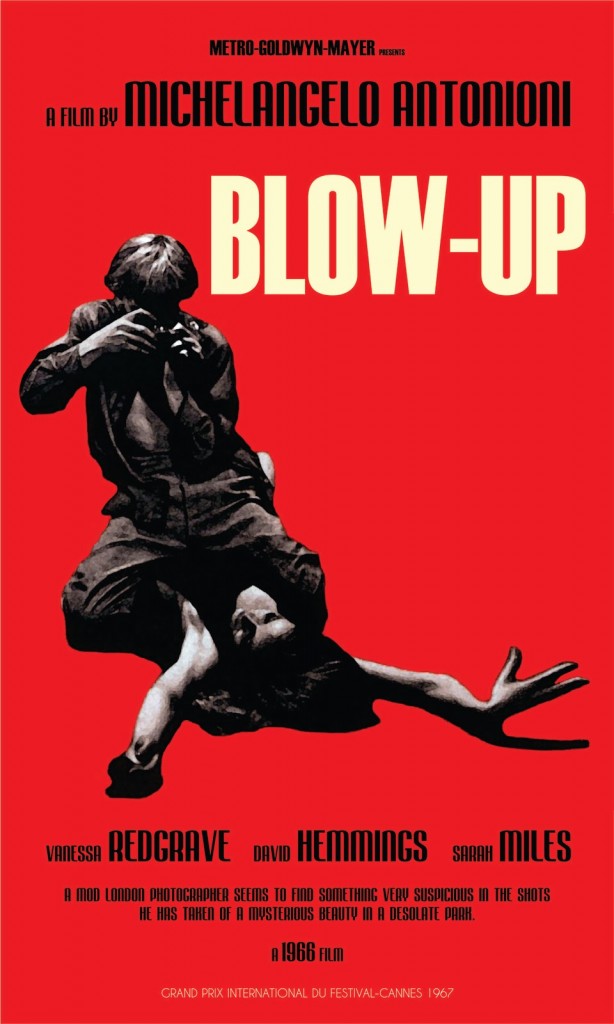

Directed by modernist Italian maestro Michelangello Antonioni in his first English-speaking, “Blow Up” is a seminal movie of the 1960s, at once an influential art film and a pop culture phenomenon, capturing swinging London like no other film before or since.

A biggest surprise box-office hit, “Blow Up,” which had earlier won the Palme d’Or at the 1960 Cannes Film Festival, is still a puzzlingly mysterious, visually stunning, largely unresolved picture, full of intentional and unintentional ambiguities, which may explain why we keep revisiting it.

Inspired by the short story “Las Babas del Diablo” (“The Droolings of the Devil”) by Argentinean writer Julio Cortázar, the film probes into the nature filmmaking, the dialectical relationship between illusion and reality, and the politics of involvement by artists whose professional ethos require moral detachment.

The screenplay was penned by Antonioni and his frequent collaborator, Tonino Guerra, with the English dialogue being written by British playwright Edward Bond. The film was produced by Carlo Ponti, who had contracted Antonioni to make three English language films for MGM (the others were “Zabriskie Point” and “The Passenger”).

