In 1937, William Dieterle’s The Life of Emile Zola was nominated for the largest number of awards, 10.

The movie won three major awards: Best Picture (producer Henry Blanke), Screenplay (Heinz Herald, Geza Herczeg, and Norman Reilly Raine), and Supporting Actor to Joseph Schildkraut, playing the role of the wrongly accused Jewish Captain, Alfred Dreyfus.

Viewers who saw the film at the time talked for a long time about the powerful scene, in which the anguished French novelist, previously censured by the government and public for his audaciously realistic novels (“Nana” among them), takes his pen in hand and declares, “J’Accuse!” upon which audiences cheered and applauded out of their seats.

Our Grade: B (*** out of *****)

As expected, the movie is replete with liberal speeches. Addressing the courtroom, Zola states: “Not only is an innocent man crying out for justice, but more, much more–a great nation is in desperate danger of forfeiting her honor!” So do not take upon yourself a fault, the burden of which you will forever bear in history! A judicial blunder has been committed. The condemnation of an innocent man induced the acquittal of a guilty man, and now today you are asked to condemn me because I rebelled on seeing our country embarked on this terrible course.”

Defending Dreyfus in court, he exclaims: “At this solemn moment, in the presence of this tribunal which is the representative of human justice, before you gentlemen of the jury, before France, before the whole world—I swear that Dreyfus is innocent by my 40 years of work, by all that I have won, by all that I have written to spread the spirit of France, I swear that Dreyfus is innocent! May all that melt away!—May my name perish if Dreyfus be not innocent.

Defending Dreyfus in court, he exclaims: “At this solemn moment, in the presence of this tribunal which is the representative of human justice, before you gentlemen of the jury, before France, before the whole world—I swear that Dreyfus is innocent by my 40 years of work, by all that I have won, by all that I have written to spread the spirit of France, I swear that Dreyfus is innocent! May all that melt away!—May my name perish if Dreyfus be not innocent.

At the end, Morris Carnovsky offers a grand, pompous eulogy of Zola in the film’s last lines: “France is once again today a land of reason and benevolence, because one of her sons through an immense work and great action gave rise to a new order of things based on justice and the rights common to all men! Let’s not pity him, because he suffered and endured. Let us envy him! Let us envy him because his great heart won him the proudest of destinies. He was a moment in the conscience of man.

Despite its grim subject, courtroom scenes, and long speeches, “Life of Emile Zola” became a huge success, both critically and commercially, serving as a model for other social-problems pictures, before, during and after WWII.

Despite its grim subject, courtroom scenes, and long speeches, “Life of Emile Zola” became a huge success, both critically and commercially, serving as a model for other social-problems pictures, before, during and after WWII.

Paul Muni’s “specialty” in Hollywood was portraying extraordinary men in a series of Warner biopics, including Louis Pasteur, Benito Juarez, Pierre Radisson (the French explorer), Joseph Elsner (Chopin’s teacher), Napoleon, and Schubert.

Had Paul Muni not won the Best Actor the previous year, for another biopicture, “The Story of Louis Pasteur,” he would have received the Oscar for his portrayal of the French writer, Emile Zola, who exposed anti-Semitism in the French government.

Had Paul Muni not won the Best Actor the previous year, for another biopicture, “The Story of Louis Pasteur,” he would have received the Oscar for his portrayal of the French writer, Emile Zola, who exposed anti-Semitism in the French government.

Reviewing The Life of Emile Zola, one critic suggested that, “Along with Louis Pasteur, it ought to start a new category: The Warner crusading films, costume division.”

Detailed Plot

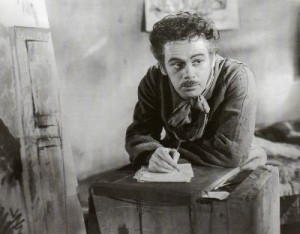

Struggling writer Émile Zola (Paul Muni) shares a Paris attic with his friend painter Paul Cézanne (Vladimir Sokoloff). An encounter with a street prostitute (Erin O’Brien Moore) hiding from the police inspires his first bestseller, Nana, an exposé of Parisian underside life.

