Artistically speaking, “Bonnie and Clyde,” which celebrates this week the 50th anniversary of its theatrical release, may be one of the most overrated pictures in American film history.

No doubt it was one of the most important films to have come out of the studio system (it was made by Warner) in the late 1960s, a thrilling (but not major or seminal) crime-gangster tale.

Arthur Penn, who had established a name for himself in 1962 with The Miracle Worker, put everything that he knew about film language and style into the picture. End result is a vivid, intelligent, finely crafted picture which nevertheless is not too deep in its narrative or characterization.

Even so, “Bonnie and Clyde” made a big commercial and cultural splash, leaving a strong impact on a whole generation of filmmakers and heralding the birth of the New American Cinema.

Released in the same summer as Mike Nichols’ youth comedy, “The Graduate,” which is also overrated, “Bonnie and Clyde” struck a nerve with the youth generation during the height of the anti-Vietnam War movement.

Despite (or maybe because of) its controversial nature, “Bonnie and Clyde” grossed $23 million at the box office (a huge amount by that time’s standards, equivalent of about $100 million today), thus becoming Warner’s second commercial attraction, after the movie musical “My Fair Lady,” George Cukor’s Oscar winner in 1964.

Defying historical accuracy, and authenticity, the script by David Newman and Robert Benton (before he became a director) reimagined Bonnie and Clyde, the notorious criminals of the Depression era, as misunderstood rural youths. In tune with the times, they perceived them as largely sympathetic and nonconformist outlaws, who wanted a bigger share than their lot would allow in the big pie called the American Dream.

Just as innovative as the narrative structure and the characters was the film’s fast pace and stylization, Also remarkable was the variegated tone, which changes from violence and mayhem to lyrical and romantic sequences to slapstick humor, without upsetting audiences. The genre-shifting text, or rather the blend of different genres, reminded critics of one of the major contributions of the French New wave, then in high vogue, to the international cinema.

At the time, the filmmakers claimed that the bloodshed, though stylized in the extreme, was no more intense and graphic than what viewers were watching on their TV screens, with the daily reportage of the body count in Vietnam.

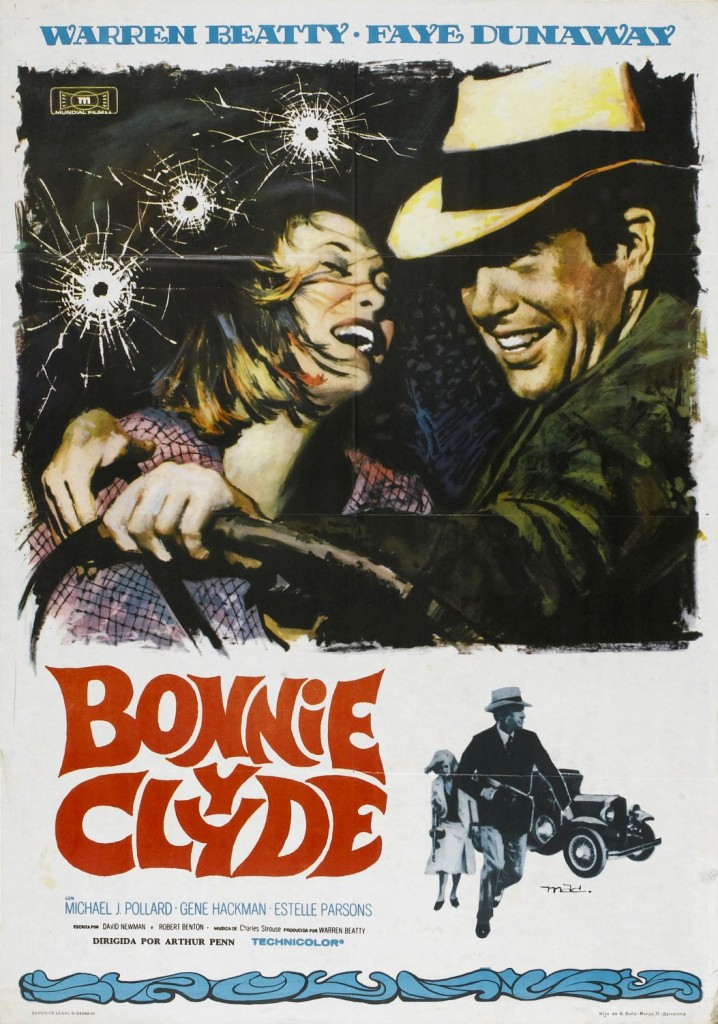

Warren Beatty and Faye Dunaway, then at their sexiest, are, of course, too glamorous for the portraiture of rural youths. But they played the couple as youth who liked to rob banksand posed for photographs in what’s an early study of the desperate need for celebrity status. One of the film’s ad campaigns stated: “They are young, they are in love.” And another proclaimed: “We rob banks, not people.”

