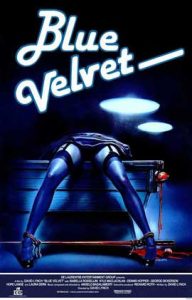

Many directors have probed the negative aspects of presumably clean and neat small town life, as represented by the symbolic white picket fences. But in Blue Velvet, arguably one of David Lynch’s two or three masterpieces, he merges all the genre’s elements and clichés into fresh insights, resulting in a rather seductively eroticized Hardy Boy reverie/nightmare of the clash between forces of good and evil.

In Blue Velvet, the small-town of Lumberstone, social time is measured by Nature. The radio station announces, “At the sound of the falling tree, it’s 9:30.” It’s the kind of town “that knows how much wood a woodchuck chucks.” The film features a brilliant beginning: the camera pans slowly across clean white-picket fence, with red roses in front of it.

It’s a beautiful day with blue skies, pleasant sounds of birds chirping and a faint sprinkler. The clean-uniformed policemen smile as they outstretch their arms and let children cross the street safely. A bright red-fire engine is moving slowly down the street; the firemen are also smiling. The whole sequence has a dreamy, surrealistic, quality. Yellow tulips sway in a warm afternoon breeze, as the sprinkler goes around shooting water. The camera suddenly cuts to under the grass and ominous sounds come up as black insects are crawling and scratching in the darkness. This powerful image sets the film’s tone, announcing its thematic concern: the dialectic duality of beautiful surfaces and the horrible things that lurk underneath.

Dressed in khaki trousers, canvas shoes, straw hat, and dark glasses, Mr. Beaumont (Jack Harvey) is watering his grass with a hose, but he is suddenly hit with a seizure and falls to the ground. The water shoots crazily onto the driveway and his car. At the same time, Mrs. Beaumont (Priscilla Pointer), is curled up on the couch, smoking a cigarette and enjoying her daytime soap. The precariousness of human life: the sudden eruption of violence, a seizure, in the most peaceful of settings, is jarring. Shortly after, Jeffrey Beaumont (Kyle MacLachlan) is called back home from college. He has to work at his father’s business, the Beaumont’s hardware store. At the hospital, the father is concerned because Jeffrey has never been seen him with his teeth out; once again, the theme of appearances versus reality.

Walking down the dirt road in a vacant field, Jeffrey finds a human ear, covered with ants racing frantically around it. A good boy, he reports the incident to detective J.D. Williams (George Dickerson) who asks Jeffrey not to discuss the incident with anyone. But understanding that Jeffrey is “real curious,” the detective says, “I was the same when I was your age, that’s what got me into this business.” The coroner says he doesn’t “recall anything coming in minus an ear,” suspecting the person might still be alive. A close-up of the ear, in a mortician’s dish, reveals a rare view of the crevices around the dark hole.

A small community, people know each other in Lumberstone. Mrs. Williams (Hope Lange) knows Jeffrey’s mother from church. Her daughter, Sandy (Laura Dern), a high school senior, remembers Jeffrey as “pretty popular” from school. All of Jeffrey’s old friends are gone (to college), and lonely, he strikes a friendship with Sandy. Sandy arouses his curiosity when she tells him about a woman who has been under surveillance. He decides to spy on her. “There are opportunities in life for gaining knowledge and experience,” says Jeffrey, and in some cases “it’s necessary to take a risk.” This provides “justification” for his proposition to sneak in and observe the mysterious woman. Still a child, Sandy thinks his idea sounds like “a good daydream,” but doing it is “too weird, too dangerous.”

Dorothy Vallens (Isabella Rossellini) is a beautiful woman with round figure and full red lips. She sings at the “Slow Club,” a sleazy nightclub on the outskirts of town, surrounded by a trash-strewn parking lot. Dorothy sings a slow version of “Blue Moon” and Bobby Vinton’s “Blue Velvet.” There is also the “Barbary Coast,” a corner bar with a back room with naked girls. Both clubs are set apart from Main Street.

Jeffrey’s sexual naivet is juxtaposed with the villain’s, Frank Booth (Dennis Hopper), a brute endowed with raw sexuality (“I’ll fuck anything that moves”). Frank has kidnapped Dorothy’s husband and son and now abuses her sexually. Stocky with a burr hair cut, Frank wears an old black jacket, blue jeans and boots. “Mommy, Baby wants to fuck,” he says while looking at Dorothy’s crotch and wearing a mask for the canister filled with helium. He sucks and bites the velvet coming out of her mouth, while pinching her breasts. Slugging her in the face, he reaches a climax in his pants. Later, Jeffrey suffers the ultimate degradation when Frank smears lipstick on his face and kisses him on the lips.

