Orson Welles’ troubled feature, The Other Side of the Wind, which was in production for 15 years, and then went into a state of limbo for decades, was finally publicly unveiled, courtesy of Netflix, as a special presentation of the 2018 Venice Film Fest.

In a festival that’s extremely strong this year in terms of high-quality art films and high caliber Hollywood A-talent (A Star Is Born, starring Bradley Cooper and Lady Gaga, world premiered to great acclaim last night), Welles’ last (unfinished) feature still stands out as a cause for celebration for many cineastes and cinephiles who have been eagerly awaiting to see it.

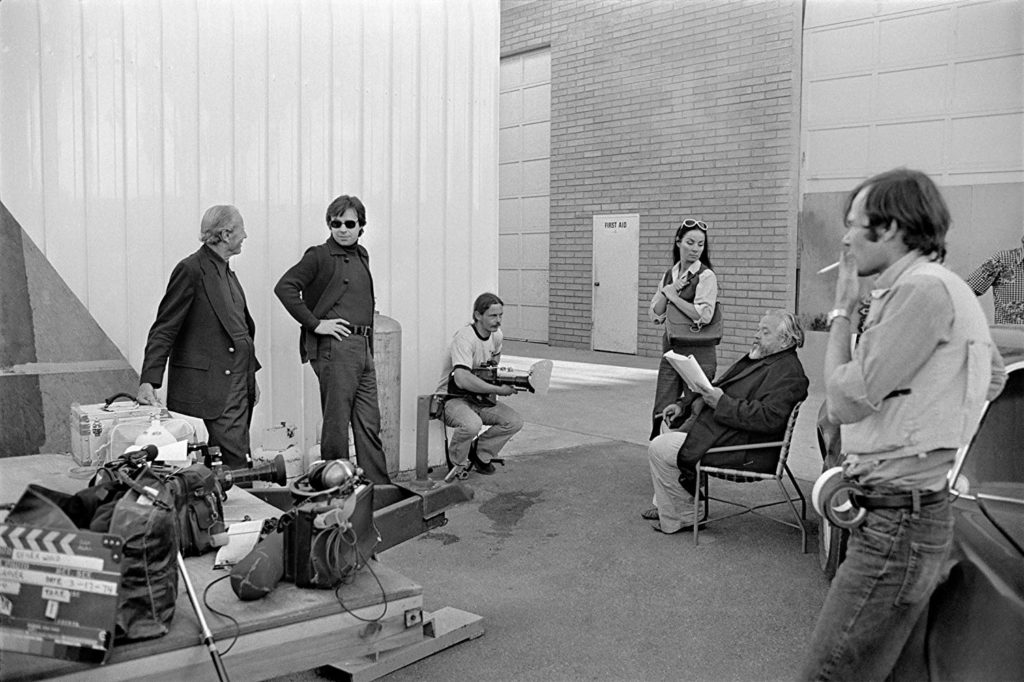

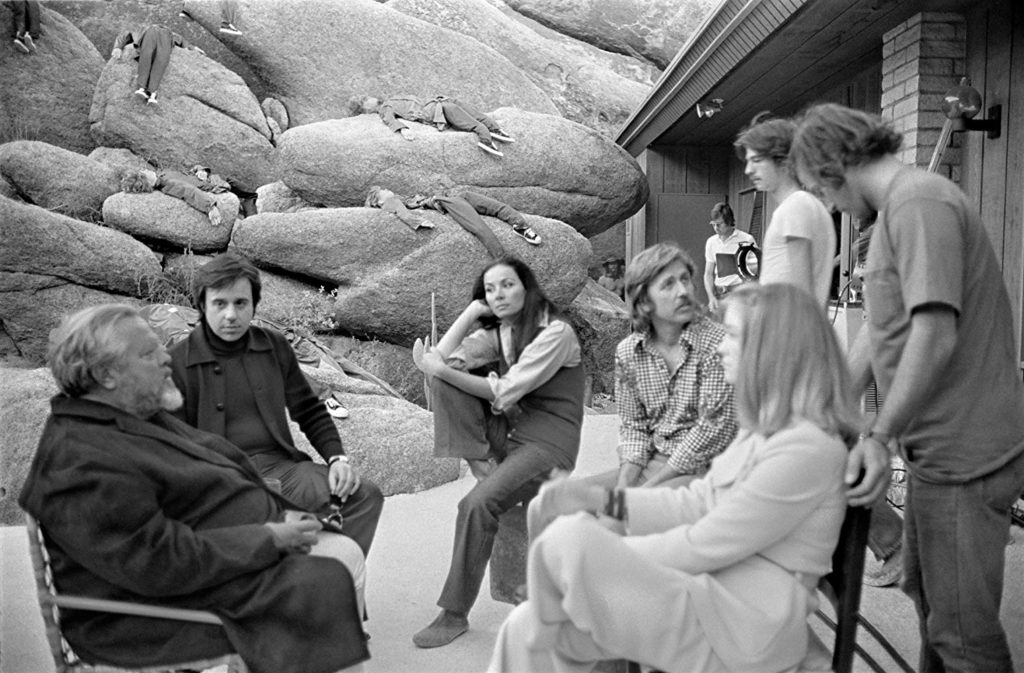

Some background and context is necessary: In 1970, Welles returns to Hollywood after 15 years of exile, hoping to make a splashy comeback with The Other Side of the Wind. It didn’t work that way for the genius director, who at age 26 made what’s considered to be by many critics the best American film ever made, Citizen Kane. Form the start, Welles was Hollywood’s enfant terrible, recognized as brilliant but “difficult” filmmaker, which led, among other factors, to his exile to Europe, and to a status that labeled him a martyred victim of the system.