Struggling writer Émile Zola (Paul Muni) shares a Paris attic with his friend painter Paul Cézanne (Vladimir Sokoloff). An encounter with a street prostitute (Erin O’Brien Moore) hiding from the police inspires his first bestseller, Nana, an exposé of Parisian underside life.

After publishing other successful novels, Zola becomes rich and famous, marries Alexandrine (Gloria Holden) and settles down. His friend Cézanne, still poor and unknown, reproaches him for becoming complacent, leaving his zeal behind.

The French secret agent steals a letter sent to a military officer in the German embassy, which confirms there is a spy within the top French staff. The army commanders declare the Jewish Captain Alfred Dreyfus (Joseph Schildkraut) as the traitor and he is court-martialed and imprisoned

However, when Colonel Picquart (Henry O’Neill), the new chief of intelligence, discovers evidence implicating as the spy Major Walsin-Esterhazy (Robert Barrat), he is ordered by superiors to remain silent to avert official embarrassment. Dreyfus’s loyal wife Lucie (Gale Sondergaard) pleads with Zola to take up her husband’s cause. Zola is reluctant, but changes his mind when she brings new evidence, a letter is published in the press accusing the army of cover-up.

However, when Colonel Picquart (Henry O’Neill), the new chief of intelligence, discovers evidence implicating as the spy Major Walsin-Esterhazy (Robert Barrat), he is ordered by superiors to remain silent to avert official embarrassment. Dreyfus’s loyal wife Lucie (Gale Sondergaard) pleads with Zola to take up her husband’s cause. Zola is reluctant, but changes his mind when she brings new evidence, a letter is published in the press accusing the army of cover-up.

Zola hires the shrewd attorney Maitre Labori (Donald Crisp), but he is found guilty and sentenced to a year in prison. Zola is forced to flee to England in order to continue the campaign on behalf of Dreyfus.

A new administration finally admits that Dreyfus is innocent, and those responsible for the cover-up are dismissed or commit suicide; Walsin-Esterhazy flees the country in disgrace. Ironically, Zola dies of accidental poisoning the night before Dreyfus’s public exoneration.

Characteristic of Hollywood movies of the era, which wished to be liberal but were fearful of direct attacks on Hitler or references to Nazism and anti-Semitisim, The Life of Emile Zola never mentions explicitly the word “Jew.” According to several American scholars (prime among them Thomas Doherty), it was studio head Jack Warner, a self-proclaimed proud Jew, who ordered the word ‘Jew’ (or anti-Semitism) to be deleted from the text.

Oscar Alert

Nine other movies competed with “The Story of Emile Zola” for Best Picture, including Leo McCarey’s marital comedy “The Awful Truth,” with six nominations, and Gregory La Cava’s “Stage Door,” with four. The other nominees were: William Wyler’s social drama set in a New York City slum, “Dead End,” Frank Capra’s utopian comedy “Lost Horizon,” and Henry King’s adventure “In Old Chicago.”

The remake, “I Accuse,” in 1958, is a poor feature.

Cast

Paul Muni as Émile Zola

Gloria Holden Alexandrine Zola

Gale Sondergaard as Lucie Dreyfus

Joseph Schildkraut as Captain Alfred Dreyfus

Donald Crisp as Maitre Labori

Erin O’Brien-Moore as Nana

John Litel as Charpentier

Henry O’Neill as Colonel Picquart

Morris Carnovsky as Anatole France, Zola’s friend and supporter

Louis Calhern as Major Dort

Ralph Morgan as Commander of Paris

Robert Barrat as Major Walsin-Esterhazy

Vladimir Sokoloff as Paul Cézanne

Grant Mitchell as Georges Clemenceau

Harry Davenport as Chief of Staff

Robert Warwick as Major Henry

Charles Richman as M. Delagorgue

Gilbert Emery as Minister of War

Walter Kingsfordas Colonel Sandherr

Paul Everton as Assistant Chief of Staff

Montagu Loveas M. Cavaignac

Frank Sheridan as M. Van Cassell

Lumsden Hare as Mr. Richards

Marcia Mae Jones as Helen Richards

Florence Roberts as Madame Zola, Zola’s mother

Dickie Moore Pierre Dreyfus, Captain Dreyfus’s son

Rolla Gourvitch as Jeanne Dreyfus, Dreyfus’s daughter