The 2019 Oscar telecast–hostless this year–is broadcast live on Sunday, February 24, 5p.m. on ABC.

In the next few weeks, we are running reviews of the worst winners of the Best Picture–chronologically.

Hey, don’t get upset! It’s a matter of taste, and we all love some bad movies, not to mention the fact that a flawed picture might still have some good moments, a powerful performance, impressive cinematography, melodic score, stirring visual or sound effects.

Below please find the list of bad winners thus far:

The first bad film to win the Best Picture is Broadway Melody (1929).

The second bad film to win is: Cimarron (1931).

The third bad film to win is: The Great Ziegfeld (1936).

The fourth bad film to win is: Mrs. Miniver (1942).

The fifth bad film to win is: The Greatest Show on Earth (1952)

The sixth bad film to win is: Around the World in 80 Days (1956)

——-

Kramer Vs. Kramer: Launching a Cycle of Family Melodrama

The reentrance of the family dramas into mainstream Hollywood cinema was gradual, with such romantic melodramas as The Turning Point in 1977, or Paul Mazursky’s socially relevant comedy An Unmarried Woman in 1978.

But it was Robert Benton’s Kramer Vs. Kramer, the 1979 Best Picture Oscar-winner, which gave legitimacy and definition to the new cycle of family pictures.

This family cycle lasted about four years, which is the average duration of a film cycle. During that time, two other films won the Best Picture, Ordinary People and Terms of Endearment. And five others were nominated for the top award, Breaking Away (1979), Coal Miner’s Daughter (1980), On Golden Pond (1982) Tender Mercies (1983), and Places in the Heart (1984), which was also directed by Benton.

Like other films which kicked off new cycles, no one associated with Kramer Vs. Kramer‘s production had initially expected such an extraordinary commercial success. Indeed, the film’s carefully designed advertising campaigns, using different posters for different target audiences, prove this point.

Based on Avery Corman’s novel, Kramer Vs. Kramer was a timely film, describing the confusion of many women who wanted to establish a firm identity, independent of their roles as wives and/or mothers and/or daughters.

The film was nicely shot on location, in Manhattan, by Cuban-born cinematographer Nestor Almendros.

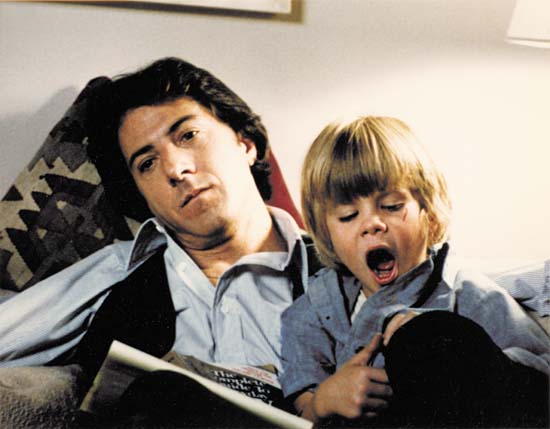

However, relevant subject matter aside, the film’s best asset was its prestige A-list cast, headed by Dustin Hoffman and Meryl Streep as the splitting couple, Justin Henry as their son, and Jane Alexander, as their sympathetic neighbor.

All four were nominated for their performances, with Hoffman and Streep winning Best Actor and Best Supporting Actress, respectively.

The 1979 writing awards were divided between Kramer Vs. Kramer, which won Best Adapted Screenplay, and Breaking Away, Peter Yates’s family comedy set in working class Bloomington, winning the Original Screenplay for Steve Tesitch.

Meryl Streep won a supporting Oscar in the role of Joanna Kramer in Kramer Vs. Kramer, a young woman who walks out on her self-absorbed husband, leaving him the responsibility of raising their 6-year-old son alone.

She is depicted as a confused woman, deeply dissatisfied with her mother-wife chores, but not as a career woman. She has a profession, but her dilemmas are not confined to career frustrations.

First Scene:

There is a close up, in profile, of Joanna Kramer (Meryl Streep), bidding farewell from her son Billy, who is in bed. In the next scene, she is seen packing her suitcase. When she first tells her husband Ted (Hoffman) that she is leaving him, he thinks “it’s a joke.”

Taking with her only $2,000, she heads to the elevator, while he rushes after her. “I’m not good for him, I have no patience, and I don’t love you anymore.” Viewers have seldom heard such an honest and emotionally raw confession from a woman, who’s a young mother. (In most Hollywood movies, it’s the husband-father who is no good for his family, and he is the one who leaves–or asked and forced to leave).

Kramer Vs. Kramer was the first major Hollywood movie to deal with a married woman who deserts her family in order “to find herself,” to regain her self-worth. Furthermore, in sharp departure from previous cinematic conventions, she willingly gives up her son, even after winning a cruel custody battle, telling her ex-husband: “I came here to take my son home, and I realized he already is home.”

Streep’s Joanna Kramer represented a new screen heroine, a woman who is concerned not only with her career, but also with asserting herself as a worthy human being, a femme whose social status is neither based nor dependent on her marital and familial roles.

The movie has also helped changing the traditional image of the husband-father, played by Dustin Hoffman, who won Best Actor. Ted Kramer starts as a tense, egotistic advertising executive, so engrossed in his career that he neglects the emotional needs of his family and forbids his wife to work. But he is capable of self-improvement, and, by the film’s end, Ted is transformed into a loving, caring father who has learned the lessons of parenthood.

Looking back, Kramer Vs. Kramer was too much of a message picture, a soap-opera melodrama, which suggested that a male can be a good parent, too, when under pressure and driven with the right motivation.

Benton’s blatantly obvious film–everything is spelled out for the audience, including a banal courtroom sequence–is artistically one of the weakest features to have won the Best Picture Award.

One of the deceptive posters of the film, which is actually about a divorcing coupe who can’t stand each other.

One of the deceptive posters of the film, which is actually about a divorcing coupe who can’t stand each other.

Oscar Nominations: 9

Picture, produced by Stanley R. Jaffe

Director: Robert Benton

Screenplay (Adapted): Robert Benton

Actor: Dustin Hoffman

Supporting Actress: Meryl Streep

Supporting Actress: Jane Alexander

Supporting Actor: Justin Henry

Cinematography: Nestor Almendros

Film Editing: Jerry Greenberg

Oscar Awards: 5

Picture

Director

Screenplay

Actor

Supporting Actress

Oscar Context:

In 1979, two movies received 9 nominations: Kramer Vs. Kramer, which won five Oscars, including Best Picture, and Bob Fosse’s dazzling musical, All That Jazz (a better movie than Kramer on any level), which received four technical awards.

The other three nominees were Coppola’s Vietnam epic “Apocalypse Now,” the comedy “Breaking Away,” and the socially-conscious drama “Norma Rae,” for which Sally Field received her first Best Actress Oscar.

Credits:

Released by Columbia (Stanley Jaffe Productions)

Speak Your Mind