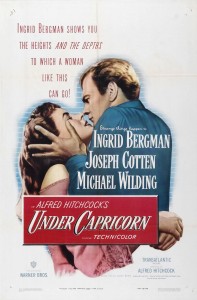

Hitchcock directed Under Capricorn, one of his weakest pictures, a British historical drama starring Ingrid Bergman, Jospeh Cotten, and Michael Wielding.

The tale concerns a couple in Australia who started out as a lady and a stable boy in Ireland, and who are now bound together by a horrible secret.

Grade: C (*1/2* out of *****)

The film is based on John Colton and Margaret Linden’s play, which in turn is based on the novel Under Capricorn (1937) by Helen Simpson. The screenplay was written by James Bridie from an adaptation by Hume Cronyn.

This was Hitchcock’s second film in Technicolor, and like his preceding color film Rope (1948), it features long takes.

The tale is set in colonial Sydney, New South Wales, Australia in the early 19th century. Under Capricorn is one of several Hitchcock films that are not typical thrillers: instead it is a mystery involving a love triangle. Although the film is not a murder mystery, it does feature a previous killing, a “wrong man” scenario, a sinister housekeeper, class conflict, emotional tension, both on the surface and underneath.

The title Under Capricorn refers to the Tropic of Capricorn, which bisects Australia. Capricornus is a constellation, Capricorn is an astrological sign dominated by the goat, a symbol of sexual desire.

In 1831, Sydney is a frontier town populated by rough ex-convicts of the British Isles. New Governor Sir Richard (Cecil Parker) arrives with his charming but indolent second cousin, the Honorable Charles Adare (Michael Wilding).

Charles, who is hoping to make his fortune, is befriended by gruff Samson Flusky (Joseph Cotten), a prosperous businessman who was a transported convict, apparently a murderer. After exhausting the legal limits of land owning, he wants Charles to buy land and then sell it to him for profit so that he can accumulate more territory.

Though the Governor orders him not to go, Charles attends a dinner at Sam’s house. He discovers that he already knows Sam’s wife, Lady Henrietta (Ingrid Bergman), an aristocrat who was good friend of Charles’s sister when they were children in Ireland. Lady Henrietta, an alcoholic, is now socially shunned.

Sam invites Charles to stay at his house, hoping to cheer up his wife, who is on the verge of madness. The housekeeper, Milly (superbly played by Margaret Leighton), has completely taken over the the household. Moreover, she secretly feeds Lady Henrietta alcohol, scheming to destroy her and then win Sam’s affections.

Gradually, Charles restores Henrietta’s self-confidence, and they become closer, leading to a passionate kiss. Henrietta explains that she and Sam are bound together profoundly. When she was young, Sam was a handsome stable boy. Driven by desire, they ran away and married at Gretna Green.

Henrietta’s brother, furious that she had paired up with a lowly servant, confronted the couple and shoots at them but missed; in retaliation, Henrietta shoots her brother fatally.

After Sam made false confession in order to save her, he was sent to the penal colony in Australia. Henrietta followed him and waited seven years in poverty for his release.

After listening to Milly’s greatly exaggerated stories of what Charles did in Lady Henrietta’s bedroom, Sam orders Charles to leave.

Taking Sam’s favorite mare in the dark, Charles has a fall and the horse breaks a leg. Sam has to shoot her dead and, in a subsequent struggle over the gun, seriously wounds Charles. Sam will now be prosecuted again for attempted murder.

At the hospital, Henrietta confesses to the Governor that Sam was wrongly accused of crime, and that she was the one who shot killed her brother. By law, she should be deported back to Ireland to stand trial.

Milly, still plying Henrietta with drink, is using a shrunken head to fake hallucinations. She then attempts to kill Henrietta with overdose of sedatives. However, caught in the act, she is ordered out in disgrace.

The Governor, Sir Richard, arrests Sam, who is charged with the attempted murder of Charles. Sir Richard ignores Henrietta’s claim that Sam is innocent of both crimes. However, Charles decides to bend the truth, stating that there was no confrontation, and no struggle over the gun; it was an accident.

In the end, Sam and Henrietta are seen smiling, bidding farewell to Charles, who’s going back to Ireland.