But like other small-town narratives, social order must be restored. Jeffrey’s mother says at one point, “You just can’t stay out half the night and carry on, there’s got to be some order.” The theme of unspeakable horror lurking beneath seemingly ordinary life is expressed by Sandy, “It’s a strange world,” and Jeffrey, “Why is there so much trouble in the world” Sandy recounts a dream in which “the world was dark because there weren’t any robins,” but “all of a sudden, thousands of robins flew down and brought the blinding light of love.” Indeed, like Shadow of a Doubt, the narrative reaffirms that “love would be the only thing that would make any difference,” but “until the robins come there is trouble.”

Like many small-town films, “Blue Velvet” is about coming of age, that phase of transition from adolescence to adulthood, though the rites of passage are not ordinary (as were Norman and Allison’s innocent kiss on a hill or Rodney and Betty’s swim in the nude in “Peyton Place”). Here, the sexual initiation is carried out by a mature woman, and there are no inhibitions. The film offers the shock of recognition and catharsis too, containing the most eroticized energy to be displayed on the American screen.

The film displays an innovative visual design and a complex, shifting moral tone. The images are hallucinatory, defined by a dreamy quality, but they are also realistic. For example, Lynch shows the sight of blood in close-up, and records the sound of huge cells moving. There are extreme close-ups of termites: Aunt Barbara, an absent-minded woman with thick glasses, pinches a termite and looks at it, then leaves it for Jeffrey to observe. The narrative follows the logic of a bad dream, a nightmare, dealing with the unconscious, latent and unaccountable fantasies, what may be considered in mainstream culture fevered perversity. The message is also new: through direct and actual experience, Jeffrey learns the rewards of living a clean and safe life.

The film’s worldview may be childish, perhaps intentionally so, since it is seen from an adolescent’s point of view. Jeffrey explores the dark side of his own personality. “I’m seeing something that was always hidden,” says Jeffrey, “I’m involved in a mystery, I’m learning.” The film shows both the allure of the unknown and the horror of it once encountered.

In contrast, Sandy’s adolescent status is clearer. Younger than Jeffrey, she still sees the world in black and white. “I don’t know if you’re a detective or a pervert,” she tells Jeffrey; he is actually both. Note than when a robin arrives on the kitchen window, it has an insect in its beak. Sandy represents the naive belief in a good world and decent life. The ideological distinction between Sandy and Dorothy is also visual: the blond versus the dark-haired look.

Like most small-town films of the decade, “Blue Velvet” lacks a strong or discernible moral center. Drug dealers run the town, and the police are also implicated. Detective Gordon is involved in crime, and it’s not clear how much Sandy’s father knows or is involved. “It’s over now,” detective Williams tells Jeffrey, but unlike films of previous decades, the viewers are not certain that the crime and corruption are resolved.

At the film’s coda, the narrative shifts back from the subconscious to the conscious, and from below to above ground, stressing the need for ordinary life, i.e. normal love and sex. The restoration of order and the relegation of Dorothy to normal motherhood (in the last scene, she is seen with her son) are at best precarious, if not fragile.

Oscar Alert

David Lynch received his second Best Director Oscar nomination, competing against Oliver Stone, who won for the Vietnam combat film “Platoon” (which also won Best Picture), Woody Allen for the serio comedy “Hannah and Her Sisters,” James Ivory for the literary adaptation “Room With a View,” and Roland Jaffe for “The Mission.”

Cast

Jeffrey Beaumont (Kyle MacLachlan)

Dorothy Valens (Isabella Rossellini)

Frank Booth (Dennis Hopper)

Sandy Williams (Laura Dern)

Mrs. Williams (Hope Lange)

Ben (Dean Stockwell)

Detective Williams (George Dickerson)

Mrs. Beaumont (Priscilla Pointer)

Aunt Barbara (Frances Bay)

Mr. Beaumont (Jack Harvey)

Credits

DEG (Dino De Laurentiss Entertainment Group)

Produced vt Fred Caruso

Directed, written by David Lynch

Camera: Frederick Elmes

Editor: Duwayne Dunham

Music: Angelo Badalamenti

Production design: Patricia Norris

Costume design: Gloria Laughride

F/X: Greg Hull, George Hill

Running time: 120 Minutes