“Forget it, Louis. No Civil War picture ever made a nickel”–Irving Thalberg to Louis B. Mayer

“David Selznick thinks Gone With the Wind is art and will go to his grave thinking so”–Orson Welles

For many moviegoers, Gone With the Wind (GWTW) represents the pinnacle of mainstream entertainment, not to be confused with genuine artistic achievement, during Hollywood’s Golden Age.

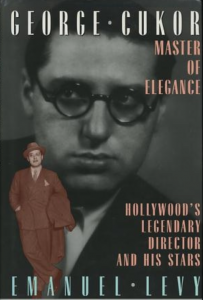

A lot has been written about GWTW, in front and behind the cameras. I explored its troubled production in my biography of George Cukor, Master of Elegance (1994). As is well known, Cukor was the original director, who worked on the film for two years before getting fired by producer David O. Selznick. Cukor did all the casting and shot some of the film’s best scenes (such as Melanie’s childbirth), which remain intact in the final version. In the biography, I tried to clear several misconceptions, such as the prevailing notion that Cukor was fired because Gable resented his homosexual director.

All of which is untrue. My evidence points to a different direction: Selznick simply didn’t like Cukor’s work, his pacing of some important episodes, his preferential treatment of Vivien Leigh. There were also conceptual differences between the two. Cukor always saw Margaret Mitchell’s book and the movie as a quintessentially women’s material. The books most loyal fans were young women. Indeed, though Gable was a bigger name than Leigh at the time, his role in the movie is smaller and less important than Scarlett’s.

Please read our review of the 2013 Best Picture, 12 Years a Slave, a totally different take on Slavery

The great critic Andrew Sarris was the first reviewer to point out that GWTW is one of the few notable exceptions to the auteur theory and its notion of directorial signature.

Indeed, it’s hard to tell whose vision this epic movie melodrama represents?

Selznick, Ben Hecht, George Cukor, Sam Wood, William Cameron Menzies all contribute to the final shape of the picture, though Victor Fleming received sole directorial credit, for which he won the Oscar. For Sarris (and others, including Orson Welles, quoted above), GWTW failed as an art work due to the incessant interferences with a project that was too big to be controlled by a single directorial style.

Artistically, GWTW is one of the most overestimated features in Hollywood’s history.

The script is as undistinguished as Mitchell’s prose. It was written by at least ten writers, resulting in a patchwork job with no coherent intelligence behind it except Mitchell’s source material.

The movie succeeded as entertainment due largely to the inspired casting of Vivien Leigh. Audiences responded to the actors mythic screen persona. Gable was already a legendary star, whereas Vivien Leigh became one after the picture, for which she won her first Oscar.

There’s strong support to Cukors conception of the film as a woman’s melodrama. Literary scholar Leslie Fiedler has claimed that Mitchell’s novel was addressed not to the mothers, but to the Daughters of America. After all, Scarlett was a modernist heroine, the eternal adolescent who’s bright, heartless, selfish, indomitable, and desirable.

GWTH begins with a prologue that seemed nostalgic in 1939, but is problematic today: “There was a land of Cavaliers and Cotton Fields called the Old South. Here in this patrician world the Age of Chivalry took its last bow. Here was the last ever seen of the Knights and their Ladies Fair, of Master and of Slave. Look for it only in books, for it is no more than a dream remembered, a Civilization gone with the wind.” GWTW laments the end of the Old World, be it real or imagined.

Against this backdrop of lost world, though, is the message that the spirit of the Old South, which is the spirit of America by association, will live on forever despite obstacles. Hope and optimism are the basic elements of survival, GWTW teaches us. This lesson is reflected in Scarlett O’Hara’s speech, which ends up the movie: “Tara! Home! I’ll go home, and I’ll think of some way to get him back. After all, tomorrow is another day!” Earlier, Scarlett is taught by her Irish father that Tara, and the land, outlast everything. Hence, GWTW perpetuated the myth of the sacredness of the Land.

GWTH was released in 1939, at a time when the U.S. was aware of the growing political unrest in Europe and its potential threat for America. Hope and optimism were needed in the face of these new threats and fears. As Americans watched the Old World of Europe crumble, they were reassured by GWTW that their American world would live on, no matter what might happen. Several critics have faulted GWTW as a reductive, hyped-up novel. There’s no denying that the film’s raw, excessive melodrama, with its shamelessly sadomasochistic elements, brought a lot of pleasure to mass audiences. Take, for example, the themes of rape and vengeance. There are no less than two attempted rapes of Scarlett, and a third successful one by her own husband. At the time, conservative male viewers suggested that a selfish and hurtful woman like Scarlett might deserve to be mistreated by Rhett.

One of the movie’s most problematic aspects is its depiction of black slaves, as the prologue states, “Here was the last ever seen of Master and of Slave.” The Mammy figure (played by Hattie McDaniel) and her younger counterpart Prissy (Butterfly McQueen) are offensively racist portrayals. While they have hearts of gold and are loyal, they’re often used for comic relief in the film. The films “Jim Crow” humor has come under attack by many black critics, including Malcolm X, who wrote in his autobiography after seeing the film, “I was the only Negro in the theater, and when Butterfly McQueen went into her act, I felt like crawling under the rug.”

Blatant Racism

The blatant racism is reflected in the pity, pathos, and condescension toward the black characters. Mitchell was not alone in this Southern literature often described Negroes as darkies who had to be handled gently like children, that is, to be commanded, praised, patted, and scolded.

Nevertheless, blacks and whites alike have made GWTW the most successful film of all-time. If the films box-office grosses are adjusted to today’s economy, GWTH could easily beat out every blockbuster, including Titanic and E.T. NBC paid $5 million for one showing of the film, then CBS paid $35 million for showing of the film over ten years. In 1984, when GWTW was first placed on the video market, it did great business, and I expect the same of Warner’s new DVD edition.

To the question posed by the film’s ambiguous ending, “Did Scarlett ever get Rhett back” an answer finally arrived in Alexandra Ripley’s novel, Scarlett: The Sequel to Margaret Mitchell’s GWTW. In 1993, Scarlett appeared as a CBS miniseries, sparking further revival of the original film. The disappointing sequel only elevated the visibility of the original.

Today, no one remembers the TV miniseries but we still cherish Gone With the Wind as one of the two or three most mythical, if enjoyable, American films ever made.

Note:

George Cukor worked on the film for two years, including conceptual design and especially casting, but was fired by producer Selznick two weeks after shooting began.