Arthur Freed owned the stage rights for a musical adaptation of Kismet, which was a smash hit on Broadway. Considering that it was sort of an Arabian Nights kitschy pastiche, Kismet had already enjoyed a long life on stage and screen.

The original drama, by English playwright Edward Knobloch, had dazzled theatergoers before WWI. In 1944, MGM created a lavish remake as a Ronald Colman vehicle, with Dietrich as the sultan’s mistress. Nine years later, composers Robert Forrest and George Wright turned the straight play into a stage musical.

In 1954, Alan J. Lerner was asked to write the screenplay and to compose the score with Schwartz. George Forrest and Robert Wright had previously done the successful Edward Grieg’s “Song of Norway,” adapted from themes by Alexander Borodin. Most theater critics thought that Kismet was kitsch, but a newspaper strike prevented the nasty reviews from spreading to the public, so they had no effect on the shows standing. The musicals principal merits were Alfred Drake’s star turn and the melodic score. Songs like “Stranger in Paradise” and “Baubles, Bangles, and Beads,” dominated the airwaves, and the show ran for two seasons.

When Freed first talked to Minnelli about Kismet, Minnelli said: “I hated the show, I don’t want to do it!” Freed was astonished by his strong decline. Minnelli had to explain that he hated the show because it was corny and witless. Freed had never heard Minnelli express his opinion so harshly and bluntly. A few days later, Minnelli was summoned to Schary’s office for a conversation behind closed doors. Ten minutes later, when Minnelli left the office, he had lost the battle on Kismet, but for a good cause. In return for Kismet, Minnelli was promised to direct the Van Gough project, now titled Lust for Life, with larger than usual budget, on-location shooting, and promises of unrestricted artistic freedom.

The Baghdad-set Kismet is a fable about how the magical powers of the street poet Hajj are abused by the scheming Wazir to advance his own power. The poet is an opportunist who fixes things so that his daughter Lalume can wed the Caliph and he can be sent to a romantic oasis.

In his casting, Minnelli was forced to rely on MGM contract players and second bananas. The baritone Howard Keel was chosen to play Hajj, Lalume went to Dolores Gray, whose screen test Minnelli himself had shot; the young Caliph and Hajj’s daughter Marsinah were played by Vic Damone and Ann Blyth. The villain was played by Sebastian Cabot, a good British stage actor who was unknown to American audiences.

Jack Cole was assigned to choreograph Kismets musical numbers, based on his work on the Broadway and London stage productions. Minnelli and Cole have known each other well from their days at the Radio City Music Hall, but they had different tastes that needed to be consolidated into a unified vision.

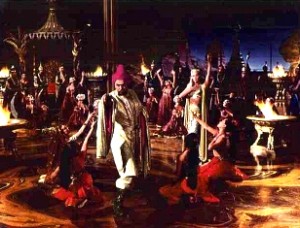

Visually, Minnelli opted for an almost monochromatic look, like Olsen and Johnson in Baghdad but very beautiful and chic.” The model for the film was “The Pirate, a sort of fairy tale done tongue-in-cheek. The film was meant to look like a Persian painting with surreal skies and gold clouds.

While Minnelli worked with Preston Ames on the sets and with Tony Duquette on the costumes, Cole began rehearsing the dances. Most of the songs from the Broadway show were retained, including “Stranger in Paradise, Baubles, Bangles and Beads, The Olive Tree, and This Is My Beloved. Nineveh, the first dance number Cole choreographed, was exciting, but it caused a rift between Green and Cole, which Freed solved in Greens favor.

By early 1955, Minnelli was already in pre-production on Lust for Life, a film he was eager to make. Minnelli lost interest in Kismet as soon as the picture went into production, on May 23, 1955.

As a result, what was meant to be a farcical fairytale became heavy-handed, grim, and listless. There was no real fun in the movie. Even the usually vital Jack Cole failed to inject sophisticated humor into his dance routines. Bored, restless, unpleased with the cast, and already preoccupied with Lust for Life, Minnelli paid more attention to the decor than to the performers, most of whom he disliked.

