing: Adrienne Fazan

Costumes: Helen Rose

Print process: Metrocolor

Recording Direction: Franklin Milton

Hair Stylist: Sidney Guilaroff

Makeup: William Tuttle

Running Time: 117 Minutes