Director Penn later said that at first, he wanted to make a realistically looking picture, based on Walker Evans photos and NRA poster, but that, ultimately, he and producer-star Beatty opted for a more warmly nostalgic, sympathetic, and stylized vision.

Ironically, “Bonnie and Clyde” was initially dismissed by serious critics as just another gangster programmer. The first review in “Time” Magazine lambasted the film in a curt, cruel review. But later on, did a complete turnabout the following week, in which their critic retracted his statements and, in an elaborate cover story, announced that “Bonnie and Clyde” was one of the most significant pictures of the decade.

In a peculiar turn of events, the movie that in some regions was marketed as an exploitation crime flick was also chosen to kick off the Montreal International Film Festival, thus beginning a new trend of films marketed for different niche audiences. Screenwriters Newman and Benton, who came from the magazine and art worlds, based their story on the life and legends of Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow, real life Depression era rural gangsters who terrorized the Southwest as they traveled about in stolen cars. The couple was accompanied by Clyde’s silent but strong brother Buck (Gene Hackman), Buck’s flighty wife Blanche (Estelle Parsons), and a zany, impish rube named C. W. Moss (Michael J. Pollard), whose father would later betray the couple and caused their deaths.

The writers also incorporated certain incidents, which, historically, happened to members of the Dillinger gang. As a result, their tale represents more of a composite portraiture of the early twentieth-century cult of the outlaw.

Penn incorporated various artistic techniques, recently developed by the French New Wave filmmakers of the early 1960s–Jean-Luc Godard, Franois Truffaut, Claude Chabrol–into his directorial approach. In this, Penn helped to further the emergence of an international cinema by cross-pollinating the techniques of the French filmmakers, bringing the devices they had initially discovered in American action films (largely B-Picture noirs) back to the new mainstream American cinema.

Instead of the serious approach of other recent rural gangster features, Penn artfully speeded up the action in key scenes, making the movie look like an old Keystone Kops slapstick comedy. The effect was disconcerting and disorienting, because he featured such techniques at moments of extreme violence (the bank holdups, the shootouts), making the most upsetting scenes look silly and even frivolous. By shooting these sequences in a style that was diametrically opposed to what audiences expected, Penn created a fresh and different viewing experience out of what could easily have been conventional scenes.

Penn also explored in an unprecedented frank way the link between sex and violence in society by concentrating on the shifting relationships between the characters. At first, Bonnie and Clyde appear to be mindless, cold-blooded killers. Significantly, in the beginning of the saga, Clyde is impotent, resisting all of Bennie’s sexual advances in favor of a close attachment to his gun. However, as he and Bonnie “mature” emotionally, they become more interested in a meaningful relationship, less concerned about robbing banks.

After Bonnie has actually learned to express herself in words, writing of their love in a crude but touching poem, the couple communicate their love physically–in the open fields. Interestingly, from that point on, they kill no one.

Critics noted that Lee Harvey Oswald, the accused assassin of President Kennedy, was reportedly impotent, and the filmmakers of “Bonnie und Clyde” reflected such a concept. Sex and violence are seen as the positive and negative aspects of a single force: When one is repressed, the other is released in devastating proportions.

As pointed out, Bonnie and Clyde was preceded by an effective advertising campaign, and the film’s popularity promptly launched a wave of nostalgia for the clothing styles and fashions of the thirties.

The movie both romanticized and idealized the criminal couple. Clyde acts with kindness toward the helpless, like the poor farmers. “Is that your money or the bank’s?” he asks an ordinary man during a robbery. Since it’s the man’s personal money, Clyde says gallantly, “Keep It.”

But Clyde is not a Robin Hood” type, as the banks he robs are small-town savings-and-lawn affairs (where many working class people did keep the little money they had. The movie creates the false illusion that they rob banks as if they are impersonal institutions.

Deadly Finale

Nonetheless, the most significant question raised by the movie was the specific manner in which Penn shot and edited the big finale, depicting the ambush of Bonnie and Clyde by police officers. The sequence was shot as a montage, alternating slow-motion shots with normal depictions of time, repeating certain images from various camera angles, thus prolonging what would have been a ten or twelve-second sequence (if realistically portrayed) into a two-minute “ballet of blood,” as one critic put it.

In the original script, the deaths take place off screen. However, Penn defended his decision about the controversial ending by suggesting that Bonnie and Clyde were mythic, larger-than-life characters, and his treatment of the last scene was necessary in order to visually portray the deaths of legendary figures rather than that of two ordinary people.

Credits

Produced by Warren Beatty

Screenplay by David Newman and Robert Benton

Directed by Arthur Penn.

Cast:

Clyde Barrow (Warren Beatty)

Bonnie Parker (Faye Dunaway)

C. W. Moss (Michael J. Pollard)

Buck Barrow (Gene Hackman)

Blanche Barrow (Estelle Parsons)

Malcolm Moss (Dub Taylor)

Captain Frank Hamer (Denver Pyle)

Velma Davis (Evans Evans)

Eugene Grizzard (Gene Wilder)

Grocery Store Owner (James Stiver)