On August 24, 1944, after three weeks of shooting, The Clock, a romantic drama starring Judy Garland, was shut down. Judy and her director Fred Zinnemann didn’t get along and the footage was vastly disappointing.

Judy was desperately eager to make the picture, but MGM’s Louis B. Mayer saw no point in continuing under those conditions. In a last effort to keep the project alive, Judy turned to Minnelli.

Robert Nathan and Joseph Schrank’s screenplay had interesting shadings, capturing the romantic mood of Paul and Pauline Gallico’s original story. But what Zinnemann shot didn’t play well onscreen, and it was even confusing.

Worse, the footage lacked consistence: Each scene looked as if it had come from a different picture. Minnelli could see why Metro had canceled the project. A gentleman to the core, he thought that he could make it work, but would not touch it without Zinnemann’s collegial approval.

Some of the exteriors, shot by a second unit in New York, were used in the new version, but all the intimate footage was scrapped.

Moreover, except for the main stars, Judy and Robert Walker, the only other carryover from the original shoot was the Penn State set, where the couple meets, embarks on a weekend courtship, and then parts. Scrapping all the footage shot, Minnelli started afresh.

New York City as a Character in Film

His idea was to make Manhattan an integral character to the story, which was ambitious, considering that the entire film was shot in Culver City. To create the required atmosphere, backgrounds shot by location crew were combined with studio footage. Watching The Clock, the viewers were made aware of New York City as a modifying influence on the relationship of the couple.

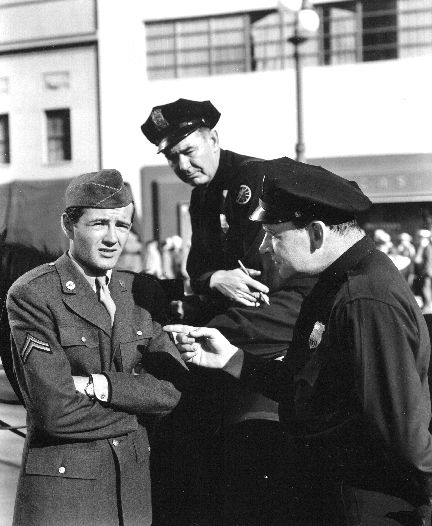

Several incidents in the script needed revision. In a scene set by the boat pond in Central Park, Walker befriends a young boy who’s helping him rig the sails of a boat. The boy is convinced that his boat will be of no service in the War effort, but Walker tells him that he is mistaken. When the boy falls into the pond, and a policeman wants to arrest him for swimming, Walker and Judy pretend to be his parents. Finding this trite, Minnelli decided that when Walker attempts to befriend the boy, he would get a kick in the shins for his trouble.

Walker’s character’s problems with children became one of the films leitmotifs. Other changes were also introduced to make the love affair more credible, and in tune with the surrounding characters and situations. Minnelli kept the film’s good parts while altering the weak ones. He developed New York City as the film’s third major character. Though the City’s landmarks were essential to the story, it was decided to shoot everything on a sound stage. It was too impractical to manage thousands of passengers at Penn Station, and it saved a lot of money. With the country still at War, the studios were under extreme scrutiny about their budgets and expenditures.

For this movie, Minnelli relied on his vivid memories of New York. Based on photographs, the City’s sites were recreated and then shot as backdrops via rear projection, with the live action placed in front of it. In one scene, Minnelli blew up a small photo of Rodin’s statue, The Thinker, and placed in on the edge of a plate. The film was so emotionally involving that critics and audiences overlooked its fake look.

The picture opens with a crane shot of Penn State, showing hundreds of people scurrying around. It picks up a young soldier, obviously dazzled by his first visit to New York, making his way through the crowd. Minnelli opted for symmetry: At the end of the film, when Alice sees the boy off, the process is reversed. The camera now follows Judy, pans back on the boom until her figure is lost in the crowd. In between these sequences, a sweet love story unfolds.

A single scene in Central Park, established Judy as a mature actress. While Judy and Walker are talking about the sounds of the city, Minnelli shows a brief closeup of Walker but lingers much longer on Judy. Cinematographer George Folsey captured Judy’s unique face lovingly and expressively. For the first time, Judy revealed onscreen that special glow of hers. People who saw “The Clock” held that it was obvious Minnelli was deeply in love with Judy because of that scene. Not surprisingly, the shy Minnelli expressed his strongest feelings for Judy through the camera.

Minnelli shot the parting scene, which contained pages of dialogue, at the very end. A crucial decision was made on the morning of the shoot. Walker’s speech would be given to Judy; it seemed nobler for her to say it. Minnelli then staged the rest of the scene in pantomime, hoping their gestures would imply, after spending their first night together, that their marriage would endure. He instructed the couple to smile, but Walker couldn’t smile, when he discovered he would have to descend via non-existing stairs to the train below. In the midst of this emotional scene, Walker had to play the old vaudeville’s trick, lower his body as he descended, so that only his head was visible. Walker never forgave Minnelli for that humiliating bit.

Critical Reaction

When “The Clock” was released, May 25, 1945, Minnelli was overwhelmed by the positive reaction. Time magazine heaped praise: “Minnelli’s talents are so many-sided and generous that he turns even the most over contrived romanticism into something memorable. He has brought the dramatic talents of his bethrothed, Judy Garland, into unmistakable bloom. Few films in recent years have managed so movingly to combine first-grade truth with second-rate fiction.”

The film was so visually and emotionally arresting, that it even worked well without sound, as silent picture. Minnelli was particularly pleased for the praise showered on his technical command, specifically the boom shot. For the first time, the critics acknowledged specifically Minnelli’s talent with the camera, described by one reviewer as “snooping and sailing, drifting and drooping.”

Commercial Appeal

With positive reviews (decades later, it still scores 100 percent on RottenTomatoes meter), the movie became commercial successful, earning $2.8 million at the box-office. It established Judy as a reliable and bankable mature leading woman (no more collaborations with Mickey Rooney…), and reaffirmed Minnelli stature as a major director (after the huge success of his 1944 musical, Meet Me in St. Louis).

Credits

MGM

Produced by Arthur Freed.

Screenplay: Robert Nathan and Joseph Schrank, from a story by Paul Gallico and Pauline Gallico

Cinematography: George Folsey

Art Direction: Cedric Gibbons; William Ferrari

Set Decoration: Mac Alper

Music Score: George Bassman

Editing: George White

Special Effects: Arnold Gillespie and Warren Newcombe

Costumes: Irene; Milton Herwood Keyes

Recording: Douglas Shearer

Running Time: 90 Minutes

Cast:

Alice Maybery (Judy Garland)

Corporal Joe Allen (Robert Walker)

Al Henry (James Gleason)

Drunk (Keenan Wynn)

Bill (Marshall Thompson)

Mrs. Al Henry (Lucile Gleason)

Helen (Ruth Brady)

Speak Your Mind