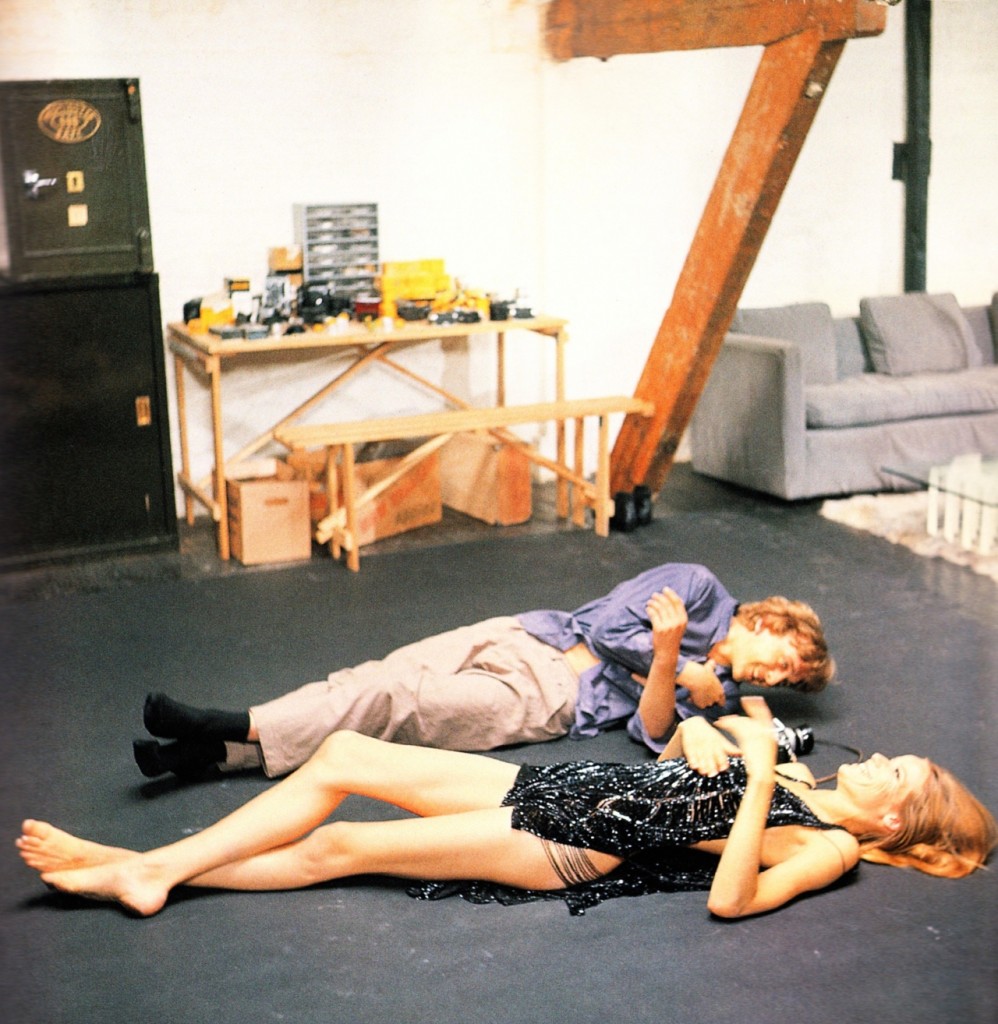

Thomas (David Hemmings), the elusive protagonist, is a young, handsome photographer immersed in a lifestyle of drugs, parties, and orgies with models. Wandering the park one day, Thomas observes from a distance two lovers embracing. The woman, Jane (Vanessa Redgrave), noticing his act, runs after him and asks for the negative back. He refuses. After snapping photos of the couple, he develops them at his studio. The photos disclose a murder mystery: a man with a gun pointed at the back of Jane’s partner.

Later that evening, when Thomas returns to the park, this time without a camera, he finds a man’s corpse on the grass under a tree. At a cool party on the Thames River near central London, Thomas finds the French model and his publishing agent (Peter Bowles). He hopes to bring the latter to the park as a witness, but he can’t articulate what he had seen. By the time he gets back to the park alone, at dawn, the body is gone.

Thomas watches with bewildered amusement some university students playing and watching a mimed tennis match, is drawn into it, picks up their unseen, make-believe ball and throws it back to the two players. While he watches the mimed match, the sound of a ball being played back and forth is soon heard. In the film’s last, impressive shot, Thomas stands alone on the grass before vanishing without a trace.

Thomas Character

The character is loosely based on David Bailey, the genius photographer associated with Twiggy and Jean Shrimpton. His cavorting with the model Veruscka was one of the hottest erotic scenes in film up to that point).

Boyishly handsome, Hemmings became an iconic star as a result of one memorable performance; no movie he has made afterwards generated so much attention.

Other Characters:

Thomas visits his friends who live close by, a young married couple: a painter of abstract art (John Castle) and his sexy wife, Patricia (Sarah Miles).

In a key scene, which might serve as a metaphor for the entire film, the artist says about his paintings: “They don’t mean anything when I do them, just a mess, but afterward, I find something to hang onto, and it sort of adds up, like a clue in a detective story.”

There’s flirtatious relationship between Thomas and Patricia. She caresses his hair in sort of erotic way, and he asks her not to stop because it feels good.

In other scene, when he enters their house, the couple is in bed making love. He stares at them for a while, and Patricia reciprocates with a longing look at him; her husband is unaware of it.

Antonioni’s Contribution

In all of his films, Antonioni made a significant contribution to film art, helping shaped expectations of what narrative is–or could be, and experimenting with visual style that favors extremely long takes, deliberate pacing, and elaborate mise-en-scene over montage.

With the exception of the music—Herbie Hancock’s jazzy score–the movie holds up extremely well. The neo-surreal images are crisp and captivating. Moreover, half a century later, the film’s main theme, individual responsibility, is still relevant. As a cautionary morality tale, Blow-Up shows the ease with which it’s possible to avoid responsibility in a world where there is no clear moral code and no clear line between reality and illusion. In the ambiguous ending, Thomas avoids commitment, altogether renouncing the significance (and even existence) of physical reality.

