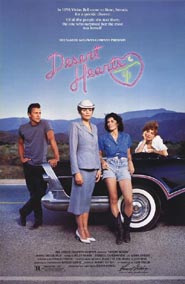

In 1986, two films by first-time directors heralded a new American gay wave: Donna Deitch’s Desert Hearts and Bill Sherwood’s Parting Glances.

(A more significant cycle, known as the New Queer Cinema, would emerge n 1991-1992).

Grade: B

Desert Hearts is set in the 1950s and concerns a love affair that grows out of two women’s search for identity. Deitch was attracted to Jane Rule’s novel, Desert of the Heart, for the simple reason that there had not been a romantic story between women in commercial cinema. When such romantic relationships are explored, they usually end up in suicide or in a bisexual triangle. Even Personal Best (1982), a gay Hollywood film which deals with a character coming to terms with lesbianism, presents the process as traumatic. Feeling that times had changed, and there could be more frank discussion of sexuality, Deitch purchased the film rights.

Deitch’s struggle to raise the $1.5 million budget took nearly four years. Unlike Sherwood, Deitch wanted a name cast, but several actresses declined to read for the lead role “on the basis of the lesbian theme,” which eventually was played by Helen Shaver. At first, Deitch kept a newsletter with donors, but eventually she was forced to sell her house to cover completion costs. It was unlikely that Sherwood or Deitch would be given the opportunity to direct, if their movies were made by the studios.

Set in 1959, the yarn revolves around Vivian Bell (Helen Shaver), an English literature professor who arrives in Reno to divorce her husband. The tall, haughty Easterner descends from the train wearing a tailored gray suit, her blonde hair gathered beneath a matching gray hat.

Desert Hearts (1986)

It’s clear from the opening shot that it’s a matter of time before the suit comes off and the hair comes down. Sure enough, at the end, Vivian lets her hair down and discovers sexual freedom. A proud, uptight lady, Vivian needs someone to liberate her, light her fire, and this woman turns out to be Cay Rivvers (Patricia Charbonneau), a lesbian daredevil who works nights as a casino cashier. Wild and fearless, Cay makes her entrance driving backwards at top speed down a narrow dirt road.

The whole narrative builds up toward the women connecting, though it doesn’t happen right away. There are confidences traded while horseback-riding, a long drive into the desert, an innocent kiss. When Vivian is asked to move out of the motel, she is angry and humiliated, but she’s single-mindedly pursued by Cay. Tired of one-night-stands, Cay is intrigued by Vivian. After several misunderstandings and soulful conversations, inhibitions fade and heated sex follows.

To film a book that was published in the 1970s required major changes, but screenwriter Natalie Cooper doesn’t provide any dark corners or shadings to the characters. The well-groomed Vivian, the Eastern stiff, is severe, standoffish and inhibited. She stays at a dude ranch, a comfortable hideaway where about-to-be divorced women sit on the porch complaining about men. Vivian remains inside, reading with her glasses on, a spinster who doesn’t know her own nature. Cay is her opposite: younger, prettier, a free spirit. By day, Cay throws pottery in a studio-shack on the ranch, which is owned by Frances, the hard-drinking mistress of her late father. Frances loves Cay as if she was her daughter, but she can’t approve of her intensely independent “lifestyle.” When Frances begins to fear she might lose Cay, she turns nasty and mean.

Unlike Parting Glances, Desert Hearts is solely concerned with the issue of coming out. One waits impatiently to see if Vivian will bed Cay, as if this decision were sufficient to sustain a whole drama. Men aren’t an issue, because they are hardly present; Vivian’s husband-professor remains safely off screen.

Cay, who’s defiantly open about her sexuality, attacks Vivian’s defenses, but it’s not clear if she’s attracted to Vivian for her brain, her success, or the thrill of the chase With so narrow a focus, the material cries out for comedy, but the movie is earnest and the dialogue stiff.

Scenes at the ranch are so dry that one wishes for the nasty humor in George Cukor’s 1939 classic comedy The Women, also set in a Reno divorce ranch.

Directed by Deitch in an impersonal style, the film follows Vivian’s denial through every hesitation, which prompted the critic David Denby to describe Desert Hearts as symptomatic of the hygienic American attitude toward sex.