The film was co-produced by Hitchcock and Sidney Bernstein for their short-lived production company, Transatlantic Pictures, and released through Warner.

It was Hitchcock’s second film in Technicolor, using 10-minute takes, similar in structure to his previous film, Rope (1948).

The use of long takes in Under Capricorn promotes elements of film’s meaning, such as inaccessible space in the gothic house, the form in which characters inhabit their past, the gaze that cannot, or must meet another’s.

Cast

Ingrid Bergman as Lady Henrietta Flusky, old friend of Charles’ sister

Joseph Cotten as Samson “Sam” Flusky, businessman and Henrietta’s husband

Michael Wilding as Hon. Charles Adare, second cousin of the governor

Margaret Leighton as Milly, Flusky’s scheming housekeeper

Cecil Parker as the new Governor of New South Wales, Sir Richard

Denis O’Dea as Mr. Corrigan, Attorney General

Jack Watling as Winter, Flusky’s paroled butler

Harcourt Williams as the Coachman

John Ruddock as Mr. Cedric Potter, bank manager

Bill Shine as Mr. Banks

Victor Lucas as the Rev. Smiley

Ronald Adam as Mr. Riggs

Francis de Wolff as Major Wilkins

G. H. Mulcaster as Dr. Macallister

Olive Sloane as Sal

Maureen Delany as Flo

Julia Lang as Susan

Betty McDermott as Martha

Martin Benson as Man Carrying Shrunken Head (uncredited)

Lloyd Pearson as Land Agent (uncredited)

Credits

Director – Alfred Hitchcock

Writing – James Bridie (screenplay), Hume Cronyn (adaptation)

Cinematography – Jack Cardiff

Art direction: Thomas N. Morahan (production design); Philip Stockford (set dresser)

Technicolor color director – Natalie Kalmus

Costume design – Roger K. Furse

Assistant director – C. Foster Kemp

Production management: Fred Ahern; John Palmer (unit manager)

Editor: A. S. Bates

Camera Operators: Paul Beeson, Ian Craig, David MacNeilly, Jack Haste

Sound: Peter Handford

Continuity: Peggy Singer

Makeup artist: Charles Parker

Music: Richard Addinsell (musical score), Louis Levy (musical director)

Hitchcock cameo:

A signature which occurs in three-quarters of Hitchcock’s films,

In this film, he can be seen in the town square during a parade, wearing a blue coat and brown hat at the beginning of the film. He is also one of three men on the steps of the Government House 10 minutes later.

Hitchcock told Truffaut that Under Capricorn was such a failure that Bankers Trust Company, which financed, repossessed the film. As a result, it was unavailable to the public until the first US network TV screening in 1968.

Playwright James Bridie, who wrote the screenplay, is famous for his Biblical plays, such as Jonah and the Whale.

Cecil Parker’s character Sir Richard may be a representation of General Sir Richard Bourke, Governor of New South Wales from 1831 to 1837.

The film earned $1.21 million domestically and $1.46 million in foreign territories.

The audience expected Under Capricorn to be a thriller, which it was not. The plot was a domestic love triangle with few thriller elements. However, the public reception might have been tarnished by the revelation in 1949 of Ingrid Bergman’s adulterous relationship with the married Italian director Roberto Rossellini.

John McCarten of the New Yorker wrote that “this picture simultaneously succeeds in insulting the Australians, the Irish, and the average intelligence.”

Richard L. Coe of The Washington Post wrote: “The triangle performances are splendid, but the lines and situations the three principals are called upon to face are trite indeed … Jame’s Bridie’s script, from a Helen Simpson novel adapted by Hume Cronyn, has little to be proud of, is indeed unintentionally hilarious at times.”

The Monthly Film Bulletin was also negative: “The story is not enlivened by any qualities in the dialogue, which is crude and frequently stilted, or in the direction, which surely represents the nadir of Hitchcock’s present period. It is extraordinary that this director, responsible for some of the most brilliant British films of the thirties—lively, fast, and full of incident—should return to this country from Hollywood for the sake of a ponderous novelette, which even more than Rope shows a preoccupation with complicated camera movements of no dramatic value whatsoever.”