Shot in an unconventional style, in both color and black-and-white, Welles’ satire contains a narrative-within narrative, a film that’s replete with references to both Classic Hollywood Cinema and Avant-Garde European Art Film, specifically Antonioni’s films, Blow-Up and Zabriskie Point.

The presence of real-life directors, American and foreign, representing a wide array of strategies and styles–from John Huston to Paul Mazursky to Claude Chabrol to Henry Jaglom–adds layers of self-reflexivity and intertextuality; you keep thinking of the would be future of the all the dramatic persona. For example, Peter Bogdanovich, who plays a major role in Other Side of the Wind, was bac then a critic and programmer, but in the next year, he would become a major director, after making a striking debut with the Oscar-winning film, The Last Picture Show.

In the “new” film, John Huston plays Jake Hannaford, an aging, egomaniac Hollywood director (possibly modeled on Welles and Huston himself) who was killed in a car crash on his 70th birthday. (Ironically, Welles himself died in 1985, when he was 70!). Just before his death, Hannaford was trying to revive his career with a sensationalistic film, which contains gratuitous sex scenes and graphic violence, all underlying very strong Freudian association (in the text and also subtext).

At the time of Hannaford’s party, this trashy faux art picture, titled Other Side of the Wind, has been left unfinished after its star, John Daly, stormed off the set. A screening of some parts of the unfinished feature is arranged to get extra-financial backing from studio boss Max David. Since Hannaford is absent, former child star Billy Boyle makes an impossible effort to describe the film’s contents. Intercut with the main thread are scenes about various groups setting out for Hannaford’s celebration at his Arizona ranch, including his young protégé and bright cineaste Otterlake (Bogdanovich), and former lover and actress in one of Hannaford’s film, played by the lovely Lili Palmer.

Obnoxious reporter Mr. Pister is thrown out of Hannaford’s car after infuriating him. Stranded in the desert, unfazed, he gets on a bus that takes crew members and journalists—including Mercedes McCambridge–to the party.

Most journalists are asking invasive, too personal questions about Hannaford’s bi-sexuality, since in public, he has always displayed charismatic macho persona a la Hemingway/Hawks/Fleming. Hannaford is also notorious for seducing his actors’ wives and girlfriends.

Most notable is the absence of John Dale, the androgynous-looking, leather-clad star, whom Hannaford had discovered when he attempted suicide by jumping into the ocean off Mexico.

Meanwhile, scenes from the film are shown at a private screening room. Hannaford, drunk and out of control, breaks down, asking Otterlake’s help to revive his flagging career, desperately trying to sober up.

A power outage interrupts the screening, but the party continues by lantern-light, eventually moving to empty drive-in Arizona.

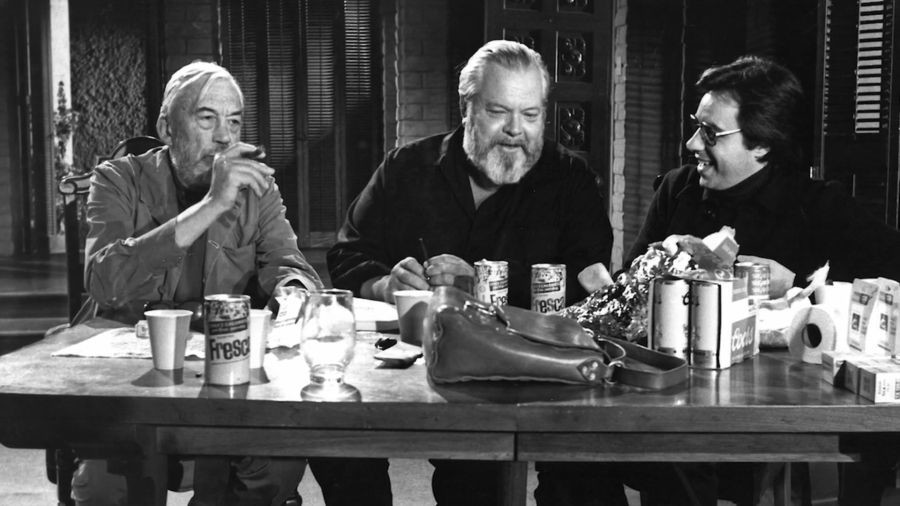

Orson Welles (1915 – 1985), American actor, producer, writer and director. (Photo by Central Press/Getty Images)

When journalist Juliette Riche (Susan Strasberg, daughter of the famous Actors Studio head, Lee Strasberg) persists in asking irritating questions, the already angry (and as usual drunk) director assaults her violently by smacking her face–to the utmost shock of the other observers.

Numerous technicians and archivists have worked hard on the restoration to lend it coherence and meaning. Occasionally, notes onscreen inform us about scenes and shots still missing. End result is a sporadically involving, intermittently dazzling feature, but ultimately a movie that remains a mystery puzzle, a curio item, and in some ways, stull unfinished, or not fully realized.

I can only guess what the movie would have looked like if Welles himself finished it. But I highly recommend that you see it: We spectators–and film history–owe this debt to one of the world’s greatest filmmakers.

Speak Your Mind