Minnelli was given half of his usual time to direct Kismet. He embarked on the most demanding schedule he had faced since American in Paris, planning two films at the same time, and then shooting them back-to-back on two different continents. Before filming Kismet, Minnelli first had to go to Arles for Lust for Life, to shoot the orchards in spring blossom

Minnelli relied on craftsmen who understood instinctively his method of work. Preston Ames did the sets, Tony Duquette, the sculptor-decorator, designed the costumes, Adrienne Fazan supervised the editing, and Joseph Ruttenberg the cinematography.

Kismet began shooting on May 23, 1955 and ended two months later. Once again Minnelli was drafted to concoct glitzy tableaux out of routine material, and third-rate thespian. As always, Minnelli relied on his professionalism, though he couldn’t conceal his contempt for the corny material.

Usually, Minnelli was meticulous in working out every camera composition, but this time, as a result of carelessness and rush, he uncharacteristically printed out the first or second takes. The timetable was too tight to afford rehearsals with the actors, who soon were exhausted by the pace. Four days before Kismet was completed, Minnelli flew to London to join Houseman, who was in Europe scouting locations for Lust for Life.

Basically, in Kismet, Minnelli did a literal translation of the stage play, with the actors reciting stiff Arabian syntax. Most musical numbers end with Dolores Gray or the showgirls posing. The film was made for the undemanding fans of exotica. Here and there, Minnelli displays personal touches, but they are trivial, like throwing a yellow silk across the silver screen.

Only one sequence, Night of My Nights, in the dusk of the Caliph’s nuptial, was spectacular. White steeds and courtiers in pastel silks parade across the screen, bearing a cornucopia of Duquette’s swankiest accessories: sparklers, canopies, and temple altars. The scene pays homage to Minnelli’s own costumes parades early on in his career, the Marshall Field’s display windows, and the “Scheherazade Suite,” his first art-direction job at Radio City Music Hall.

Ten days before the picture was completed, Minnelli had to leave for France to start shooting Lust for Life. Stanley Donen was brought in to finish Kismet. Production closed on July 22, 1955, at a cost of $2,692,960. The studio held two sneak previews, which yielded only moderate response. One preview card noted that Kismet is as good as Lana Turner’s pictures! whatever that meant.

Kismet premiered on October 8, 1955 at Radio City Music Hall, on a double bill with the annual Nativity Pageant. The New York press response was no more than cordial. The box office receipts were disappointing, about $2,920,000.

Kismet became one of Minnelli’s least personal films, and in the view of this writer, one of his two or three weakest pictures. It was as if Minnelli was using ideas from his scrapbook but without his distinctive signature or his soul.

Cast:

Hajj, the Poet (Howard Keel)

Marsinah (Ann Blyth)

Lalume (Dolores Gray)

Caliphe (Vic Damone)

Omar (Monty Woolley)

Wazir (Sebastian Cabot)

Jawan (Jay C. Flippen)

Chief policeman (Mike Mazurki)

Hasan-Ben (Jack Elam)

Police subaltern (Ted de Corsia)

Zubbediya (Julie Robinson)

Credits

Produced by Arthur Freed

Assistant director: William Shanks

Screenplay: Charles Lederer, Luther Davis, adapted from the musical play; book by Lederer and Davis, based on the novel by Edward Knobloch

Music and lyrics by Robert Wright and George Forrest, adapted from themes by Aleksander Borodin: “Stranger in paradise,” “Rahadlakum,” “And This Is My Beloved,” “Sands pof Time,” Not Since Ninevah,” “Baubles, Bangles, and Beads,” “Fate,” “Bored,” Gesticulate,” “Night of My Nights,” “The Olive Tree.”

Cinematography: Joseph Ruttenberg

Art Direction: Cedric Gibson, Preston Ames

Set Decoration: Edwin B. Willis; Keogh Gleason

Musical supervision: Andre Previn, Jeff Alexander.

Orchestrations: Conrad Salinger, Alexander Courage, Arthur Morton, conducted by Previn

Musical staging and Choreography: Jack Cole

Editing: Adrienne Fazan

Special Effects: Warren Newcombe

Costumes: Tony Duquette

Color consultant: Charles K. Hagedon

Print process: Eastmancolor

Recording Direction: Dr. Wesley C. Miller

Vocal supervision: Robert Tucker

Hair: Sydney Guilaroff

Makeup: William Tuttle

Running Time: 113 Minutes