“Blow-Up” was Antonioni’s foray into more commercial international cinema, after making the highly acclaimed trilogy: “L’Avventura” (1960), “La Notte” (1961) and “The Eclipse” (1962), all starring Monica Vitti, which played in film festivals and were limited to the art house circuit.

It’s the director’s second film in color, after “Red Desert,” in 1964. “Blow-Up” (1966), “Zabriskie’s Point” (1969), and “The Passenger” (1975) were all made in English, in an effort to appeal to a larger, international audience.

Vanessa Redgrave

The year of 1966 was a turning pint in the career of Vanessa Redgrave (daughter of Michael Redgrave), having made the sensational “Blow-Up” as well as the controversial black-and-white indie, “Morgan,” for which she received her first Best Actress Oscar nomination; she also had a cameo in Fred Zinnemann’s “A Man for All Season.”

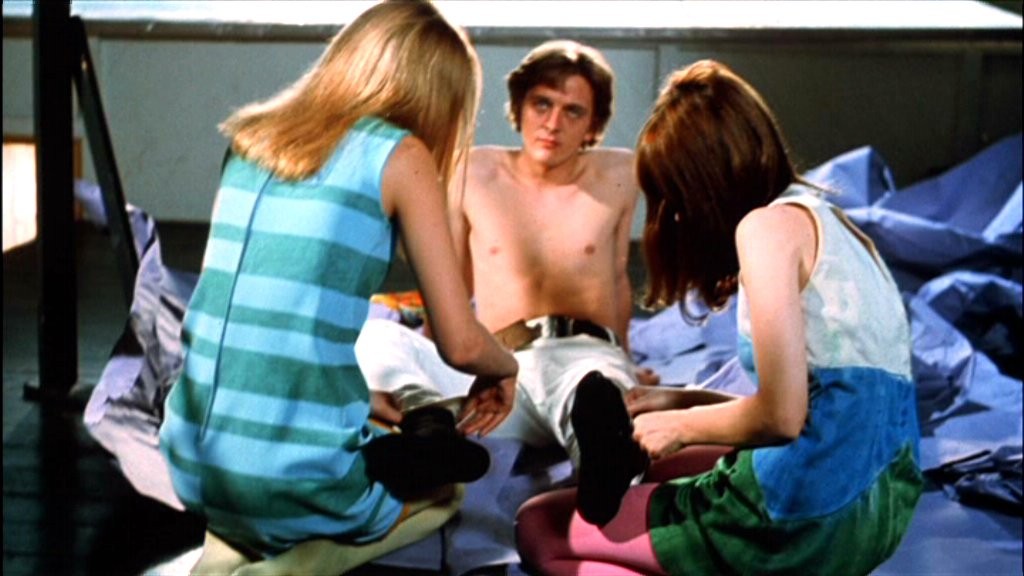

Jane Birkin made her screen debut as one of the teenage girls with whom Thomas has an orgy.

“Blow-up” became a cause celebre due to its sexual content, specifically full frontal female nudity (Redgrave), and an orgy scene, in which Thomas and the two aspiring models roll up, and the women undress him.

When MGM, which distributed the film in the U.S., didn’t get the Seal of Approval from the MPAA Production Code in America, it released the picture through Premier Productions. The film is a seminal turning point in the history of the Production Code, which began to collapse in the mid-1960s (“Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? Was also released in 1966) and was brought to demise in 1968.

Cast

Thomas (David Hemmings)

Jane (Vanessa Redgrave)

Patricia (Sarah Miles)

Bill (John Castle)

Teenager one, aka the Blond (Jane Birkin)

Teenager two, aka the Brunette (Gillian Hills)

Ron (Peter Bowles)

Veruschka von Lehndorff (model) as herself

Shopkeeper (Henry Hutchinson)

Antique shop owner (Susan Broderick)

Fashion editor (Mary Khal)

Julian Chagrin as Mime

Claude Chagrin as Mime

Jane’s lover in the park (Ronan O’Casey)

Reg Wilkins as Thomas’s Assistant (Reg Wilkins)

Thomas’s receptionist (Tsai Chin)

Model (Jill Kennington)

Model (Peggy Moffitt)

Oscar Alert

Oscar Nominations: 2

Director: Michelangelo Antonioni

Story and Screenplay (Original): Antonioni, Tonino Guerra, Edward Bond

Oscar Awards: None

Oscar Context:

In 1966, the winner of the Best Director was Fred Zinneman for “A Man for All Seasons,” which swept the major awards.

The Original Screenplay Oscar inexplicably went to Claude Lelouch and Pierre Uytterhoeven for the French movie, “A Man and a Woman,” which relies more on music and visuals than words.

Guerra was also Oscar nominated (with others) for his scripts for Mario Monicelli’s “Casanova 70” (1966) and Fellini’s “Amarcord,” in 1975.