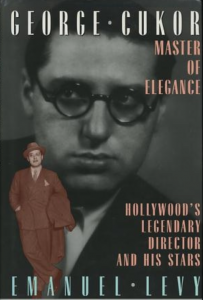

The Chapman Report, with Richard Zanuck as producer and George Cukor as director, was initially set to be a Twentieth Century Fox production. However, as Zanuck told me: “there was a lot of turmoil at the studio, it was the beginning of the ‘Cleopatra’ debacle. They were very disorganized, and they decided that this project was too risky and had no foreign potential. We were pretty far advanced in the production, though we hadn’t started shooting. It took one telephone call from my father (Daryl F. Zanuck, head of Fox) to Jack Warner, he took it right away.”

Grade: C+ (** out of *****)

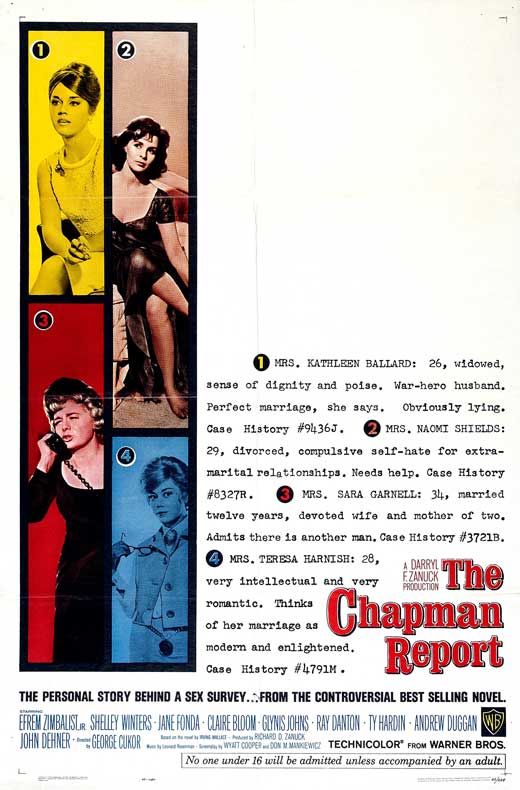

Based on Irving Wallace’s scandalous novel, “The Chapman Report” has an episodic structure, and sociological texture, cross-cutting among the stories of four “typical” American women. They are meant to be representative of the female gender, with the film focusing on their erotic desires (and repressions), actual sex lives, and emotional frustrations with men. (All the women are straight, of course).

A team of sexologists, not unlike the Kinsey researchers, arrive in the suburb of Brentwood in order to unearth some “startling behavioral truth” about the “respectable” married set.

By today’s standards, the film is mild, but there was a great outcry about how shocking and indecent the contents of the book was upon its initial publication.

The Chapman Report was heralded as the “sexiest” movie ever made in America, but despite all the hype that it received, the promised salaciousness and sleazy scenes were never there.

Censorship

The Production Code office expressed its strong concern with “the quantity of the sex episodes as well as the treatment of each incident.” Any one of the four sex episodes–a nymphomaniac, an adulterous wife, a frigid woman, a dissatisfied wife–would be sufficient material for one controversial movie, but piled into one picture, and discussed in clinical language, was unacceptable by standards of the time.

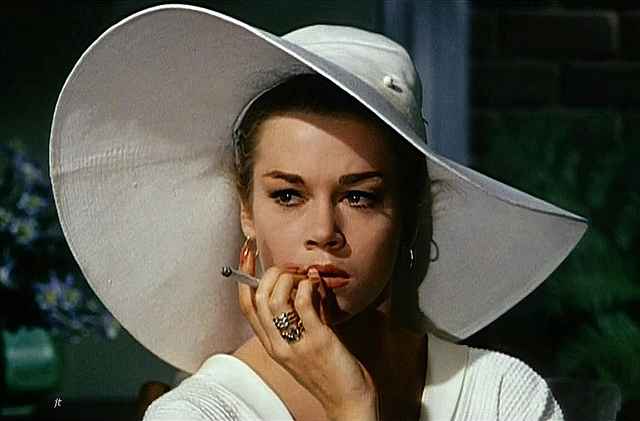

As trashy as the material was, Cukor treats it with discretion and subtlety. The melodrama is considerably elevated by Cukor’s casting and tasteful direction. He cast three first-rate actresses: Claire Bloom, Shelley Winters, and Glynis Johns. The fourth actress, Jane Fonda, who was only 24, showed potential but was not established yet as a major talent.

But if the casting is near perfect, the script is not. As many as seven writers worked on the script, but in the end, Wyatt Cooper and Don Mankiewicz were credited for the script, and Grant Stuart and Gene Allen for adaptation. In actuality, Allen wrote the final scenario almost singlehandedly.

If Chapman Report is vaguely interesting today, it is largely for its acting, especially Claire Bloom’s performance. Having played many parts in the theater, Bloom’s skills are dazzling. According to Claire Bloom, “Cukor was very interested in issues of female sensitivity. He lived vicariously through certain of the tenacious feelings that I played. He experienced the material in a different way, because he was homosexual. Like many highly tuned artists, he knew what it was to be a man and a woman.”

The costumes are designed by a very good designer, Oscar-winner Orry Kelly. Every woman wears one dominant color all the way through. For example, Bloom’s color is brown and Winters’ black. This gimmick makes every woman stand out.

The Production Code officials fulfilled their “promise” to “scrutinize the finished film with minute care.” They reminded Zanuck and Cukor that one of their agreements was that the word sex would be eliminated wherever possible, to avoid giving the impression that the story was concentrating heavily on sex. But to their dismay, the word sex was used excessively: as much as five times on two pages. The dialogue seemed too specific–the word intercourse was used in too outspoken a manner.

Cukor was volatile about censorship issues, particularly when Warners decided to change the ending. Cukor liked the idea that his film actually proved, rather devastatingly, that the American woman was a “kinky” item. But to avoid an “X” rating, Warner asked for a new ending. In the new version, Andy Dugham and Zimbalist are going over I.B.M. cards, and Dugham says this horrible line: “Well, I think, by and large, the American woman’s pretty normal, wouldn’t you say” And Zimbalist’s answer was, “Yes, completely normal.”

Warners brought in another director to reshoot the ending, but Cukor came back from vacation in Hawaii so that the film wouldn’t be taken away from him. At the end, a lot of stock film ended up on the cutting room floor.

“What was really first class in the film,” Cukor later said, “were these long-sustained interviews with the women who confide their sexual problems to the psychiatrist.

The scenes were extremely well played. Jane Fonda had an emotional scene that was particularly good, but it was cut, cut, cut!”

Comparisons with other film versions of similarly trashy books by Harold Robbins and Jacqueline Susan were in Cukor’s favor, because of his considerable tact and taste.

Hit by Cukor

While filming her first scene in the Chapman Report, Cukor kicked her in the shin. Though a “subtle kick,” it was described as an “unprovoked attack” and by Johns as “so unexpected that I did a terrible sort of double take.” On the set, tensions were high, though she and Cukor later laughed about it and he noted she was “wonderful in the picture.